Trapped in Transit

Migration Chokepoints in the

Central Mediterranean

Thousands of people are stuck between Tunisia and Italy within a migration system designed to hold them back. How do current policies affect migrants, and what can regional actors change to promote the region’s sustainability?

Why Do Chokepoints Exist?

On September 30, 2024, a boat full of migrants capsized off the coast of Djerba island in Tunisia. Fifteen Tunisians, including three children, drowned. The Tunisian National Guard was alerted of the shipwreck by migrants who managed to swim ashore.

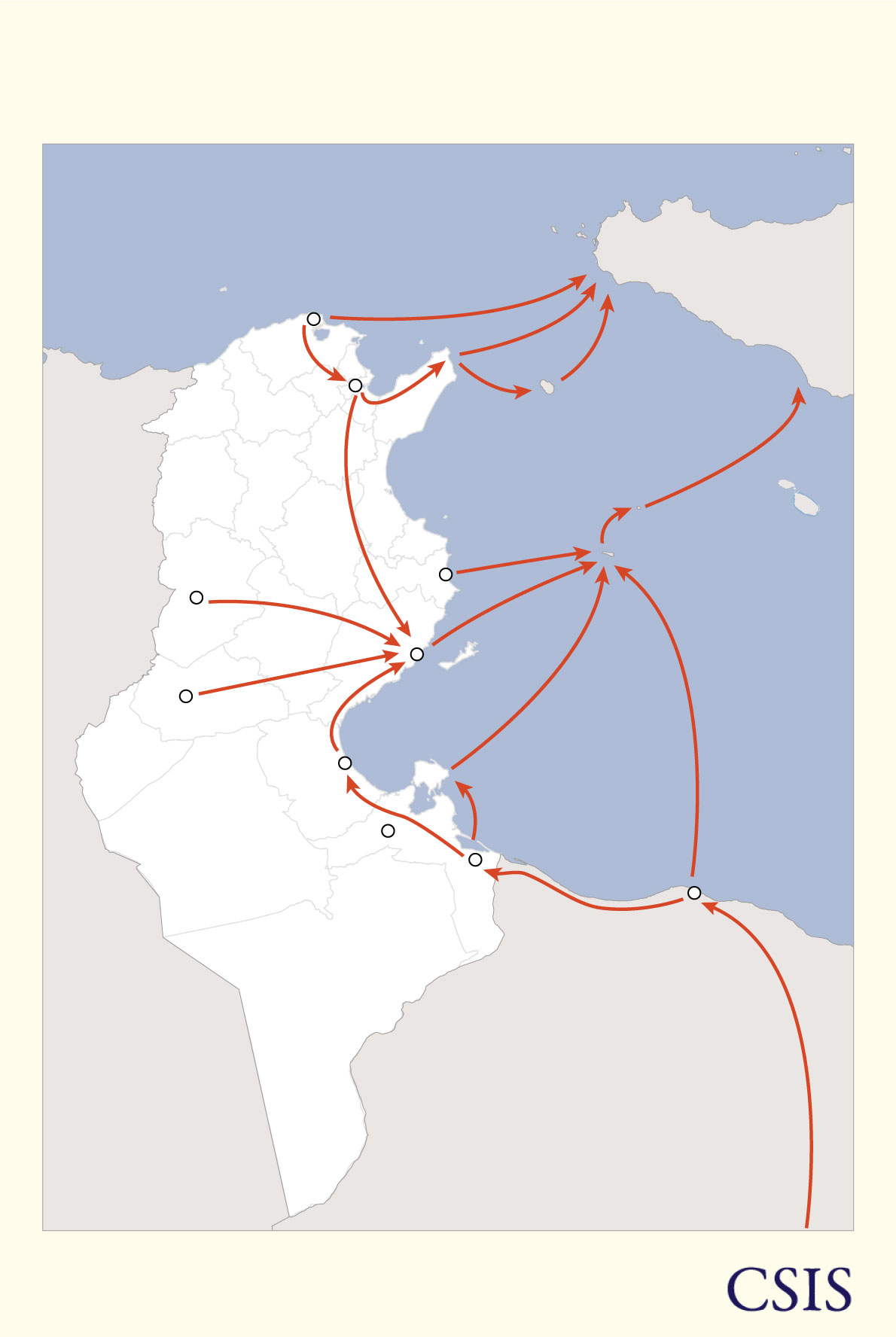

Djerba is close to the Tunisia-Libya border, along a common migration route through the central Mediterranean. The route typically includes migrants from Algeria, Libya, Tunisia and Egypt traveling to Italy, mainly Sicily, Lampedusa, and Malta. This route is considered to be the deadliest migration route in the world.

Every migration route has its chokepoints, but the routes that cross the Mediterranean have the most. Chokepoints are a congested part of migration routes that previously allowed large numbers of people to cross into Europe, where governments have now enforced new policies that make those journeys much harder than they were.

Will Todman, deputy director and senior fellow in the Middle East Program at CSIS, provided an example. “Some people who thought that Egypt might be a promising way to travel to Italy may now be stuck in Libya because of the externalization policies that the EU and European states have embarked upon.”

Externalization Policies

Destination states make externalization policies, a kind of migration management strategy, to push their borders outward and stop prospective migrants from reaching their territory without prior authorization or vetting.

As a consequence, chokepoints are created at the departure countries. Not every place where there are many migrants, asylum seekers, or refugees gathered is necessarily a chokepoint. Some refugees just try to stay as close to their homelands as possible and aren’t necessarily trying to get to Europe.

Gatekeepers and

Departure Points

Ever since Morocco became the European Union’s migration gatekeeper in North Africa, Libya, and Tunisia have emerged as key departure points for sub-Saharan migrants, especially those heading towards the Italian island of Lampedusa. However, these two countries have also been approached by the European Union in the name of externalizing migration control.

For years, the European Union has outsourced its border control to North African nations like Tunisia, transferring the responsibilities of irregular migration to them. This strategy is focused on enhancing the capacity of these countries to monitor and manage their borders; Tunisia‘s transformation into a migration hub has placed it at the center of European efforts to limit migration flows.

This approach often involves substantial financial aid, such as the controversial 150 million euro deal between the European Union and Tunisia in 2023. While intended to bolster security and reduce crossings, this funding frequently prioritizes militarization over addressing the underlying causes of migration.

For example, Italy helped train and equip Libya’s Coast Guard in 2017, which functions like the European Union’s proxy force. Despite numerous reports of migrant abuse, Italy and Libya’s bilateral pact was renewed in 2023. Poor conditions in Libya have pushed migrants to find alternative routes on their way to Europe, like Tunisia.

Migration Flows Through the Tunisian Coast

Mediterranean Sea

ITALY

Bizerte

Tunis

Pantelleria

(ITALY)

Lampedusa (ITALY)

Chebba

Kasserine

Sfax

Gafsa

Gabes

TUNISIA

Madenine

Tripoli

Ben Guerdan

ALGERIA

LYBIA

Tunisia and the European Union

In 2023, Tunisia became the primary country of embarkation for migrants seeking to reach Europe, eclipsing Libya, which had been the main North African departure point for years. At least 97,306 migrants arrived in Italy from Tunisia in 2023, three times as many as in 2022.

In July 2023, the EU-Tunisia migration deal saved Tunisian President Kais Saied’s country from bankruptcy, but in return, Tunisia had to commit to curbing migration to Europe. Since then, his country has become a key partner of the European Union in the fight against migration on the Central Mediterranean route.

Kais Saied is a challenging partner of the European Union in migration management and border externalization. He has taken Tunisia along an increasingly authoritarian path in recent years, but he argues he can provide political stability and curtail the flow of migrants to Europe.

Border externalization, combined with policies that worsen conditions for migrants in transit countries, are among the primary factors responsible for chokepoints, especially across the Middle East and North Africa region.

Impacts on Migrants

Taking into consideration that the Central Mediterranean route is the most dangerous route in the world, it’s expected that the people crossing it face many difficulties along the way. However, people are willing to face these challenges for several reasons, such as their need to escape the extreme violence and insecurity they face back in their homeland, or their need to protect their own and their families’ rights and freedoms, which are constantly violated.

High Risk and Dangerous Journeys

Choosing the Central Mediterranean route for the journey that may or may not provide them with a better life is not the first choice for people fleeing an already unsafe situation, according to the Norwegian Refugee Council. The fact that people risk crossing this geographical area is a testament to their desperation and need to escape the conditions that torment them back home. Todman explained, “A lot of migrants have harrowing stories of torture, of being detained, of sexual violence as well . . . They can languish in these conditions for years.”

Apart from that, smuggling networks are one of the most frequent obstacles people encounter on their way. Migrants are often in need of smugglers who promise to transport them from the Tunisian ports to Lampedusa and from there to the Italian mainland in exchange for exorbitant amounts of money. The smuggling industry in the Central Mediterranean was estimated to be valued at as much as $370 million in 2023.

But many get trapped in a never-ending cycle between the coasts. After the new EU deals with Tunisia and the crackdown on smuggling, Todman explained that “more migrants are actually choosing to attempt the crossing on their own, without the support of these smugglers. That means they are often embarking on vessels that are even less safe, even more overcrowded.”

That’s how the high rates of shipwrecks on the Central Mediterranean route arose, which have caused thousands of deaths and missing persons. But even if their vessel manages to stay afloat, they will likely be pushed back, putting them at risk of being detained or being forced to return to their conflict or crisis-affected country, which is illegal according to the Refugee Convention.

A Human Rights Watch investigation cited African asylum seekers saying that when the Tunisian Coast Guard intercepted them after their boat left the coast near Sfax, heading toward Italy, they deliberately tried to create waves just to push them back to shore in Sfax. Security forces then beat them using truncheons. A Guinean boy said that one officer had threatened them, saying, “If you return again [to Tunisia], we will kill you.”

Trapped on this dangerous route, they don’t even have the option to continue their journey to their final destination or a safer country. The policies applied regarding migration, hinder the journeys of migrants, with the result of trapping them in a back-and-forth route between Tunisia and Italy, thus in a hazardous condition.

Human Rights Deprivation

The number one thing people fleeing sub-Saharan and North African countries need is safety and stability, or, in legal terms, asylum. Although seeking asylum is a human right, it is often difficult for migrants to gain this legal status. The closest destination when leaving Tunisia is Italy, but the Italian government offers no clear path for asylum seekers from these countries of origin.

This obstacle often leads asylum seekers to cross the borders illegally. Nonetheless, the Refugee Convention explicitly recognizes that “refugees may be compelled to enter a country of asylum irregularly to seek protection.” UN High Commissioner for Refugees has declared that “refugees should receive at least the same rights and basic help as any other foreigner who is a legal resident, including freedom of thought, of movement, and freedom from torture and degrading treatment.”

Sub-Saharan and North African migrants trying to reach Europe through the Central Mediterranean route struggle with a lack of legal assistance as well as access to healthcare, employment, and education.

Inadequate Living Conditions

The people stuck in Tunisia, unable to cross the sea to Europe live under dire conditions. That comes from the fact that asylum seekers are not being granted access to refugee camps as well as food, clean water, and safety. As the UN Refugee Agency states, an asylum seeker is a person who has left their home country under dangerous conditions, such as a war, and therefore is seeking asylum as a refugee in another country.

Even though refugee camps are not always considered safe, they often provide refugees with access to basic services. People stuck in limbo in Tunisia don’t even have the right to reach such a place. That’s why, Todman explained, “We see migrants living in really squalid conditions in Tunisia for longer periods of time. Many of these people have been forced to live in olive groves or sleep on the side of the street, for years on end.”

Mental Health Impacts

Trapped in a vicious cycle between Tunisia and Lampedusa, with no safe alternative on the horizon, many migrants and refugees have become further traumatized.

A 2019 psychological study about migration and refugees’ mental health in Tunisia reports that “while migration does not automatically imply resulting trauma, migration is a profound life transition that necessitates considerable adaptation on the part of the migrant. The way in which the life of a migrant influences their mental health evolves over time, as migration is characterized by periods of relative equilibrium and others of stress.”

At the same time, people migrating are victims of racism and discrimination, even by Tunisia’s authoritarian president himself.

Produced by Liliane De Brauwer and Eleni Kountoumadi | Background Music via Chromatic by Tom Fox

Featuring: Dr. Rochelle Davis, Associate Professor and Sultanate of Oman Chair at Georgetown University

Will Todman, Deputy Director and Senior Fellow in the Middle East Program at CSIS

Dr. Kelsey Norman, Fellow for the Middle East and Director, Women’s Rights, Human Rights, and Refugees Program at Rice University

Rethinking

Migration Policy

The Central Mediterranean has become a critical intersection of security, aid, and migration policy dynamics.

Although discussions often focus on statistics and tragedies, regional actors can shape more effective policies by better integrating these tools.

Externalizing Migration Control

In response to the influx of migration between Tunisia and Italy, the European Union has intensified border surveillance with the cooperation of Tunisia. Critics argue that these agreements shift the problem rather than solve it, leading to further consequences.

Kelsey Norman, fellow for the Middle East at Rice University’s Baker Institute, noted that “before signing a major deal with Tunisia . . . there was no human rights assessment conducted to understand what the consequences of their support would be.” The European Union frames its approach as a strategy to reduce migrant arrivals, a metric that policymakers view as successful. Instead, Tunisian authorities forced people toward the Libyan border. There, those migrating voiced their urgent need for humanitarian aid. In other words, securitization amplifies human suffering rather than addressing it.

The European Union’s heavy-handed focus on border security raises serious questions about its commitment to human rights; policies towards Tunisia essentially foster authoritarian practices, questioning the European Union’s credibility as a human rights champion.

North Africa’s Balancing Role

North African countries have acquired a dual role in the Mediterranean migration ecosystem as both transit hubs and gatekeepers. Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s engagement with the Tunisian president solidifies how the 2023 agreement between Tunisia and Italy has created a shift in migration flows, making Tunisia a key launch point for sub-Saharan migrants.

Despite their importance, North African states often lack the resources to manage migration effectively. However, as Todman observed, such assistance creates a dangerous dependency. “North African countries have an incentive to allow some migrants to keep taking this journey so that they continue to receive this kind of international support from the [European Union] and from European countries,” he explained.

The Role of NGOs: Advocacy, Monitoring, and Humanitarian Aid

With state support often lacking, nongovernmental actors have become lifelines for migrants. They offer vital humanitarian aid, advocate for more humane migration policies, and document human rights violations at borders. However, their ability to operate often depends on the approval of government authorities. As Kelsey Norman explains, “International NGOs, and often domestic NGOs, too, have to get the permission of whether it’s the Ministry of the Interior or some other ministry in order to operate.”

With the current restrictions and crackdowns, this dependency has created a restrictive environment for aid workers, particularly in Tunisia. According to Todman, “members of some of these NGOs that were providing services . . . were so scared that they refused to talk to me . . . Some said they would only talk to me if we did it in private.” As a result, much of the support available to migrants now comes from informal networks within migrant communities themselves—a fragile system with critical gaps left by government inaction and NGO suppression.

Towards a Comprehensive

Strategy

The central Mediterranean route, especially the channel between Tunisia and Italy, has become a turning point in Europe’s migration crisis and, most importantly, a complex and deeply human issue. European actors have increasingly portrayed Tunisia as a weak link in migration management, a narrative that justifies stricter policies.

But these measures come at a high cost: people find themselves trapped in squalid conditions. This strategy, Todman argued, is deliberate. “Almost everyone involved has an interest in making life as hard as possible for migrants in Tunisia so that they don’t even get as far as Tunisia,” Todman said. Migration management policies have not only failed to stem the flow of migrants to Europe but have also empowered antidemocratic actors. The entrenchment of these actors and their failure to meet the needs of their people has become an additional driver of displacement. Ultimately, the conversation returns to a fundamental question about whose responsibility migrants are.

A more sustainable approach requires different governments to open legal migration pathways. Safer alternatives would ease the pressure on transit countries and meet Europe’s labor demands. With an aging population and a growing need for workers in Europe, integrating migrants into the workforce through legal channels could provide a practical solution, benefiting both sides. Yet, the European Union continues to prioritize border enforcement, prolonging a system where migrants are forced into irregular routes, enriching smugglers, and deepening the crisis in North Africa. The intensified externalization policies and the established agreements with North African countries are set to manage migration flows and prevent departures toward Europe. A recent EU approach considering the establishment of deportation camps outside its borders to push back asylum seekers is raising questions on whether this is a realistic response to migration pressures.

Migration has always been part of human history and will continue to be. It is not an anomaly to be eradicated but a reality to be managed. Without a shift in strategy, the Mediterranean will remain a graveyard for those seeking a better future, and the policies intended to control borders will only deepen its challenges.

Authors

Photo Credits

Hover to see image locations and credit information.

Tunisian National Guard operation against African irregular migrants who try to reach Europe via the Mediterranean Sea, Sfax, Tunisia. | Yassine Gaidi / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Tunisian National Guard operation against African irregular migrants who try to reach Europe via the Mediterranean Sea, Sfax, Tunisia. | Yassine Gaidi / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Tunisian National Guard operation to prevent African irregular migrants from reaching Europe via the Mediterranean Sea, Sfax, Tunisia. | Yassine Gaidi / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Tunisian National Guard operation to prevent African irregular migrants from reaching Europe via the Mediterranean Sea, Sfax, Tunisia. | Yassine Gaidi / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Migrants before being transferred from Lampedusa Island to the Italian mainland. | Valeria Ferraro / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Migrants before being transferred from Lampedusa Island to the Italian mainland. | Valeria Ferraro / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, announcing at a press conference the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding between Tunisia and the European Union at the Presidential Palace in Tunis, Tunisia, on July 16, 2023. | Photo by Tunisian Presidency / Handout / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, announcing at a press conference the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding between Tunisia and the European Union at the Presidential Palace in Tunis, Tunisia, on July 16, 2023. | Photo by Tunisian Presidency / Handout / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

A boy in a bus as the massive transfer of migrants is taking place from the Sicilian island of Lampedusa to the Italian mainland to alleviate the migration flow to Italy in 2023. | Valeria Ferraro/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

A boy in a bus as the massive transfer of migrants is taking place from the Sicilian island of Lampedusa to the Italian mainland to alleviate the migration flow to Italy in 2023. | Valeria Ferraro/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

A view of a street in which African migrants live in tents in Tunis, 200 meters from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) building in Tunis in 2024. | Hasan Mrad/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

A view of a street in which African migrants live in tents in Tunis, 200 meters from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) building in Tunis in 2024. | Hasan Mrad/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Migrants wait for the transfer on Italy's Lampedusa Island, which is overwhelmed after more than 100 migrant boats arrived according to the Italian Red Cross. | Valeria Ferraro/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Migrants wait for the transfer on Italy's Lampedusa Island, which is overwhelmed after more than 100 migrant boats arrived according to the Italian Red Cross. | Valeria Ferraro/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Italian police surround the rescue ship Aita Mari to guard the landing of African migrants at the port of Cittavecchia, Italy, in 2023. | Ximena Borrazas / SOPA Images / LightRocket via Getty Images

Italian police surround the rescue ship Aita Mari to guard the landing of African migrants at the port of Cittavecchia, Italy, in 2023. | Ximena Borrazas / SOPA Images / LightRocket via Getty Images

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni (L) meets with the Tunisian President Kais Saied (R) during her visit in Tunis, Tunisia, on June 06, 2023. | Photo by Tunisian Presidency / Handout / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni (L) meets with the Tunisian President Kais Saied (R) during her visit in Tunis, Tunisia, on June 06, 2023. | Photo by Tunisian Presidency / Handout / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Migrants wait in the queue outside the hotspot in Lampedusa, Italy, on September 14, 2023. | Photo by Valeria Ferraro / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Migrants wait in the queue outside the hotspot in Lampedusa, Italy, on September 14, 2023. | Photo by Valeria Ferraro / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

A wooden boat with approximately 100 people of different nationalities on its journey through the Mediterranean to Lampedusa on March 29, 2021. | Photo by Carlos Gil via Getty Images

A wooden boat with approximately 100 people of different nationalities on its journey through the Mediterranean to Lampedusa on March 29, 2021. | Photo by Carlos Gil via Getty Images

Special Thanks:

Story: Marla Hiller

Video: Michael Kohler

Audio: Gina Kim

Data: Fabio Murgia

Editorial: Mark Donaldson & Sarah B. Grace