The Price of Gold

The Impacts of Illegal Mining on Indigenous Communities in Venezuela and Brazil

Illegal mining is causing devastation to the Indigenous populations of Venezuela and Brazil.

Illegal gold mining specifically is being used to fund illegal syndicates, cartels, and even governments. It has led to deforestation and environmental contamination—and has contributed to birth defects, malnutrition, and other health issues among local communities. The Venezuelan government has encouraged the continuation of this operation, while Brazil has signaled an intention to protect its Indigenous people and lands. Although it seems impossible for illegal gold mining to be stopped, there are critical steps that can be taken to mitigate the consequences and document the crimes of illegal mining.

Illegal Mining Explained

Illegal mining can be defined as any type of mining activity that violates existing laws. This type of mining encompasses everything from individuals searching for precious metals to earn additional income to complex criminal operations.

In the case of Latin America, there are high rates of illegal mining. Illegal gold mining is especially common in the territories of Indigenous groups, such as the Yanomami tribe in Venezuela and Brazil.

There are many layers to this lucrative business that involve multiple actors, including organized crime groups and state officials.

Criminal organizations facilitate much of the illegal mining in Venezuela and Brazil.

They control the areas where extraction and transportation of the illegally extracted gold occurs, and they often receive a cut of the profits.

The organized crime groups are able to carry out these operations by utilizing their pre-existing drug-smuggling networks, connections to state officials, and by using force against anyone that opposes them.

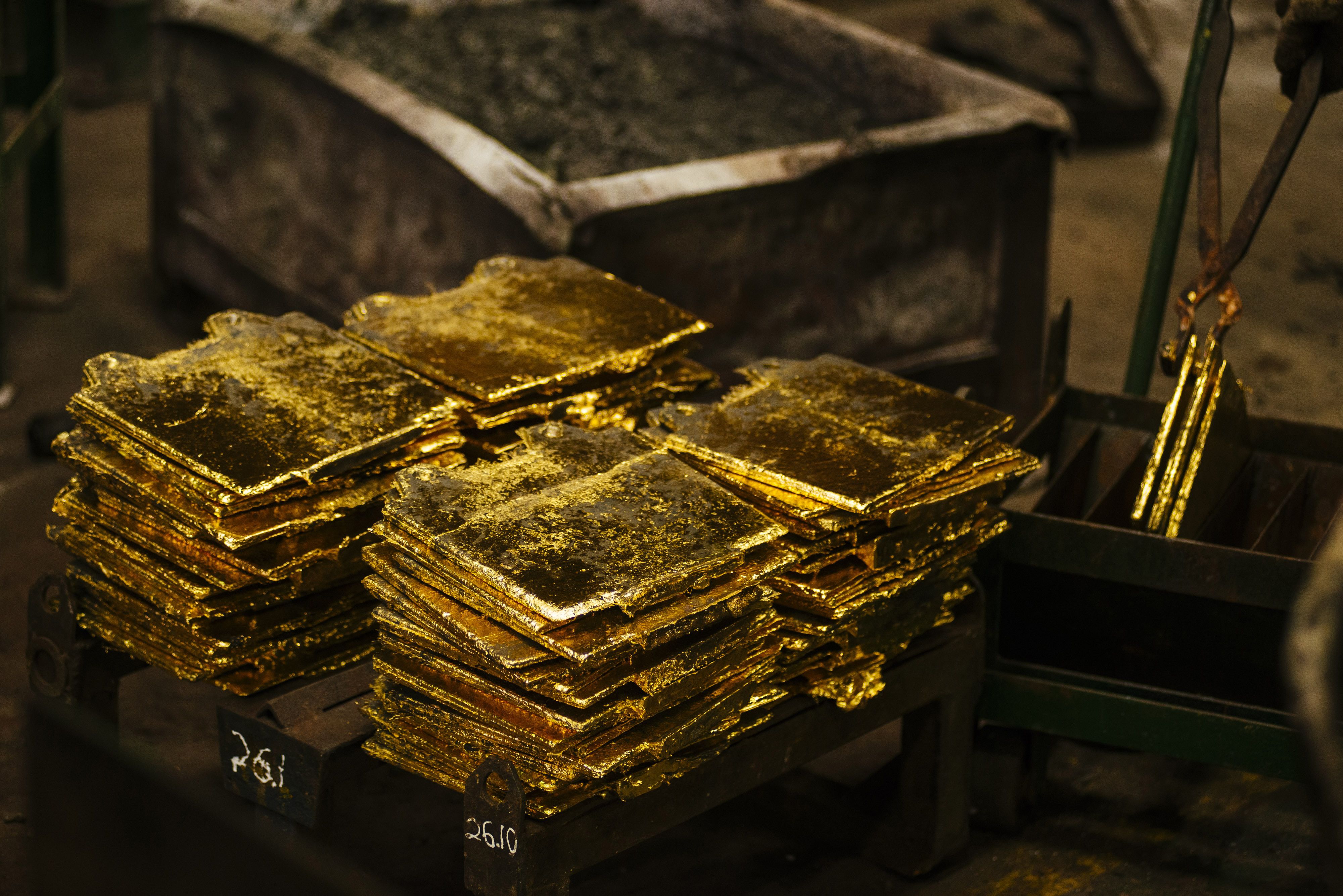

Illegal gold mining is an extremely enticing venture for these organized crime groups due to its high profits and how easy it is to launder the proceeds.

According to a 2023 report from the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, 75 tons of gold are illegally extracted in Venezuela annually, which brings in a revenue of approximately $4.8 billion.

Illegal Gold Mining Process

Exploration

A set of informal activities that identify and locate gold deposits without legal authority or supervision. By doing surface sampling, or utilizing metal detectors to find the gold-rich locations.

Establishment of Land Claims

Once a potential site is discovered, illegal miners can establish claims on the soil without legal license, and indigenous lands.

Extractions

Illicit miners collect gold from the ground with crude tools and methods. This include hand-digging, panning, and the use of heavy machinery in prohibited locations to recover gold-bearing ore that contributes to conflicts.

Processing

Ore recovered from illegal mining activities is often processed on-site using fundamental processes such as, gravity extraction, mercury combination, and or cyanide, which includes smelting and refining.

Environmental Degradation

The illicit gold mining often leads to severe environmental damage, soil erosion, water pollution, etc. The use of mercury and other harmful compounds in gold mining and processing cause water contamination and long-term environmental damage.

Gold Supply-Chains

The illegally mined gold supplies a variety of channels that include refineries, trade hubs, and jewelry manufacturers, where it can be combined with lawfully sourced gold and sold to consumer worldwide.

Transportation and Smuggling

This concept is when the illegal mined gold frequently transported by land and sold through informal channels, that operate across borders to avoid taxes, tariffs, and regulatory supervision.

Money Laundering

The profits from the gold mining activities are laundered through the regular bank system to cover up its illegal source. Which can be used as a criminal organization or fraud to earn revenue, and fund other illegal activities.

Impacts of Illegal Mining

Environmental Effects

Illegal gold mining has detrimental effects on the environment.

Indigenous groups on the Brazil and Venezuela border, such as the Yanomami, face these environmental repercussions, specifically the impacts of deforestation and mercury poisoning, which negatively impact the ecosystem in which the Yanomami people engage in agriculture and hunting.

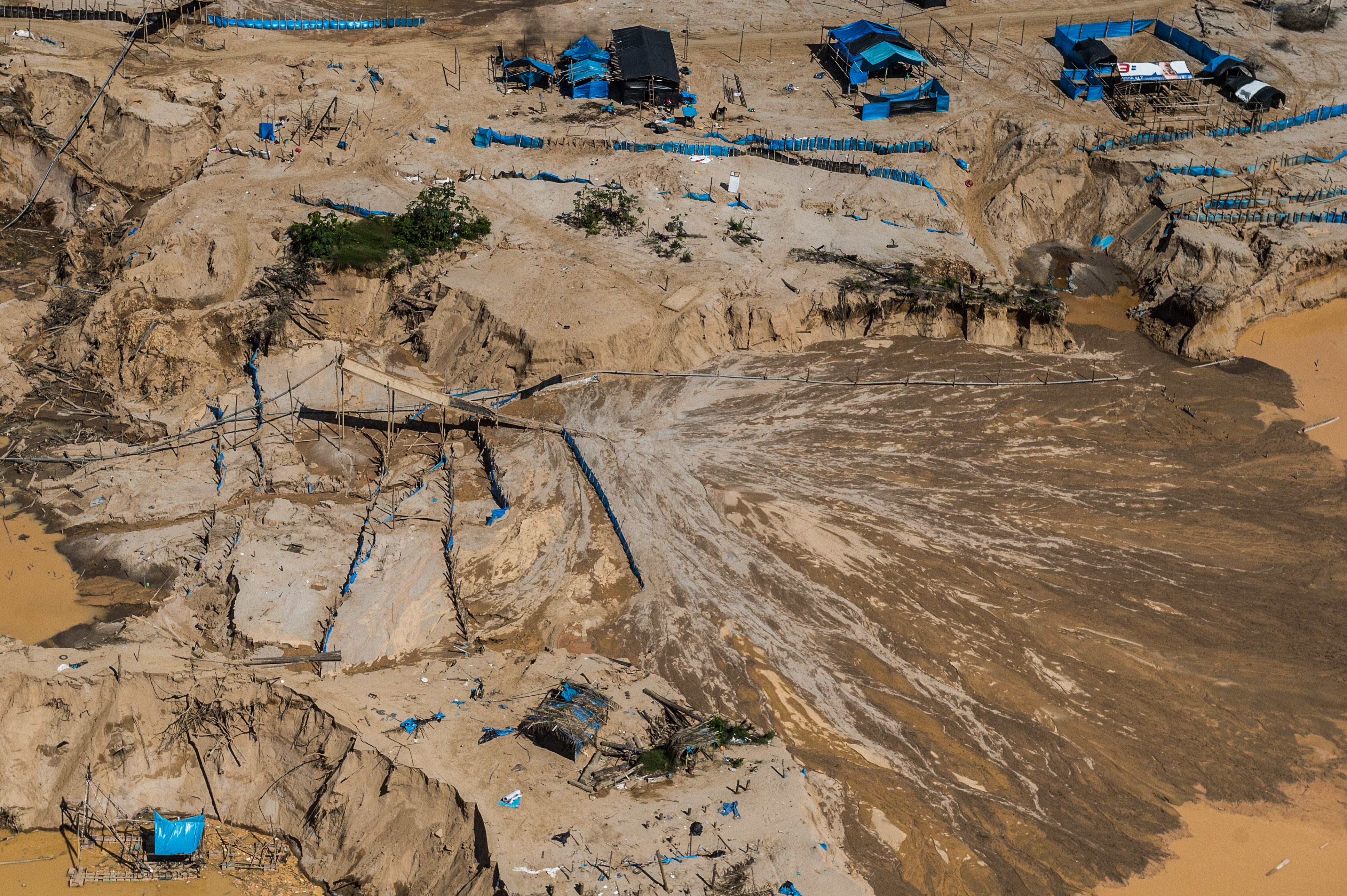

For example, the mining industry involves the deforestation of a large amount of the forest in which the Indigenous people reside. According to Insight Crime, an estimated 140,000 hectares was destroyed between 2016 and 2020 in Venezuela.

Another way mining has hurt the environment is through the mercury that is used to extract gold, which pollutes water sources and leeches into nearby land.

Crops and animals in these areas can be poisoned by mercury, which can then damage the surrounding ecosystem and food sources for local populations.

Not only do the environmental impacts of mercury poisoning and deforestation affect the home of the Yanomami, but they harm the health of the Indigenous tribes, generating interconnected environmental and health impacts.

Health Effects

Illegal mining can create areas of stagnant water where mosquitoes can spread illnesses such as malaria to the miners.

In Brazil’s Yanomami territory alone, there are about 30,000 Indigenous people and about 20,000 workers who are involved in illegal gold mining. When the workers relocate, they further spread these diseases among the Indigenous population.

In addition, the mercury can cause harm to pregnant women by damaging their kidneys and brain or by interfering with the development of their baby.

The risks of mercury poisoning include stillbirth, low birth weight, and pre-maturity. Mercury poisoning can also cause other birth defects such as harms to the cognitive, motor, and auditory functions in children. Many women might not be able to produce breast milk because of the water contamination.

In addition, it is important to note that because of the Yanomami’s location, what happens on one side of the border can affect the entire Yanomami community.

In particular, the mercury that is used in mining pollutes the water in the area at an alarming rate. Ryan C. Berg, director of the Americas Program and head of the Future of Venezuela Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), stated that there are “instances of Venezuela’s waters being polluted and those waterways actually crossing over the border into Brazil and affecting indigenous communities there downstream.”

Without government intervention to curtail illegal mining, these environmental and health impacts will continue to escalate. However, governments in the region have not consistently been able—or in some cases, even willing—to tackle the problem.

Government Responses to Illegal Mining

Due to the Yanomami’s location across Venezuela and Brazil, their case demonstrates the stark differences between the two governments’ approaches to illegal gold mining. Venezuela’s government is often complicit in illegal mining, due in part to corruption within the current government. Brazil, on the other hand, is actively working against illegal mining and cracking down on the complex and lucrative gold trade, though it has experienced hurdles trying to implement these policies.

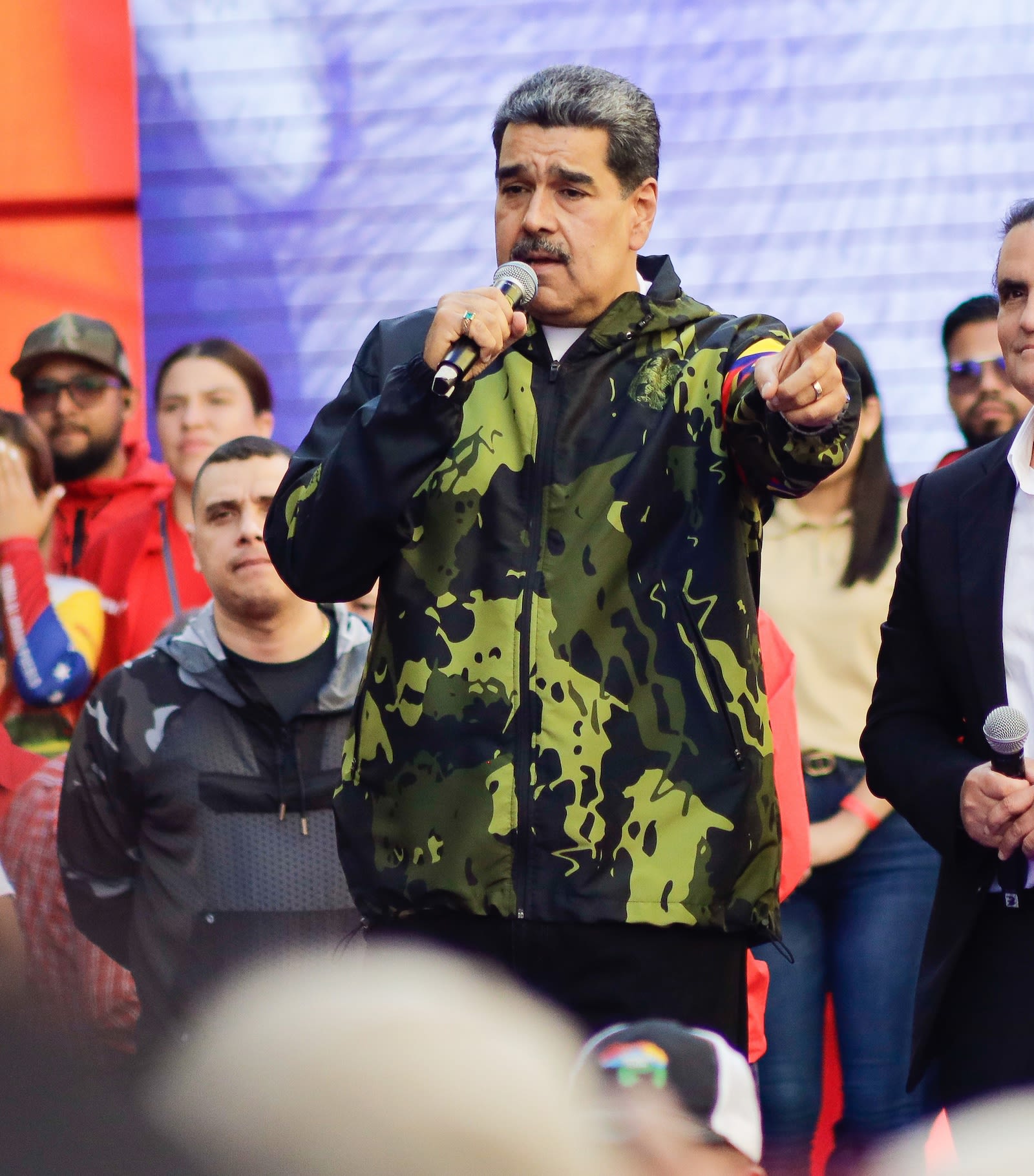

“The government of Venezuela today, the government of Nicolas Maduro, has become [...] completely corrupted [...] any senior officer in the law enforcement or military communities of Venezuela today are in some way, shape or form cooperating with and receiving some revenue from criminal organizations.”

Background Music via Storyblocks

Venezuela

Venezuela is behind Brazil in terms of the government’s protection of Indigenous people from the effects of illegal mining. Venezuela is known to have an abundance of minerals, making it a perfect place for these illegal activities to occur.

One of the primary factors in Venezuela’s inaction is government corruption, specifically under current president Nicolás Maduro. Maduro’s system of government is closely intertwined with organized crime, and he routinely uses his role in criminal consolidation to further his own interests and remain in office.

However, despite Maduro’s connection to organized crime, the Maduro administration launched a campaign in 2023 against illicit activity in prisons, drug trafficking, urban gangs, and illegal mining.

According to Insight Crime, while the government is making use of its police and military power, experts do not see these efforts as genuine attempts to put an end to criminal activity in Venezuela.

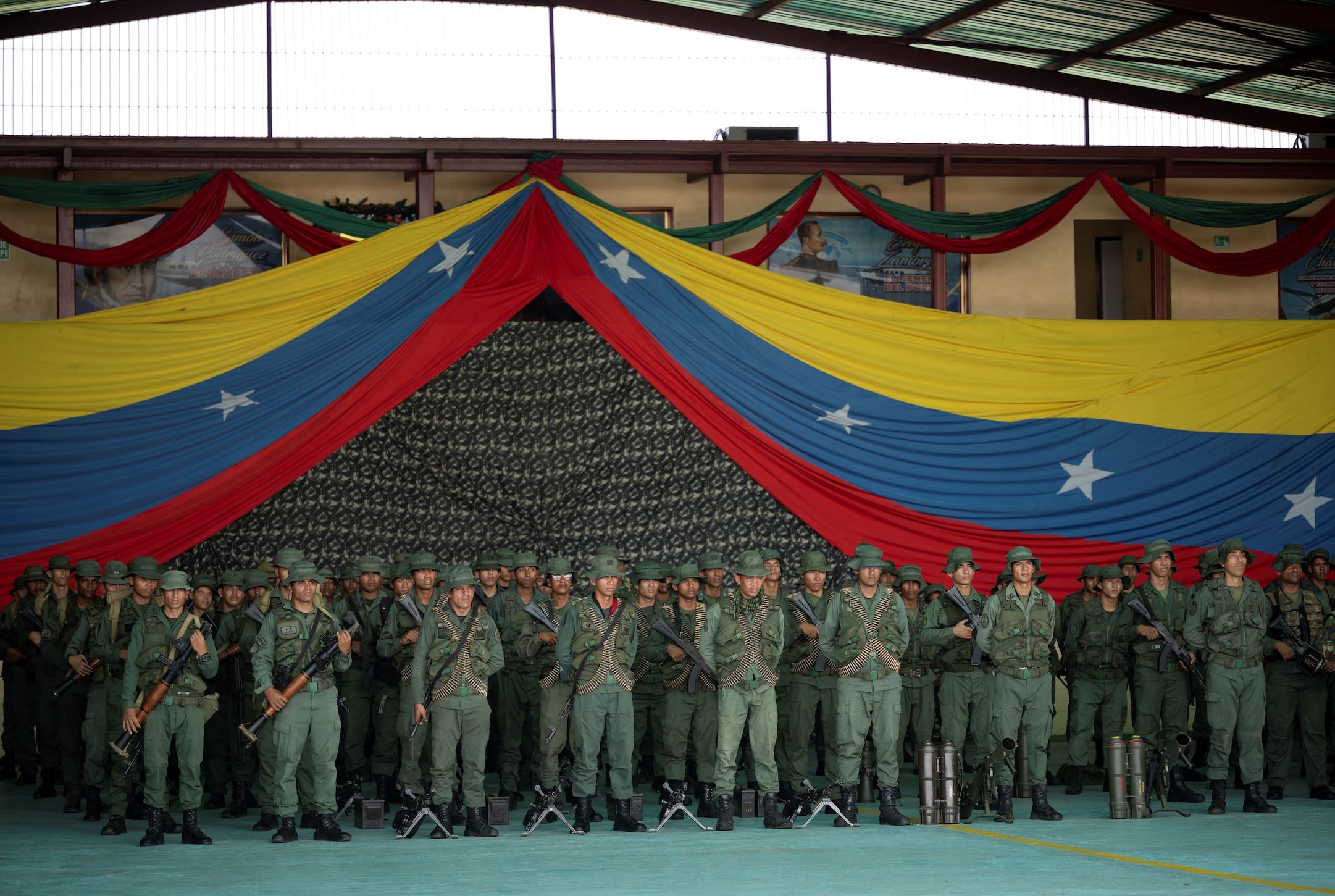

Non-state armed groups are significant players in Venezuela’s organized crime.

These groups have control over parts of Venezuela, and as a result the Venezuelan government can no longer enforce laws. This power dynamic results in the protection of these illegal activities, in turn providing access to illegal mining.

For example, the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional), one NSAG, works together with the state and is involved in many instances of illicit activity, including taking cuts from the profit of the illegal gold mining and bribes from illegal miners in the Amazonas in southern Venezuela.

However, sometimes NSAGs appear to crack down on illegal mining. For example, in 2023, the Bolivarian National Armed Forces (Fuerza Armada Nacional Bolivariana, or FANB) pushed out more than 14,000 illegal miners from the Cerro National Park, located in southern Venezuela, in an attempt to crack down on illegal mining sites.

A Bolivarian National Armed Forces female artillery overfly the Yapacana National Park along the Venezuela-Colombia-Brazil border during a military operation against illegal mining. | Yuri Cortez / AFP via Getty Images

A Bolivarian National Armed Forces female artillery overfly the Yapacana National Park along the Venezuela-Colombia-Brazil border during a military operation against illegal mining. | Yuri Cortez / AFP via Getty Images

This action was considered a major step against illegal mining in the area. However, some experts have argued that the FANB’s actions were only a show put on to avoid international pressure to cease illegal mining in the Amazonas state.

According to Cristina Burelli, the director of SOS Orinoco—an organization dedicated to raising awareness to the environmental issues in the Amazonia and Orinoquia regions of Venezuela—illegal mining has not ceased in that area.

This is not the only instance of the Venezuelan government trying to conceal illegal mining activity.

In 2016, Minister of Environmental Mining Development Víctor Cano and Minister of Indigenous Peoples Aloha Núñez met with captains from the Pemón Indigenous tribe located in the southeastern Gran Sabana municipality.

The meeting was meant to give the Pemón an opportunity to express their complaints about environmental risks and the boundaries surrounding the Orinoco Mining Arc, which was designed for unlawful mineral extraction.

According to Cano, the Orinoco Mining Arc was created to enclose mining activity to an area separated from protected land.

However, Minister Cano’s claims were shot down by a report made by a humanitarian group, Kapé-Kapé, that shows that the illegal mining is still spread throughout the land of the Pemón people.

Brazil

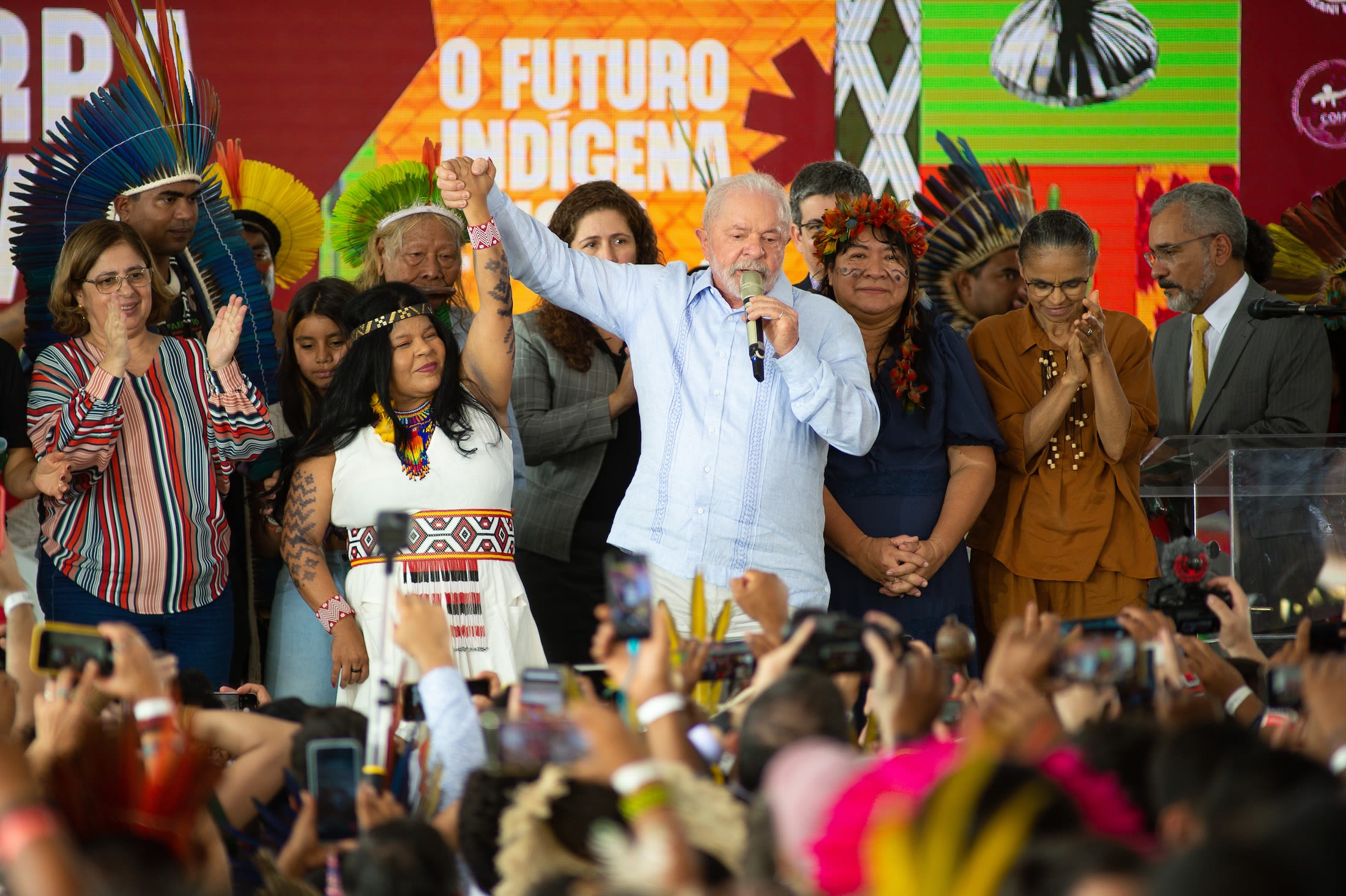

The current Brazilian president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, commonly known as Lula, came into office in January 2023 after defeating Jair Bolsonaro in the 2022 presidential election.

Bolsonaro’s administration did not take action against the high rates of illegal mining in the territories of Indigenous groups, for example, in the Yanomami land.

Following Bolsonaro’s hands-off approach to the issue, Lula made combatting illegal mining a priority, calling for the eradication of illegal gold mining in the Yanomami reserve.

When Lula was initially elected into office, he rapidly called for the eradication of illegal gold mining in the Yanomami reserve, in hopes of driving off the illegal miners in the area.

Some of the initiatives that Lula has implemented to reduce the amount of illegal gold mining in this area include the blocking of supply networks, such as flights or river transport that provide the illegal miners with supplies, and attempting to block off any access to areas not authorized by authorities.

Despite Lula’s prioritization of this issue, not all of his initiatives have been fully resourced. Halfway through 2023, the Brazilian military reduced the number of operations dedicated to combatting illegal mining activity in the Yanomami areas.

The Brazilian air force has not enforced the no-fly zone ordered by Lula, which was intended to prevent unregistered pilots from flying miners into and out of the area.

Alleged illegal miners leave an illegal mining area in Yanomami territory in Roraima state, Brazil. | Michael Dantas / AFP via Getty Images

Alleged illegal miners leave an illegal mining area in Yanomami territory in Roraima state, Brazil. | Michael Dantas / AFP via Getty Images

The Brazilian navy has also not undertaken any substantial action to block off access via the rivers, which are the main conduits for miners to access their machinery and supplies.

However, Lula has continued to emphasize the importance of removing the illegal miners from the territory and has pledged 1.2 billion reais ($245 million) toward security and assistance efforts for the Yanomami tribe.

If sufficient resources are devoted to the problem, the Lula government has the potential to reduce the impacts of illegal mining in the Yanomami region. However, even if the Brazilian government prioritizes the issue, its inability to control what takes place across the border in Venezuela will allow for partial solutions at best.

Moving Forward

The illegal gold mining in Venezuela and Brazil has many effects on the Indigenous communities in both states. Creating solutions to help them is a vital step toward protecting the people and their land, but it is difficult.

When asking the co-founder and co-director of Insight Crime, Steven Dudley, what vital steps must be taken to prevent illegal gold mining, Dudley said, “These areas are run on a combination of some sort of economic desperation and criminal prowess, to be honest . . . and so dealing with those kinds of large forces is extremely difficult, if not impossible.”

While mitigating the effects of illegal mining may seem impossible today, tracking the problem is critical to developing future solutions.

Berg explained that NGOs have been helping to monitor the situation in Indigenous communities: “There are a number of different tests that some NGO groups have been doing to be able to monitor the soil, to be able to monitor the water so that they can try to keep Indigenous communities safe, and also informed.”

Even if immediate solutions are not forthcoming, Berg emphasized that documenting the crisis would hopefully allow for more effective action in the future, as well as accountability for those who have enabled the crisis.

There is also some hope that Lula can use his close relationship with Maduro to push Venezuela’s leader on environmental issues. Lula has positioned himself as a regional leader on environmental issues, hosting a summit in Brazil in 2023 to renew the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization.

While Maduro and Lula have discussed environmental issues, those discussions have not yet yielded much concrete action from the Venezuelan side.

Although Brazil has taken steps toward helping its Indigenous communities recover from illegal mining, more action can still be taken. But many experts have little hope that Venezuela will see any significant progress as long as Maduro’s government, with its close ties to illegal mining, remains in power.

For now, documentation of the effects of illegal mining can be collected in order to hold both governments accountable.

The Indigenous communities in both Brazil and Venezuela have suffered greatly from virtually unchecked illegal mining in recent years. They will continue to pay the price of illegal mining until real efforts are made to address the issue on both sides of the border.

Authors

Special Thanks:

Story: Marla Hiller

Video: Michael Kohler

Audio: David Lotfi

Data: William Taylor

Editorial: Mark Donaldson

Program Support: Sarah B. Grace