TRACKING

TRANSATLANTIC

DRUG FLOWS

Cocaine's Path from South America

across the Caribbean to Europe

The global cocaine trade has seen seismic shifts in the last decade as drug traffickers looked beyond the United States to set their sights on more lucrative markets in Europe.

Cocaine consumption in Europe has increased significantly over the last decade. The rise of cocaine has caused an unprecedented wave of drug-related violence across Europe, especially in port cities like Rotterdam. As drug use has increased, so have drug-overdose deaths.

Governments have struggled to respond to this rising threat to public health and security.

Understanding how cocaine makes its way from South America through the Caribbean to Europe, as well as the geographic and political nature of the trafficking routes that connect them, will be critical for crafting effective solutions to this crisis.

Europe's Cocaine

Problem

In 2020, Western and Central Europe comprised 21 percent of the global demand of cocaine. The drug is now the second most consumed illicit drug on the entire continent behind cannabis.

Europe has become an attractive destination for drug traffickers seeking higher profits and lower risks. This is due to higher market prices and lesser legal penalties for possession and consumption than in the United States.

While a kilogram of cocaine is priced at around $28,000 in the United States, the same kilogram is priced at around $40,000 in places like France and Spain—and a staggering $219,454 in Estonia.

Furthermore, European interdiction efforts in Europe and the Caribbean territories do not match U.S. disruption efforts in the Western Hemisphere. Available data suggests the European Union spends only $3-4 billion on supply-side reduction in comparison to $17.4 billion for the United States. According to European officials, this allows border security forces to interdict only around 10–12 percent of the total flow of cocaine into the continent.

Without a multipronged approach to curb Europe’s cocaine demand through higher legal penalities and transatlantic interdiction efforts, the cocaine market there will continue to boom—and with it, drug violence and health threats.

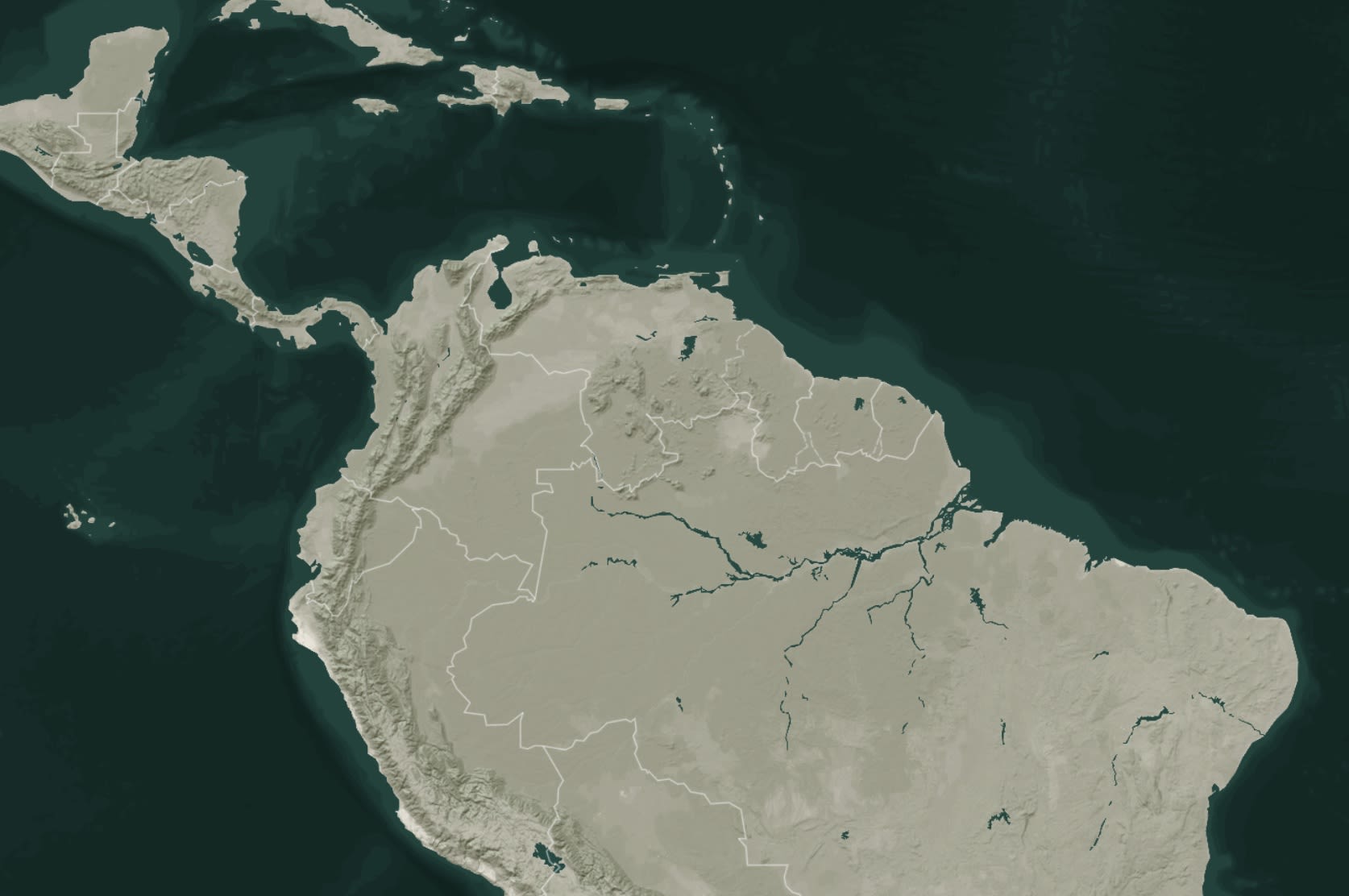

The problem begins at the source of production: South America.

Stage 1

South America:

Cultivation & Crossing Points

Cocaine is produced from the coca plant, which is grown throughout South America. The majority of coca harvesting takes place in three countries, Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru, which also serve as the starting point of the drug trade to Europe.

In 2020, these three countries alone grew an estimated 99.5 percent of the global coca cultivation.

Peru, located on the Pacific coast, is able to reach both the United States and Europe by transporting drugs through countries with high levels of trade with the European Union like Ecuador and Brazil.

Colombia’s dominance of the cocaine market, as well as its proximity to Mexico and the Caribbean, makes it the de facto supplier of the United States. In 2021, 98 percent of the forensic analyses conducted on cocaine seized in the United States traced its origin to Colombia.

However, cocaine seized in Europe had a more complex breakdown, with 67 percent originating in Colombia, 27 percent in Peru, and 5 percent in Bolivia.

Although the refined cocaine is occasionally transported directly to Europe from South America, increased patrolling in areas like Colombia’s coastline has pushed drug traffickers to diversify their routes, including through the Caribbean.

To get to the Caribbean, drug traffickers favor transiting from Colombia through Venezuela.

The Colombia–Venezuela border in particular has lax controls on the Venezuelan side, and some members of the Venezuelan military are involved or support the trafficking of drugs.

A worker in Colombia sprinkles lime over crushed coca leaves as they are processed into coca paste.

A worker in Colombia sprinkles lime over crushed coca leaves as they are processed into coca paste.

These factors allow for the flow of cocaine between the two countries, mainly through the crossing points in Catatumbo, Vichada, and Guanina.

Once cocaine has arrived in Venezuela, it is then transported to the Caribbean through the Guajira and Paraguaná Peninsulas.

Stage 2

The Caribbean:

A Transshipment Paradise

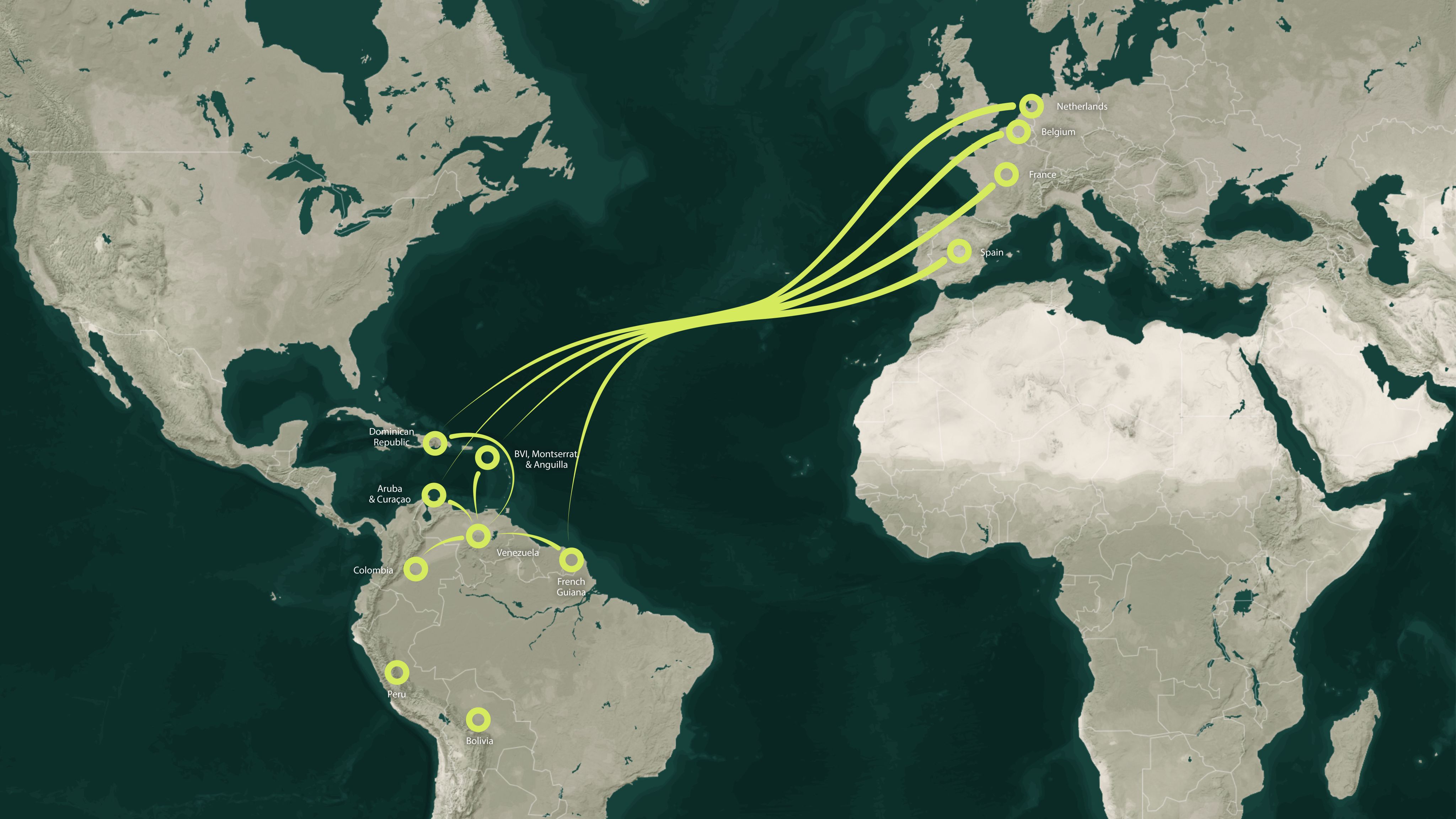

The Caribbean’s low interdiction capacity and proximity to South America makes it an attractive route for drug traffickers looking for ways to transport large amounts of cocaine from South America to Europe.

Criminal groups thrive in an atmosphere of corruption and impunity. When cocaine goes through ports and airports, drug traffickers often rely on bribes or compromised authorities to ensure their illicit cargo passes swiftly and without detection.

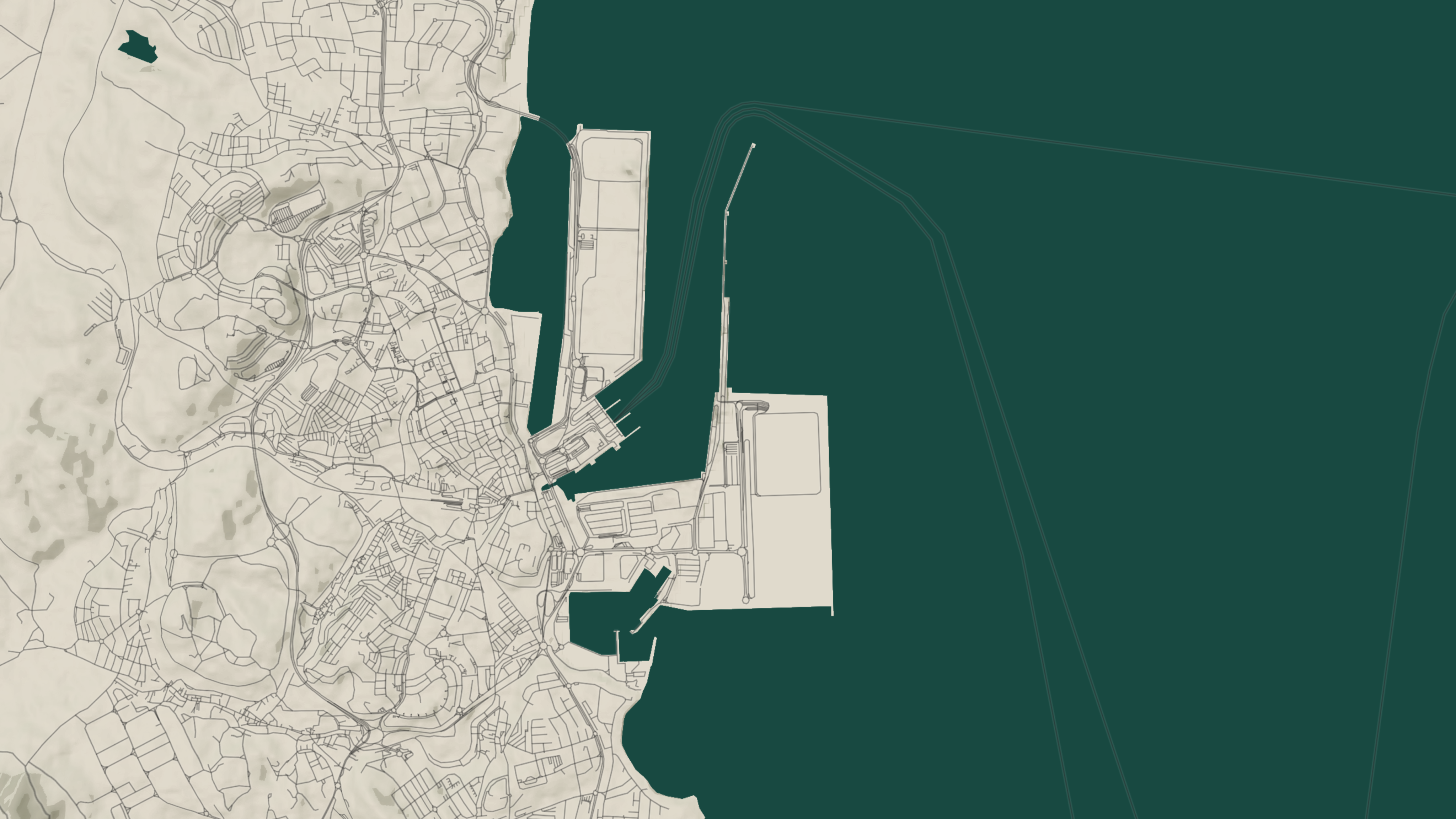

This intersection of corruption and impunity is best seen in commercial ports. It has been extensively reported that criminal groups have infiltrated the commercial operations of ports that enables them to introduce cocaine into shipping containers destined to Europe.

Cargo vessels offer one of the most advantageous methods of transporting cocaine because of the large volume of trade between the Caribbean and Europe.

Interact with the 3D visualization below to learn some of the ways traffickers use shipping containers to conceal cocaine.

While shipping containers represent the most lucrative method of transporting cocaine via sea, traffickers are also known to use mules to transport cocaine via air. Other methods of transportation across the Caribbean include go-fast boats, small, privately owned aircraft, and narcosubs.

There are a multitude of paths drug traffickers may take through the Caribbean into Europe, including island hopping and moving through European overseas territories.

Route 1:

Island Hopping

“Island hopping” involves moving large amounts of cocaine from island to island, typically in go-fast boats. The ultimate goal is reaching a large port or airport, such as the port of Caucedo in the Dominican Republic.

By moving cocaine from island to island in small go-fast boats, traffickers reduce the chance of being detected by maritime patrol. Drug traffickers typically transport the cocaine during nighttime and leave it on deserted beaches for the next transportista to move it up the supply chain until it reaches a major port.

A sample route may begin with cocaine leaving the small Venezuelan port town of Guiria toward Trinidad and Tobago. Trinidad and Tobago is only seven miles away from the Venezuelan coast, typically a 12-minute boat ride.

From there, traffickers can make multiple stops along the Lesser Antilles all the way to Hispaniola, either to the Dominican Republic or to the Haitian side of the island.

The Dominican Republic’s six container ports and bustling airports present multiple opportunities for moving people, goods, and drugs.

The Dominican Republic reported an annual seizure of 27.7 tonnes (30.5 tons or 61,000 pounds) of cocaine in 2022, which is triple the amount seized in 2020. Cocaine leaving the Dominican Republic is typically destined for Spain, mainly due to the shared language, though recent reports claim Dutch and Dominican criminal groups are building stronger ties.

Weak governance and limited economic opportunities in the Caribbean are two of the main vulnerabilities that drug traffickers exploit. Stronger institutions and stronger local economies therefore have the potential to reduce the likelihood of local officials and dock workers participating in part of the drug trade supply chain.

Route 2:

Europe in the Caribbean

European overseas territories offer distinct advantages to drug smugglers over other parts of the Caribbean. They include self-governing territories in the case of the Kingdom of the Netherlands or the United Kingdom, or in the case of France, are an integral part of the country. They usually include a common language, business connections, and family ties, in addition to direct transportation links to Europe by air or maritime routes. In the case of French Guiana, it also shares a common currency, the euro.

The French Territories

French Guiana, Guadeloupe, and Martinique are integral parts of France, each one being one of the country’s 101 departments. These territories are also part of the European Union. European passport holders can travel to these territories and back to Europe visa-free.

This route starts with cocaine leaving Colombia and Venezuela in small planes transiting through Guyana or the porous border with Suriname.

In Suriname, drug traffickers cross the Maroni River, a natural border between Suriname and French Guiana. Once in French Guiana, the cocaine departs in cargo vessels or by mules that take commercial flights to France.

In a report presented to the French Senate in September of 2020, it was estimated that between 15 and 20 percent of the cocaine reaching France comes from French Guiana.

The Dutch Territories

The islands of Bonaire, Saint Eustatius, and Saba are special municipalities within the Netherlands and are jointly referred to as the Caribbean Netherlands. Aruba, Curaçao, and St. Maarten are independent countries that, along with the Netherlands, are part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Royal Netherlands Navy plays a part in defense and security, including from bases in Curaçao and Aruba. In 2022, it intercepted over 35 tonnes (38 tons) of cocaine in the waters of its territories in the Caribbean.

Cocaine shipments from Venezuela enter the European Dutch territories via go-fast boats. The distance between Aruba and Venezuela is only 14.3 miles.

From Aruba and Curaçao, cocaine is shipped directly to the Netherlands via sea or air, or it continues its transshipment route to the eastern Caribbean.

The route may include another transshipment point in Haiti due to its lack of port controls, and the cocaine is sometimes later transported by land to the Dominican Republic before it departs for Europe.

The British Territories

The British Overseas Territories also play a role as transshipment points for cocaine.

In November 2020, the British Virgin Islands (BVI) police seized a record 2,353 kilograms of cocaine from the residence of a BVI police officer. This was worth 75 percent of the islands’ entire national budget and was “one of the largest seizures in the history of any British Overseas Territory of the UK.”

Less than two years later, in April 2022, BVI premier Andrew Fahie was arrested along with the territory’s ports authority managing director and her son for allegedly smuggling cocaine into the United States.

The drug trade has significantly decreased the region’s stability.

The increased traffic of cocaine in the Caribbean has brought a significant increase in violence and has exacerbated existing corruption in the region.

This corruption and violence have compounded existing gender-based violence, gang activity, and high firearms availability.

Curbing this trade is critical for restoring security across the region.

Stage 3

Europe: The Final Destination

When shipments of cocaine finally reach Europe, there are three primary points of entry. Over 70 percent of the cocaine entering Europe goes through Belgium, the Netherlands, or Spain.

The main methods of transportation are via cargo, sailing, and fishing vessels. Some drugs are trafficked through air transportation, but this is less profitable as the volumes drug traffickers can transport are smaller compared to the amount they can send via maritime routes in shipping containers.

Once the cocaine has reached its destination in Europe, the drugs are collected by drug extractors. In the Netherlands, drug extractors are typically young men often recruited from underprivileged areas and paid around €2,000 per kilogram of cocaine collected. Unless they are actually caught with drugs, they only pay a fine of €100 for trespassing into the port.

Port workers or company employees share container reference codes with these extractors to allow them pick up the drugs from the specific shipping containers.

Containers transporting perishable goods are regularly abused for this purpose, due to their expedited customs timeframe.

Challenges for

European Ports

Port and airport security officials attempting to stem the flow of cocaine into Europe must reckon with the continent’s vast number of ports and airports, any of which can be an entry point.

According to a Europol report, European ports handle over 90 million containers each year. However, only 2 to 10 percent can be physically inspected, making the widespread detection of drugs nearly impossible.

Four major ports in particular have seen a dramatic increase in the amount of cocaine being trafficked

Port 3

Valencia

The port of Valencia in Spain is the fourth-largest port in Europe. Before the emergence of the ports of Antwerp and Rotterdam, Spain had been the main entry point of cocaine arriving from the Andean countries. The port seized 2.59 tonnes (2.85 tons) of cocaine in 2019 and 11.5 tonnes (12.6 tons) in 2022, a 344 percent increase.

Port 4

Algeciras

The Spanish port of Algeciras is the sixth largest in Europe. 8.7 tonnes (9.5 tons) of cocaine were seized in 2018, but seizures dropped off in subsequent years until rebounding in 2022 when 8.84 tonnes (9.74 tons) were seized. On August 25, 2023, 9.4 tonnes (10.3 tons) of cocaine were seized hidden in a single container loaded with bananas from Ecuador.

Port 5

Le Havre

An emerging port of concern to law-enforcement officials is Le Havre in France. In 2021, nearly 45 percent of the cocaine entering France transited through that port.

France has also recorded a 554 percent increase in cocaine seizures from 2010 to 2022. This trend is expected to continue as customs and port security tighten in Belgium and the Netherlands, driving traffickers to France.

For drug traffickers, these ports across Europe present a unique opportunity to increase their monetary gains, extend their influence, and lower operational risk.

Recommendations

Cocaine’s path from South America through the Caribbean to Europe sows destruction and instability at every stage of the journey.

International cooperation is imperative for creating solutions that are both comprehensive and sustainable for all countries involved.

European stakeholders and Caribbean states must create a cohesive counternarcotics strategy.

This should combine Caribbean nations’ understanding of their region with future improvements to interdiction capabilities in Europe.

A Caribbean-European joint strategy should also prioritize strengthening the interdiction capacity of regional organizations like the Caribbean Community Implementation Agency for Crime and Security (CARICOM IMPACS). Additionally, increased cooperation with European overseas territories that serve as a gateway to the continent will be vital.

Finally, public-private sector cooperation among shipping container companies and the governments affected by the drug trade is of utmost importance. Shipping companies should prioritize rigorous employee vetting and regular screening of all port and shipping containers.

Conclusion

The Caribbean’s strategic geography, location, and historical ties make it the perfect link between South America and Europe. However, criminal groups take advantage of these ties to smuggle enormous amounts of cocaine across the Atlantic.

Multiparty cooperation among criminal groups at the local, regional, and international levels has enabled the transatlantic drug trade to flourish. Only equivalent cooperation among European and Caribbean governments and the private sector can begin to effectively counter the flow of cocaine.

Made possible by the generous support of the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement at the U.S. Department of State.

Authors

Christopher Hernandez-Roy, Deputy Director and Senior Fellow, Americas Program

Rubi Bledsoe, Program Coordinator, Americas Program

Andrea Michelle Cerén, Intern, Americas Program

iDeas Lab Story Production

Editorial & production by: Sarah B. Grace & Claire Smrt

Editorial assistance & research by: Marla Hiller

Design by: Sarah B. Grace

Maps by: Michael Kohler

3D Animation by: Fabio Murgia

Data visualizations by: Michael Kohler & Sarah B. Grace

Satellite Imagery Analysis by: Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. & Jennifer Jun

Copyediting support by: Katherine Stark & Jeeah Jehanne Lee

Photo Credits

□ Coca farm: Edinson Arroyo/AFP via Getty Images.

□ CARICOM flags: Trinidad Express Newspaper/AFP via Getty Images.

□ Bananas: adobestock3d via Adobestock.

□ Air conditioning unit: Jack via Adobestock.

□ Cardboard boxes on wood pallet: Perig via Adobestock.

□ Shipping container: Game Ready via Adobestock.