U.S. LNG

Remapping Energy Security

In 2022, energy flows and trade shifted dramatically. Europe, already deep into an energy crisis, fell deeper following Russia’s February invasion of Ukraine. Russia decreased its supply of natural gas to Europe, hoping economic pain would break European and transatlantic resolve to support Ukraine.

In response, Europe hastened its plans for energy efficiency, doubled down on renewable power, and turned to global markets for gas. Gas is critical for power and heating in European winter; to prepare, Europe rushed to fill storage via conservation measures and shifting to non-Russian gas supplies, mostly from the United States.

These events have been costly. The resulting gas shortage has been expensive for Europe and destructive in emerging markets. Further, implications for the climate are still unknown. New gas infrastructure creates climate challenges if done poorly, and developing markets may lock in higher-emission energy alternatives for the long term if gas prices remain high.

Energy security in Europe—and globally—now rests on U.S. natural gas exports. Europe’s shift from Russian gas to other supplies has dramatically and permanently changed global gas trade and energy markets.

With storage full for this winter, policymakers must now prepare for years of energy restructuring. Cooperation between the United States and Europe is and will remain critical for European energy security, hastening the energy transition, and maintaining strong transatlantic trade.

For decades, the flow of natural gas from Russia into Europe was thought to be reliable. During the Cold War, gas was an instrument of peaceful exchange at a time of grave geopolitical tension. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the gas trade was key to Russia’s economic integration with the West. It was also a tenet of Europe’s security strategy, stabilizing Russia with export revenue and creating economic co-dependence.

By 2022, Europe and Russia were linked by six gas pipelines, including the controversial Nord Streams 1 and 2. Russian pipelines supplied over 40 percent of Europe’s natural gas, delivering 140-170 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year. Even as Europe prepared for a transition to zero-carbon energy, the bridge to a net-zero future would be held up by Russian gas.

In fall 2021, pipeline flows from Russia into Europe began to slow. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, gas deliveries continued to fall. Germany refused to license Nord Stream 2; Gazprom cut flows through Nord Stream 1 to record lows. Following sabotage in September 2022, flows through Nord Stream 1 ceased entirely. Gas imports from Russia into Europe are now a quarter of what they were previously, and gas supply has become a geopolitical weapon.

In 2022, energy flows and trade shifted dramatically. Europe, already deep into an energy crisis, fell deeper following Russia’s February invasion of Ukraine. Russia decreased its supply of natural gas to Europe, hoping economic pain would break European and transatlantic resolve to support Ukraine.

In response, Europe hastened its plans for energy efficiency, doubled down on renewable power, and turned to global markets for gas. Gas is critical for power and heating in European winter; to prepare, Europe rushed to fill storage via conservation measures and shifting to non-Russian gas supplies, mostly from the United States.

These events have been costly. The resulting gas shortage has been expensive for Europe and destructive in emerging markets. Further, implications for the climate are still unknown. New gas infrastructure creates climate challenges if done poorly, and developing markets may lock in higher-emission energy alternatives for the long term if gas prices remain high.

Energy security in Europe—and globally—now rests on U.S. natural gas exports. Europe’s shift from Russian gas to other supplies has dramatically and permanently changed global gas trade and energy markets.

With storage full for this winter, policymakers must now prepare for years of energy restructuring. Cooperation between the United States and Europe is and will remain critical for European energy security, hastening the energy transition, and maintaining strong transatlantic trade.

For decades, the flow of natural gas from Russia into Europe was thought to be reliable. During the Cold War, gas was an instrument of peaceful exchange at a time of grave geopolitical tension. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the gas trade was key to Russia’s economic integration with the West. It was also a tenet of Europe’s security strategy, stabilizing Russia with export revenue and creating economic co-dependence.

By 2022, Europe and Russia were linked by six gas pipelines, including the controversial Nord Streams 1 and 2. Russian pipelines supplied over 40 percent of Europe’s natural gas, delivering 140-170 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year. Even as Europe prepared for a transition to zero-carbon energy, the bridge to a net-zero future would be held up by Russian gas.

In fall 2021, pipeline flows from Russia into Europe began to slow. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, gas deliveries continued to fall. Germany refused to license Nord Stream 2; Gazprom cut flows through Nord Stream 1 to record lows. Following sabotage in September 2022, flows through Nord Stream 1 ceased entirely. Gas imports from Russia into Europe are now a quarter of what they were previously, and gas supply has become a geopolitical weapon.

U.S. LNG to the Rescue

To fill the gap left by Russian gas supplies, Europe turned to imports of U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG). Other mitigation strategies such as gas demand reduction and fuel-switching to coal or renewables compensated for Russian gas cuts, but U.S. LNG filled most of the gap. As of December 2022, U.S. LNG exports bound for Europe and the United Kingdom have increased to more than 42 percent of total LNG imports into Europe.

Faced with potential shortages, European countries paid high prices to secure gas. U.S. LNG was uniquely suited to respond to higher prices, because most U.S. LNG contracts allow buyers to resell cargoes or divert ships to the highest paying customers. Many Asian buyers, especially China, resold LNG to Europe for profit.

European gas prices acted as a magnet for LNG. So far in 2022, European gas prices averaged $41 per million British thermal units (mmbtu), double the $18/mmbtu price in Japan and six times the $6.5/mmbtu paid in the United States. Such high prices secured supplies for Europe but also drove up costs for households and businesses.

U.S. LNG has become the second-largest source of gas imports to Europe, after pipeline gas from Norway, following accelerated Russian pipeline cuts over the summer. U.S. LNG supplied 17 percent of total European gas imports in 2022 at a time when Russia met 19 percent of European gas imports. Other nations—including Norway, Azerbaijan, and Qatar—have stepped up their exports to Europe, collectively adding 28 bcm in 2022. But the United States added 37 bcm, more than all other LNG sources combined.

Energy Diplomacy

In March 2022, the Biden administration and the European Commission agreed to expand U.S.-EU gas trade by at least 50 bcm per year by 2030. The United States began with an additional 15 bcm in 2022, a target met by September 2022. Market dynamics still determine infrastructure investment on the American side. However, the Biden administration’s commitment should quell fears that U.S. policymakers will curb exports to curb domestic natural gas prices or for climate reasons.

In November, a renewed EU-U.S. agreement for energy security implies that Europe will seek up to 147 bcm of LNG imports in 2023. Though this target is roughly double the lost Russian pipeline supply (77 bcm in 2022), Europe exceeded it in 2022 with 159 bcm of LNG imports. Governments in Europe are acting quickly to increase import capacity.

European power firms have secured contracts for 11 floating storage regasification units (FSRU), adding more than 55 bcm per year of regasification capacity to the continent by the end of 2023. This expansion was driven by subsidies to utilities, government procurement (four were purchased by the German government), and accelerated permitting.

Europe’s energy mix will emerge from this crisis more diversified than ever, with new sources of imports, points of entry, delivery routes, and types of energy.

New import capacity and pipeline expansions will restructure the European gas market, adding connectivity between countries previously dependent on a single source. Much of this infrastructure is being built ready to transition to biogas or hydrogen. Europe’s energy mix will emerge from this crisis more diversified than ever, with new sources of imports, points of entry, delivery routes, and types of energy.

Policy Challenge: Limiting Economic Impacts

Economic recession in Europe is likely due to high energy prices, combined with rising inflation and interest rates. Parts of the European industry have stopped producing, as most gas-intensive industries can not afford the price of fuel. Production of nitrogen-based fertilizer in Europe has slowed by 70 percent. Overall, European industrial gas demand is down by around 40 percent year over year.

Securing public support from Europe and the United States for the war in Ukraine and its economic sacrifices could become more challenging if economic hardships worsen. European and American taxpayers are not ready to pay endlessly for the war, Ukraine’s reconstruction, and growing energy bills.

In Europe, governments are looking to control costs with price caps on gas imports and rationing short supplies between countries and particular sectors. Government interventions should avoid dissuading firms from adding to supply and increasing total U.S. exports. On the U.S. side, understanding the burden of high energy costs in Europe and working with European partners to control these costs will be crucial in maintaining the flow of LNG exports.

In March 2022, the Biden administration and the European Commission agreed to expand U.S.-EU gas trade by at least 50 bcm per year by 2030. The United States began with an additional 15 bcm in 2022, a target met by September 2022. Market dynamics still determine infrastructure investment on the American side. However, the Biden administration’s commitment should quell fears that U.S. policymakers will curb exports to curb domestic natural gas prices or for climate reasons.

In November, a renewed EU-U.S. agreement for energy security implies that Europe will seek up to 147 bcm of LNG imports in 2023. Though this target is roughly double the lost Russian pipeline supply (77 bcm in 2022), Europe exceeded it in 2022 with 159 bcm of LNG imports.

European power firms have secured contracts for 11 floating storage regasification units (FSRU), adding more than 55 bcm per year of regasification capacity to the continent by the end of 2023. This expansion was driven by subsidies to utilities, government procurement (four were purchased by the German government), and accelerated permitting.

Europe’s energy mix will emerge from this crisis more diversified than ever, with new sources of imports, points of entry, delivery routes, and types of energy.

New import capacity and pipeline expansions will restructure the European gas market, adding connectivity between countries previously dependent on a single source. Much of this infrastructure is being built ready to transition to biogas or hydrogen. Europe’s energy mix will emerge from this crisis more diversified than ever, with new sources of imports, points of entry, delivery routes, and types of energy.

Policy Challenge: Limiting Economic Impacts

Economic recession in Europe is likely due to high energy prices, combined with rising inflation and interest rates. Parts of the European industry have stopped producing, as most gas-intensive industries can not afford the price of fuel. Production of nitrogen-based fertilizer in Europe has slowed by 70 percent. Overall, European industrial gas demand is down by around 40 percent year over year.

Securing public support from Europe and the United States for the war in Ukraine and its economic sacrifices could become more challenging if economic hardships worsen. European and American taxpayers are not ready to pay endlessly for the war, Ukraine’s reconstruction, and growing energy bills.

In Europe, governments are looking to control costs with price caps on gas imports and rationing short supplies between countries and particular sectors. Government interventions should avoid dissuading firms from adding to supply and increasing total U.S. exports. On the U.S. side, understanding the burden of high energy costs in Europe and working with European partners to control these costs will be crucial in maintaining the flow of LNG exports.

Supply Concerns

Will Boost Investments

Global export capacity for LNG is limited. Because of this, Europe’s purchases of large volumes of gas have increased prices and diverted cargoes away from other regions. Increased global prices and fear of global supply shortage will drive construction of new export capacity in the United States.

Before natural gas can be exported and shipped across seas, it is processed through liquefaction plants, where it is cooled to a temperature below −260°F (160.5°C) and loaded onto ships.

Currently, the United States has seven large-scale liquefaction plants in operation, concentrated along the Gulf coastlines of Texas and Louisiana. Strong demand for U.S. LNG means these facilities are being run close to or above maximum capacity.

Policy Challenge: Infrastructure Disruptions

With limited export capacity globally, a failure in U.S. gas infrastructure can have significant impacts for global supply and prices. The 2022 Freeport LNG fire removed nearly 17 percent of U.S. LNG exports and has yet to be repaired.

With facilities running near full capacity, equipment failures and staffing shortages will be persistent threats to supply. The concentration of U.S. export facilities on the Gulf Coast means that hurricanes and ship congestion pose threats to operations and delivery times. Sabotage and cyber attacks will also remain threats.

Infrastructure owners will have to continually invest in cyber security. As export capacity is added, it will provide a buffer against failure-induced shortages. Firms might choose to spread to more diverse locations, with potential projects in Alaska and on the Pacific Coast.

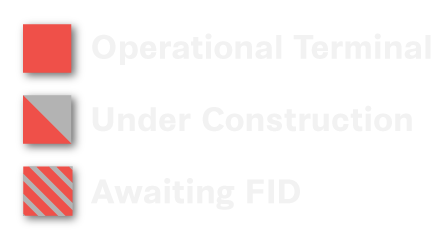

Enough export terminals have been approved by the U.S. government for construction to double U.S. export capacity. Some of those facilities are still awaiting final investment decisions (FIDs).

These decisions are made when a facility has enough contracted buyers and financing to secure investment. Two FIDs were already been made in 2022. Increased demand will likely allow for one or two additional FIDs for a large-scale greenfield project over in 2023.

With additional investment, the United States could remain the world’s largest holder of LNG export capacity within the decade. Under planned expansions, the United States will increase its export capacity by 17 percent by the end of 2025 and will increase further by 43 percent before 2028, surpassing both Australia and Qatar.

Recent deals between U.S. LNG exporters and Chinese entities (state-owned, regional, private) are giving Beijing significant clout in pricing and market share. Before the European crisis, China was on track to become the largest importer of U.S. LNG in 2022. Both the Covid-19 response and high global prices reduced China’s demand for LNG.

In 2022, Europe benefited from reduced Asian LNG appetite. Now, China is working to restart its economy and could start to keep LNG imports for itself. Europe will have little recourse if China decides to use more LNG. Chinese control of long-term import contracts creates supply risks for European imports of LNG and demand uncertainty for U.S. exporters.

Energy Transition

and the Last Gas Boom

Whether growing gas supply will exacerbate climate change depends on the amount of gas produced, the emissions of the LNG system, and how the gas is used.

The relationship between expanding LNG supply capacity and the transition to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions is complicated. Replacing lost Russian supply with new U.S. LNG capacity will have minimal effect on global emissions, as Russia cannot divert gas to other markets in large quantities. But as Russia fills its gas storage, new production could make pollution worse, as unwanted surplus gas would be openly burned or leaked.

European governments are wary of overcommitting to gas infrastructure. Gas demand in Europe is set to fall as countries move toward emissions-free energy, a trajectory the European Union does not want to jeopardize. European policymakers do not want gas buyers locked into 15- or 20-year contracts, which would challenge EU climate commitments. This hesitancy could prevent enough capacity expansion to secure gas supplies this decade.

Policy Challenge: Greening U.S. LNG

Regulating the emissions of U.S. LNG will remain a priority for both political acceptance and emissions reductions, particularly as the LNG market grows. U.S. suppliers and exporters are putting more emphasis on greening their operations by reducing emissions.

The Inflation Reduction Act provides support for powering liquefaction facilities with renewables; using carbon capture to prevent emissions; and monitoring, reporting, and verifying emissions throughout the LNG value chain. Through firm regulations on methane emissions and diplomatic cooperation with the European Union, the United States can limit the climate impacts of expanding gas infrastructure to meet energy security needs.

The market shift toward Europe has also increased global prices for LNG and caused supply shortages in emerging markets such as Pakistan and Bangladesh. A prolonged period of high prices could slow the switch from coal- or oil-fired power generation to gas in emerging markets, locking in more emissions as countries rethink their future energy mixes.

LNG imports are currently concentrated in a select pool of wealthy nations: just eight LNG importers have absorbed 74 percent of global LNG trade. U.S. exports were shipped to 36 different countries in 2022, but Europe absorbed the lion’s share of U.S. LNG (64 percent).

Countries that had planned to replace coal power with natural gas imports have slowed or changed their plans. The Philippines pushed the first planned LNG imports from 2022 to the end of 2023, while progress on Vietnam’s proposed LNG-to-power terminals project is extremely slow. The role of LNG as an affordable, secure, and cleaner alternative to coal is in question in emerging markets.

Some emerging countries will remain relevant to global LNG trade, especially if gas infrastructure already exists and long-term contracts are in place, as is the case for India. Long-term contracts, which can expand supply, will be important provided those contracts are flexible to changing market conditions and countries’ net-zero paths.

A Bright Future

for Transatlantic Ties

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will have a lasting and transformative impact on energy geopolitics. Countries are designing economic relationships to support and work with aligned countries. A foundation of common support for liberal democracy and global order rests under the transatlantic relationship.

For the United States and Europe, expanding energy trade could easily evolve into deeper strategic cooperation around climate and energy. Both Europe and the United States are interested in clean hydrogen, carbon capture and sequestration, methane reductions, geothermal energy, offshore wind, and other clean technologies.

The infrastructure of LNG trade can be leveraged for decarbonization. The United States and Europe could facilitate the shipping industry’s transition to net-zero emissions by leveraging existing and future LNG infrastructure to deal with a variety of cleaner fuels.

Even the infrastructure of LNG trade can be leveraged for decarbonization. The United States and Europe could facilitate the shipping industry’s transition to net-zero emissions by leveraging existing and future LNG infrastructure to deal with a variety of cleaner fuels. Public-private partnerships in Europe and the United States could link ports on both sides of the Atlantic to showcase the decarbonization of shipping itself. This long-term energy and climate partnership will also reinforce transatlantic cooperation in securing supply chains.

Partnerships in cleaner technology could be deepened through technology transfers, know-how sharing, and new trade rules. Trade tensions, like those created by the domestic subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act, could be ameliorated by the success and example of the LNG trade. Leveraging U.S. LNG to deliver lowest-emissions gas, clean hydrogen, and zero-emissions shipping will be key to maintaining momentum in the transatlantic energy trade and securing a clean energy system.

Conclusion

Europe’s shift to U.S. LNG has created a qualitatively different map of energy security in the wake of Russia’s invasion. Europe now relies on U.S. imports of natural gas to heat homes, power its grid, and fuel its industry. This new trade should bolster the transatlantic relationship in a time of increasing geopolitical tension.

The changes in gas flows around the world have been costly. Energy prices in Europe are threatening recession and closing manufacturing facilities. High costs have trickled down to emerging markets and caused real crises.

Just seven years ago, the United States exported almost no LNG. Now, as Europe and the world increasingly rely on U.S. gas exports, the United States must establish its own strategy for gas.

Policymakers will have to manage these costs through market reforms, energy efficiency, and adding to global gas capacity. To add capacity, policymakers will need to require new infrastructure be as clean as possible and create conditions for gas to displace coal.

Just seven years ago, the United States exported almost no LNG. Now, as Europe and the world increasingly rely on U.S. gas exports, the United States must establish its own strategy for gas.

Many questions for U.S. policymakers remain: How will LNG export demand be balanced with domestic consumption of gas? How will political leadership capitalize on the economic and geopolitical benefits of LNG exports? How will domestic environmental regulations, infrastructure, and permitting decisions affect the U.S. response to this crisis?

Answers to these questions will help Europe understand the strength of the transatlantic energy partnership and set the course for the next two decades of energy.

This report is funded by general support to CSIS. No direct sponsorship contributed to this report.

Europe’s shift to U.S. LNG has created a qualitatively different map of energy security in the wake of Russia’s invasion. Europe now relies on U.S. imports of natural gas to heat homes, power its grid, and fuel its industry. This new trade should bolster the transatlantic relationship in a time of increasing geopolitical tension.

The changes in gas flows around the world have been costly. Energy prices in Europe are threatening recession and closing manufacturing facilities. High costs have trickled down to emerging markets and caused real crises.

Just seven years ago, the United States exported almost no LNG. Now, as Europe and the world increasingly rely on U.S. gas exports, the United States must establish its own strategy for gas.

Policymakers will have to manage these costs through market reforms, energy efficiency, and adding to global gas capacity. To add capacity, policymakers will need to require new infrastructure be as clean as possible and create conditions for gas to displace coal.

Just seven years ago, the United States exported almost no LNG. Now, as Europe and the world increasingly rely on U.S. gas exports, the United States must establish its own strategy for gas.

Many questions for U.S. policymakers remain: How will LNG export demand be balanced with domestic consumption of gas? How will political leadership capitalize on the economic and geopolitical benefits of LNG exports? How will domestic environmental regulations, infrastructure, and permitting decisions affect the U.S. response to this crisis?

Answers to these questions will help Europe understand the strength of the transatlantic energy partnership and set the course for the next two decades of energy.

This report is funded by general support to CSIS. No direct sponsorship contributed to this report.

Authors

Special thanks to Ian Barlow for writing, content, and project support.

Story Production by

CSIS iDeas Lab

- Production, management, design, and maps by Michael Kohler

- Development and data visualizations by Lindsey Urchyk

- Copyediting support by Katherine Stark

- Project and content oversight by Sarah Grace

Sources

- Photos: Calcasieu LNG Terminal | FRANCOIS PICARD/AFP via Getty Images (Header Photo); Golden Pass LNG Terminal | Carol M. Highsmith via Library of Congress (Supply Concerns Will Boost Investments); NASA Earth Observatory (Conclusion); Adobe Stock; Storyblocks

- Numerical and time series data: Dror Guzman/Gas Vista via Leviaton Ai

- Map: © Mapbox, © OpenStreetMap, Gas Vista