Ukraine's Potential Energy

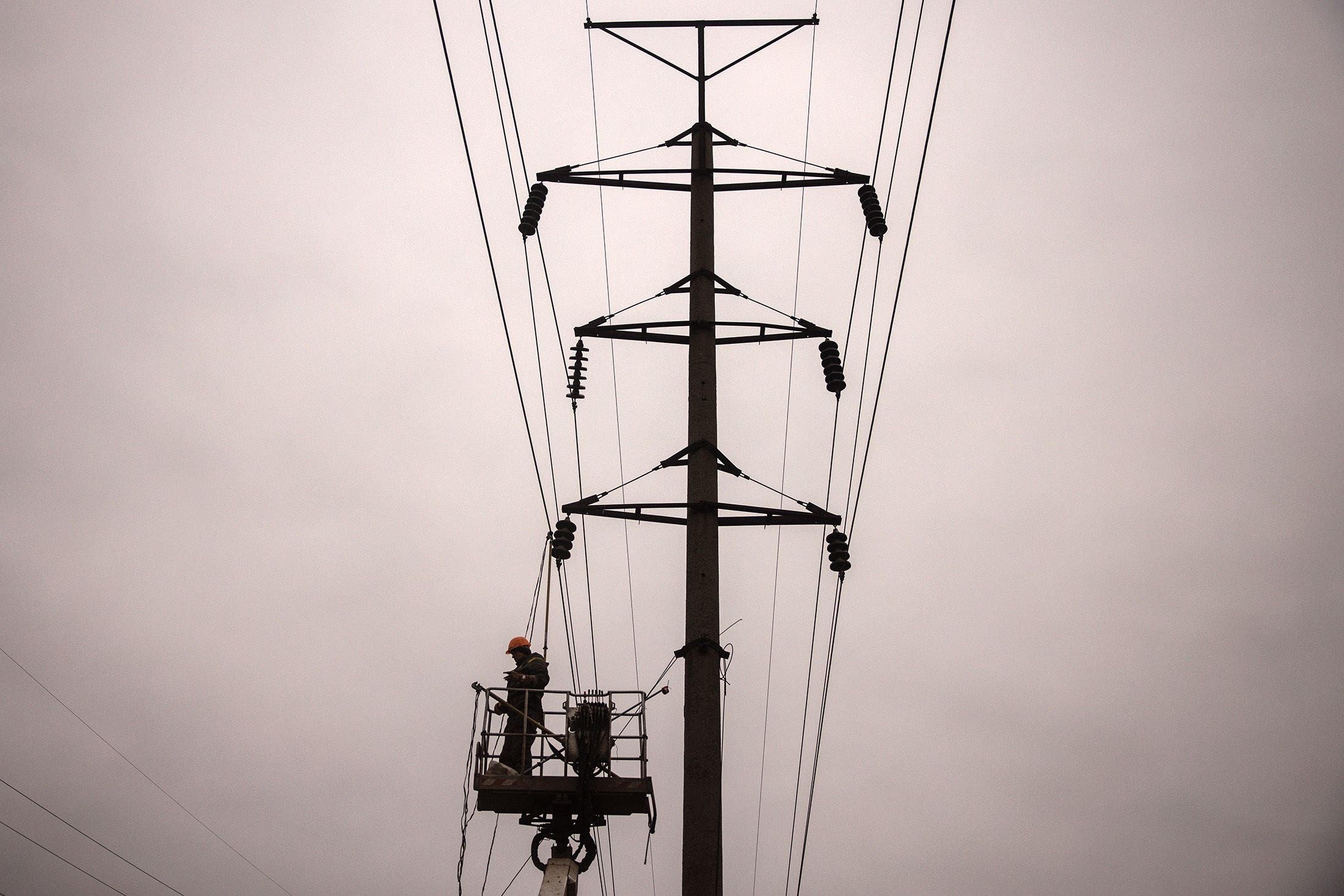

Russian attacks have devastated Ukraine's electrical grid. How it rebuilds may not just determine the future resilience of its grid, but its relationship with Europe.

On October 10, 2022, Russian missiles struck critical power substations in Ukraine, cutting the lights in major cities across the country. Such attacks, once viewed as improbable and contrary to Putin’s goal of occupation or regime change, have become routine for millions of Ukrainians.

This attack marked the beginning of a new era of the war in Ukraine. While it began with volleys of missiles falling on civilian areas, the summer primarily saw conflict outside major urban centers, with both sides focusing on controlling territory. With successful Ukrainian military offensives and the bombing of the Kerch bridge in Crimea, pressure mounted in Russia for retaliatory action. The Kremlin responded by targeting critical civilian infrastructure.

Infrastructure Under Attack

Ukraine’s power grid is uniquely susceptible to these attacks. Ben Cahill, a senior fellow with the Energy Security and Climate Change Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), noted that Russia “knew the most vulnerable parts of the Ukrainian energy system and attacked those mercilessly.” Russia was aware of these weaknesses because of a fatal historical quirk: they were built by the USSR, and Russia has assisted in their maintenance for decades.

The composition of Ukraine’s energy grid only exacerbated this vulnerability.

In 2017, four nuclear power plants provided just under 25 percent of the nation’s energy. Ukraine’s dependence on a handful of power plants made it straightforward for Russia to target critical power infrastructure through missile and drone strikes, according to Allegra Dawes, a research associate at CSIS’s Energy Security and Climate Change Program.

“One of the challenges for Ukraine is that the nuclear power sector has played such a big role in electricity generation, and these are Soviet built reactors.”

Ukraine had reason to expect that Russia might target its power system. Max Bergmann, the director of the Eurasia Program at CSIS, notes that "there’s been a lot of precedent, at least in terms of Russia’s hybrid capabilities over the last 20 years, where Russia has targeted civilian infrastructure, often through cyber means, through attacking power grids."

A Russian hacking group called Sandworm first came to global attention when it attacked a Ukrainian media company in 2015. These attacks escalated at the end of that year when Sandwormtargeted the Prykarpattyaoblenergo power company, which caused widespread blackouts in Eastern Ukraine.

In Syria, the Kremlin expanded the scope and intensity of its attacks on civilian infrastructure, using artillery to attack schools, hospitals, power plants, and other non-military facilities in 2019. As a result of these hyper-visible attacks, and increasing Russian aggression with the annexation of Crimea, Ukraine began to evaluate the weaknesses in its own infrastructure systems.

Ukraine’s power grid, which was largely constructed during the Soviet era, was directly connected to a larger grid that included Russia and Belarus. As security concerns grew about an increasingly belligerent Russia, Ukraine drafted plans to develop a more independent grid in 2013. While the initial pace of separation had been slow, mounting threats intensified the pace at which the Ukrainian government worked to secure its grid.

On the eve of Russia’s invasion, Ukraine had planned to disconnect from Russia’s grid for 72 hours. This was meant to be a brief test run before reconnecting to Russian power, as Ukraine’s grid did not have the capacity to run independently for long. The reconnection never happened; four hours after the supply of power was cut off, Russian tanks began rolling over the border.

Closed shops in Maaret al-Numan in Syria's southern Idlib governorate are shown in December 2022. | Omar Haj Kadour / AFP via Getty Images

Closed shops in Maaret al-Numan in Syria's southern Idlib governorate are shown in December 2022. | Omar Haj Kadour / AFP via Getty Images

Russia Changes Strategy

Since the first days of the war, Russian forces have targeted Ukrainian energy infrastructure. But in the initial phase of the conflict, Russia sought to control, not destroy, Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, as Russia presumed it would be quickly victorious and occupy the country. On March 4, 2022, it captured the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, the largest nuclear facility in Europe. With a single battle, it had eliminated nearly 10.7 percent of Ukraine’s total energy production.

A few weeks later, Russia tried connecting Zaporizhzhia to their own country’s grid. Its engineers, however, struggled to divert the power. Although they were familiar with the Soviet systems, they could not bypass the Western safety technology that Ukraine had installed over the previous few decades. By the time the engineers coerced Ukrainian workers to explain the system, Ukrainian forces had blown up a crucial substation in Crimea, sinking the plan entirely.

Despite the trouble at Zaporizhzhia, Russian forces planned to capture other plants. In July, they took the coal-fueled Vuhlehirsk plant, Ukraine’s second-largest energy facility. Although Ukraine reclaimed large chunks of territory in early autumn, Vuhlehirsk still sits in Russian-controlled territory.

Energy Terrorism

At the outset of the war, Russia expected a quick victory in Ukraine. It would charge Kyiv, topple the Zelensky government, and install a new, pro-Russian leader. When Ukraine resisted longer than expected, it resorted to scorched-earth tactics. In early October, Russia changed its strategy—instead of diverting Ukrainian energy, it would destroy it.

According to Bergmann, in the first stage of the war, Russian forces “wanted the infrastructure to remain in place because they didn’t want to have to spend their own resources to rebuild it.” As they lost ground in the summer, they started “to destroy Ukraine, trying to destroy the civilian infrastructure, because they know they can’t take it.”

Russia adopted a strategy of energy terrorism. If it could not win the war on the battlefield, perhaps it could win by ruining the morale on the Ukrainian home front. Russian officials have stated that civilian suffering is the explicit point of these attacks. Russian MP Boris Chernyshov, for example, hopes that Ukrainians “freeze or rot.”

Through the first three weeks of October, Russia destroyed power plants in 16 of Ukraine’s 24 regions, damaging nearly half of the country’s energy infrastructure. Blackouts afflicted Kyiv, Lviv, and many other cities. In the last days of October, Russia began a second wave of drone strikes, and an attack on November 23 disrupted power for millions and caused a week-long blackout in some places.

That attack also forced Ukraine to disconnect its four operational nuclear plants from the national energy grid, which increased the danger of a nuclear disaster. To run its cooling system, a nuclear plant needs to draw energy from another facility. If its external power source is severed for too long, the plant could melt down—a similar meltdown caused the Fukushima disaster in 2011. Some experts worry that if Russian forces destroy the facilities that power the reactors, radioactive material could contaminate much of Ukraine.

People rest in a coffee shop in Lviv as the city lives through a scheduled power outages after Russian airstrikes on the Ukrainian energy infrastructure. | Yuriy Dyachyshyn / AFP via Getty Images

People rest in a coffee shop in Lviv as the city lives through a scheduled power outages after Russian airstrikes on the Ukrainian energy infrastructure. | Yuriy Dyachyshyn / AFP via Getty Images

Featuring interviews from Ukrainian citizens Roman and Vlad.

Background Music via Artlist.io - In This Together by Lance Conrad; Dawn Drift by Doug Kaufman

Because of Russian energy terrorism, Ukrainians suffer from a perpetual energy shortage. According to Dawes, Ukraine’s grid operator uses rolling outages to protect the country’s intact facilities, disrupting the lives of millions of civilians. Although the country has benefited from a mild winter, many have struggled to stay warm.

Vulnerable Ukrainians suffer the most from these outages. Without electricity, hospitals cannot help the injured and elderly citizens who most need their services. In Kyiv, many patients suffered organ damage when their oxygen concentrators lost power. One resident recalled watching her mother, a 75-year-old cancer patient, struggling to catch her breath for hours.

Ukraine has tried to patch the holes in its grid. Replacement parts are not widely available, so engineers have improvised with imperfect parts, Cahill said. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has provided backup generators and kits with parts from U.S. utility companies—they are imperfect fits, but they help in the short term. In Kyiv, Ukrainians have set up “points of invincibility,” stations where neighbors can warm up and charge their electronics. They run on generators and are therefore not subject to rolling blackouts.

So far, Ukraine has done its best to keep energy flowing to its citizens. When the war ends, it will need to rethink and redesign how its energy infrastructure functions.

Activating Ukraine's Potential Energy

Even if the war ends with Ukraine still independent and intact—an outcome that is far from certain—Ukraine faces a herculean task in rebuilding its energy infrastructure. It must not only rebuild what has been destroyed but also strive to create a new grid that is more resilient to future threats.

From the threat of Russian cyberattacks to climate change-induced stress on the grid, Ukraine will confront challenges that require it to build back better.

On July 4, 2022, Ukraine outlined an ambitious 10-year, comprehensive National Recovery Plan at the Ukraine Recovery Conference in Lugano, Switzerland.

Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelensky appears on a giant screen as he delivers a statement at the start of a two-day International conference on reconstruction of Ukraine, in Lugano on July 4, 2022. | Fabrice Coffrini/AFP via Getty Images

Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelensky appears on a giant screen as he delivers a statement at the start of a two-day International conference on reconstruction of Ukraine, in Lugano on July 4, 2022. | Fabrice Coffrini/AFP via Getty Images

Of the plan’s estimated $750 billion, roughly $130 billion (equivalent to 65 percent of Ukraine’s GDP in 2021) is earmarked for energy reconstruction and development.

Renewable Energy

First, the plan’s energy agenda calls for Ukraine to aggressively diversify its energy mix, moving away from nuclear power toward renewables such as wind, solar, and biomass.

Ukraine is well positioned to make that shift. Before the war, the Ukrainian government had already set a goal of sourcing 25 percent of its total energy mix from renewables by 2035.

To do so, it will need to further develop its existing renewable generation in its southern and eastern regions, where solar irradiation is highest for photovoltaic generation and terrain is the flattest for wind generation. These regions—Odesa, Zaporizhzhia, Mykolaiv, Kherson, and Dnipro—accounted for around two-thirds of operating wind and solar plants prior to the war.

Much of this territory is currently held by Russian forces, and reclaiming and militarily reinforcing it will be critical to Ukraine’s renewable energy transition.

Modernizing the Grid

Second, the plan’s energy agenda calls for Ukraine to rapidly modernize its physical energy infrastructure.

This would primarily center on enhancing Ukraine’s grid-balancing capabilities and addressing its lack of storage capacity.

Grid balancing is the complicated task of ensuring that newly generated electricity precisely matches electricity demand in real time. If excesses—electricity oversupply or undersupply—are not correctly balanced, the excess voltage or power can damage system software and electronics.

Ukraine’s grid balancing involves increasing existing power-generating infrastructure to smooth out the supply of power. This often involves ramping up generation in the same Soviet-era power plants that made it initially dependent on Russia, and thus vulnerable to attack. Microgrids—siloed grids that do not rely on main interconnection—prevent initially isolated grid failure or disruption from becoming widespread.

Bolstering overall storage capacity is also vital to expanding microgrids. This is particularly true if Ukraine diversifies its energy mix with renewables as planned. Since energy production from these sources is not constant throughout the day, storage capacity is needed to bank power when generation is higher for use when generation is lower.

Challenges to the Vision

The National Recovery Plan faces significant, but not insurmountable, headwinds in realizing its vision of an energy resilient Ukraine.

The biggest hurdle is funding.

While many development banks and institutions from around the world have expressed interest in investing, the National Recovery Plan acknowledges that Ukraine needs sustained private investment to support multiyear, capital-intensive public-private projects.

Long term, the private sector’s willingness to invest the billions that the plan calls for rests on Ukraine’s ability to reform, weeding out longstanding corruption and inefficiencies in its energy sector and public sector that have previously deterred investment. The country must also cultivate a transparent market environment, creating an even playing field to facilitate external investment and domestic innovation in the energy sector.

Bergmann notes how the policy reforms Ukraine can make to attract sustained investment in its energy sector work across purposes in its goal to become a “European country” and part of the European Union.

He explains, “if you’re going to join the EU, you have to update all your laws—all your regulations. You have to get in line with European standards. You have to deal with corruption. You have to deal with a lack of transparency.”

Reforms in Ukraine will be necessary to unlock support from Europe.

"It is necessary not only to restore everything that the occupiers destroyed, but also to create a new basis for our life, for Ukraine—safe, modern, convenient, barrier-free."

Ukraine's European Future?

The National Recovery Plan’s energy agenda positions Ukraine to become a sustainable energy exporter to Europe.

This would complement the European Union’s decarbonization and energy security goals.

In this respect, the timing of the National Recovery Plan’s announcement was no coincidence, coming only a week after Ukraine officially acquired EU candidate status on June 23, 2022.

This is the latest reflection of Kiev’s continued shift to the West, which has included the ousting of Russian-backed former president Viktor Yanukovych and the subsequent signing of an EU Association Agreement back in 2014.

As Ukraine turns West, it must remain receptive to the change that will come as it forges its own path.

Conclusion

If Ukraine prevails against Russia, it has an opportunity to turn devastation into opportunity.

It can transform its energy grid, which has been a great vulnerability during the war with Russia, into one of its biggest assets. It has the ability to become a green technology exporter to Europe, lead the continent in renewable generation, and secure a more energy resilient future. But it must make the necessary reforms to attract the investment that will be needed to jumpstart growth and innovation in its domestic energy industry.

The easiest route for it to overcome this hurdle is European integration. The very same reforms that will help Ukraine gain entry into the European Union—anti-corruption measures, transparent corporate governance policies, and consistent regulatory frameworks—will also help it to secure greater private investment from across the globe.

In this respect, Ukraine’s path to energy security goes through Europe.

Authors

Video Team

Ellie is finishing her bachelor's degree in government and environmental policy at Colby College in Waterville, Maine. She is involved on campus in various leadership positions, including in Colby's Student Government Association and with Colby Votes, a nonpartisan group that helps register students to vote and increase civic engagement on campus. She recently completed a thesis on offshore wind development in the Gulf of Maine and she hopes to continue her research at the graduate level. She is interested in environmental policy and the role of journalism and media in creating climate solutions and engaging stakeholders.

Video Team

Kevin is a history and Spanish double major at Colby College. At Colby, Craig is a student leader through Hall Staff as an area residence director and the president of Colby’s queer society. Kevin is deeply interested in the intersection of media and politics with experiences at the ABC affiliate in Portland, ME, the D.C. Office of CA-52, and the District Office of ME-01. Through these experiences, Craig has written news articles and press releases; monitored media engagement; arranged and held interviews, and conducted casework on the behalf of constituents. Craig is both an Emma Bowen Fellow and a QuestBridge Scholar.

Story and Web Team

Serena Klebba is pursuing a bachelor's degree in government with minors in women's studies and economics from Colby College. She is an active member of the local political community, having worked as a field organizer in Maine's second congressional district during the 2022 election cycle. She is also heavily involved in the government department at Colby, where she is an editor for the school's Overture Journal for International affairs, a member of the Goldfarb public affairs club, and has assisted with the hosting of an international conference on the work of Václav Havel.

Story and Web Team

Aaron is pursuing a bachelor's degree with a double major in government and history with a minor in East Asian studies. Aaron currently serves as the inaugural Writing Fellows program coordinator for the Colby College Farnham Writers Center. Mills also currently serves as a pedagogical partner and learning assistant for undergraduate international relations, and as an editor for student-run International Relations Journal.

Audio Team

Cristina is pursuing a bachelor's degree in government and philosophy at Colby College. Originally born in Moldova, a country in Eastern Europe, Panaguta graduated from Lester B. Pearson United World College of the Pacific, where she cultivated her global mindedness. Committed to promoting and participating in international and intercultural understanding, she aims to contribute to the accession of Moldova to the European Union and to study the relations between her country and Russia in depth.

Data Team

Hannah is pursuing a bachelor's degree in government and Spanish, with a minor in anthropology at Colby College. She is a member of the field hockey team, Colby Democrats, and fashion club, and she enjoys studying American history and politics. She can be found most of the time in the social sciences building on campus, doing research with professors and writing her own papers. She was president of student government in high school and worked on Joe Biden and Sara Gideon's campaign and has continued to work on campaigns in college.

Audio Team

Lily Peterson is a student at Colby College pursuing a bachelor's degree in sociology and currently minors in creative writing with a focus on creative non-fiction writing. She works as an intern for Colby College's admissions office and has worked as an intern for a non-profit, "Every Mom Chicago," which provides resources to new and expecting mothers in underserved communities around Chicago. She has had consistent interests in urban development and allocations of recourse across the Chicago area and how it systematically affects different communities.

Story and Web Team

Matthew Rocha is pursuing a bachelor's degree in history at Colby College. He has spent four years on the staff of The Colby Echo, of which he is a co-editor-in-chief during his senior year. He has published an essay on the Nuremberg Trials and international law in an undergraduate research journal. He has a wide array of interests, ranging from local history to astrophysics, from poetry to creative nonfiction.

Data Team

Madeleine Silano is pursuing a bachelor's degree in government and economics with a minor in French at Colby College. At Colby she is a research assistant in the government department, an economics learning assistant, and an intern in the admissions office. Last summer Silano worked as a communications intern for Maine People’s Alliance doing data analysis, graphic design, and member outreach. She is interested in working in political journalism, foreign policy, or on a congressional campaign.

Video Team

Mackenzie Younker is pursuing a bachelor's degree in government and religious studies at Colby College in Waterville, Maine. She is on the Colby women's crew and basketball varsity teams and works at the Colby Art Museum front desk. This past summer, she was an intern for a tech company in Dublin, Ireland, and her other intern experience includes working for SandCapital and Grand Junction Economic Partnerships.

Special Thanks:

- The Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF)

- Professor Aaron Hanlon, Colby College

- CSIS iDeas Lab team mentors/staff: Mark Donaldson, Cera Baker, Michael Kohler, Jaehyun Han, and Sarah Grace

- CSIS AILA staff: Julieze Benjamin, Nina Tarr, Erin Delany, and Donatienne Ruy