Examining Impacts, Capabilities, and Opportunities

A Report by the CSIS Global Development Department

November 13, 2025

This multimedia compendium is organized by topic and forms Part II of our three-part series, A New Landscape for Development, which examines the context, current state, and early impacts of the dramatic changes in priorities, plans, and organizational structures related to U.S. engagement with developing countries. The other parts include:

Part I – The Ground Has Shifted

Part III – Recommendations

Global Health

Since January 2025, the global health sector has faced program eliminations and suspended service delivery amid uncertainty about the future of U.S. efforts. In September, following the announced U.S. withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO), the stop-work order leading to the termination of bilateral health contracts, and the dismantling of USAID, the Department of State released the America First Global Health Strategy. In this video, J. Stephen Morrison and Katherine E. Bliss discuss the strategy’s priorities and prospects for success in the face of the funding cuts and loss of expertise that have shaken the sector.

No program has been more affected by the global health policy shifts than PEPFAR. Over the last two decades, the flagship U.S. HIV/AIDS program has been credited with saving more than 25 million lives and preventing nearly 8 million children from being infected with HIV at birth. Through bilateral programs in high-burden HIV countries, as well as a partnership with the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, PEPFAR was poised in 2025 to advance the delivery of HIV prevention, diagnostic, and treatment services to millions via technical assistance; the provision of essential commodities; and training for healthcare and laboratory workers. By August of 2025, however, 65 percent of USAID’s bilateral PEPFAR awards had been terminated, with countries such as Malawi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, and Zimbabwe seeing 25 to 50 percent of programs cut, and South Africa more than 75 percent. With the closure of USAID missions in many countries, ensuring oversight of funds and monitoring the progress of remaining initiatives will be challenging.

The new U.S. strategy envisions a foreign assistance paradigm that saves lives, supports healthcare workers, and delivers commodities overseas while creating markets for U.S.-innovated products. In it, PEPFAR serves as an anchor for outbreak prevention and response, as well as data collection, supporting countries’ health systems as they are transitioned to local management. The new strategy also proposes an integrated planning process that will bring HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, polio, and global health security together, while requiring recipient governments to cofinance programs. However, it remains to be seen how expanding access to new products, integrating disease programs, responding to outbreaks, and managing cofinancing will unfold against the backdrop of a limited U.S.-WHO relationship, downsized diplomatic engagement, and reduced resources for global health.

J. Stephen Morrison, Senior Vice President and Director, Global Health Policy Center

Katherine E. Bliss, Director and Senior Fellow, Immunizations and Health Systems Resilience, Global Health Policy Center

Humanitarian Aid, Disaster Response, and Resilience

The United States’ capabilities and resources for international humanitarian aid, disaster response, and resilience support have undergone unprecedented change since the start of the second Trump administration. Major cuts to staffing and budgets have impacted the government’s ability to support developing country partners in the face of mounting crises and extreme weather catastrophes. Indicative of the direction the administration has already set through its actions in FY 2025, its FY 2026 budget request represents a 79 percent decrease in Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPs) funding compared to 2025 enacted levels. The elimination of USAID fundamentally transformed what had been that agency’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance and Bureau for Resilience, Environment, and Food Security. A standing capability for humanitarian crisis response that consisted of over 1,000 highly trained staff and $10 billion in funding has been reduced to a staff of fewer than 50 and embedded within the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. Meanwhile, much of the infrastructure and talent that enabled the United States to partner with communities and countries to bolster their underlying resilience has been dismantled despite mounting physical risks from disasters stemming from natural hazards. The closure of USAID operations and missions abroad has stopped risk reduction efforts and crippled U.S. rapid response to disasters. The lack of a robust system of disaster response teams in key areas means that it now takes days or weeks, instead of hours, for assistance to be delivered, if it is to be delivered at all.

As humanitarian crises and extreme weather events persist and grow, it is still often in the U.S. interest—reputationally, economically, and strategically—to help developing countries anticipate challenges and recover from shocks. Rather than over-relying on reaction, the United States will have to consider cost-effective approaches that are ready for scale, including support for pre-arranged disaster risk finance measures that leverage market forces and public-private partnerships.

In this brief analysis and an associated video presentation on the potential to better leverage insurance, Noam Unger delves deeper into some of the issues around humanitarian aid, disaster response, and resilience.

Learn more about this topic here and here.

Noam Unger, Vice President, Global Development Department,

Director, Sustainable Development and Resilience Initiative and Senior Fellow, Project on Prosperity and Development

Economic Growth Assistance

$11 billion

The approximate amount the United States spent on economic development activities abroad, constituting about 13 percent of total foreign assistance. Due to the sweeping changes, that number could drop by 30 to 40 percent in 2025.

The United States engages in economic growth programs abroad to strengthen the foundation of other countries' market economies. These programs include activities such as expanding access to energy and infrastructure, building a skilled workforce, improving the productivity of agriculture and industry, and supporting legal and regulatory reforms. The goal of these activities is to promote economic stability abroad and increase the income levels in partner countries, while protecting U.S. national security interests and promoting commercial opportunities for American firms.

These programs and activities are supported through bilateral and multilateral channels using a mix of financing instruments: grants, loans, guarantees, equity investments, and technical assistance and training, among others.

U.S. bilateral capabilities on economic growth are shifting, and there is still a high degree of uncertainty as to which agencies will remain and take the lead. USAID, which provided significant technical assistance in this space, has been administratively abolished. The Trump administration also eliminated funding for several smaller U.S. government organizations involved in international economic growth work, including the Inter-American Foundation and the U.S. African Development Foundation. The administration has proposed a single “America First Opportunity Fund” (A1OF) of $2.9 billion. The new A1OF would be managed as a flexible fund by the State Department for priorities that advance U.S. national interests. Moreover, various bilateral agencies that promote economic development abroad still remain, presenting an opportunity to collaborate more closely and modernize U.S. capabilities. This unsettled moment presents an opportunity to build a new strategy and framework for U.S. economic engagement in developing countries, through partnerships grounded in mutual benefit.

In this paper, Romina Bandura makes the case that bilateral U.S. economic growth efforts abroad should align with early-stage investment models and focus on three broad goals: promoting prosperity and economic self-reliance in developing countries, creating commercial opportunities for U.S. firms, and protecting U.S. national security interests.

Learn more about this topic here.

Romina Bandura, Senior Fellow, Project on Prosperity and Development

Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance

While the Trump administration dismantled USAID and much of the wider foreign assistance ecosystem, democracy, human rights, and governance (DRG) programming and approaches were addressed with particular enmity. The sector saw a nearly 75 percent cut in budgetary obligations between FY 2024 and FY 2025, and the administration has called into question the merits of democracy promotion work, positing that these activities “undermine American values” and “interfere with the sovereignty of other countries” while describing the programming as “regime change,” a categorization that has already been cited in investigations of USAID partners. These designations make it difficult to envision that there will be any meaningful return to DRG work as the administration considers the future of foreign assistance.

DRG assistance across government agencies necessarily encompassed a broad range of efforts aimed at democracy building, the promotion of good governance, and the protection of human rights. This included support to countries holding elections as well as support to civil society groups monitoring those elections for fairness and conduct. U.S. DRG assistance further supported governments working to improve the functioning of their courts and other dispute resolution mechanisms, as well as civil society groups using those courts to protect the human rights of citizens against government overreach. Vitally, it also provided support for civil society groups operating under closing civic space or tyrannical governments.

Proponents of DRG work emphasize not only its normative value and importance for peace, security, and economic growth, but also its role in ensuring the sustainability of other development efforts. Health assistance is vital in preventing the global spread of disease, but it cannot be sustained without the capacity building of civil society organizations and the development of health systems that ensure such efforts will continue beyond individual programs. Humanitarian assistance saves lives, but without efforts to promote good governance, peace, and security, the need for such assistance will only grow. A future without such DRG work is a future where other development work is unsustainable.

In this commentary, Andrew Friedman and Anne Frederick examine the impacts of cuts to democracy, human rights, and governance funding to the future of development across all sectors.

Learn more about this topic here.

Andrew Friedman, Senior Fellow, Human Rights Initiative

Anne Frederick, Program Manager, Human Rights Initiative

Global Food and Water Security

The second Trump administration has brought significant uncertainty to global food and water security—two pillars of U.S. international engagement that have traditionally experienced strong bipartisan support from policymakers. Beginning in January 2025, stop-work orders effectively froze activities across core U.S. foreign assistance programs. The administration’s dismantling of USAID and transfer of responsibilities to other government agencies has further disrupted coordination and oversight.

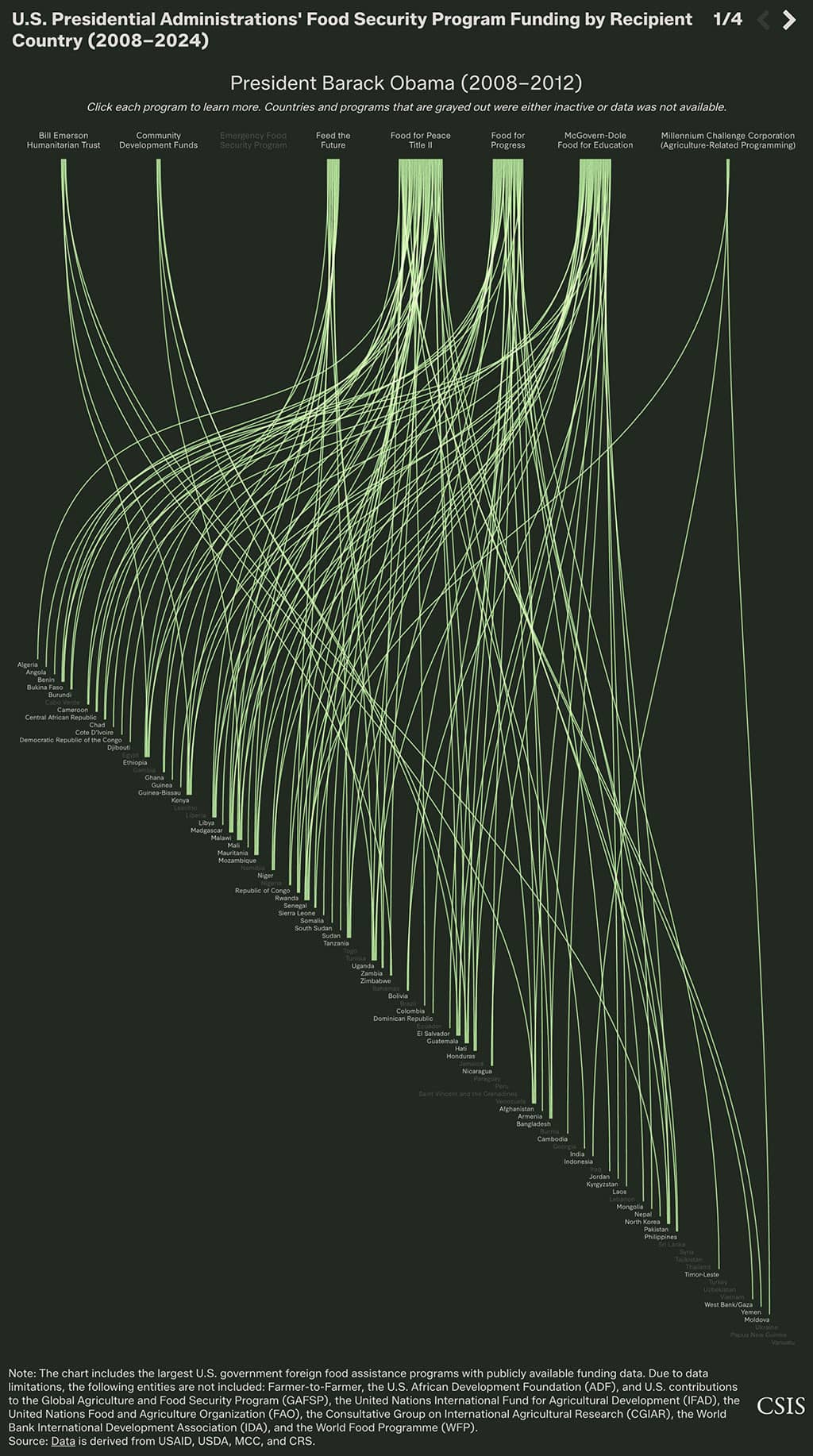

Global food security uncertainty deepened on May 2, 2025, when the Trump administration’s FY 2026 budget request proposed major cuts to or eliminations of the McGovern-Dole, Food for Progress, and Food for Peace Title II programs, among others. Prior to these changes, the U.S. government was the world’s largest donor to food security efforts. Over the past several decades, U.S. foreign food assistance has evolved from surplus commodity shipments to a complex network of programs combining surplus commodity shipments, technical assistance, local and regional procurement, agricultural investments, food vouchers, market-based aid, and direct food distribution to provide both emergency and non-emergency support. Core programs were administered through a wide range of agencies, funding streams, and legislative mandates—all of which are now in flux.

Global water security efforts have faced a similarly destabilizing trajectory throughout 2025. The U.S. Global Water Strategy—a whole-of-government approach across 14 agencies—lost much of its existing architecture, leaving thousands of projects halted mid-implementation or eliminated outright. Budget cuts, staffing reductions, and the shuffling of institutional roles and responsibilities threaten to undermine the Global Water Strategy’s four key objectives.

In 2025, policy disruptions have substantially degraded U.S. capabilities to realize comprehensive and scalable solutions; engage and enhance local leadership; strengthen resilient economies; bolster stability and security; and increase policy integration across humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding objectives. Moving into FY 2026, the U.S. government’s foreign food and water security capabilities will depend on the results of ongoing congressional negotiations over appropriations bills and the emerging priorities of the Trump administration.

Through an infographic, Caitlin Welsh, Rose Parker, and Joely Virzi map out the past and current architecture of U.S. foreign food assistance, while David Michel delves deeper into the sweeping changes to global water security through a commentary.

Learn more about this topic here.

Caitlin Welsh, Director, Global Food and Water Security Program

David Michel, Senior Fellow, Global Food and Water Security Program

Rose Parker, Program Manager, Global Food and Water Security Program

Joely Virzi, Program Coordinator and Research Assistant, Global Food and Water Security Program

Global Youth Engagement

The Trump administration’s dismantling of USAID has resulted in the suspension of all youth-related programming the agency had been spearheading. Since then, 396 education programs in 58 countries have been abruptly halted. Alongside its education programming, USAID invested approximately $296 million in its Youth Development Policy in FY 2023, reaching 7.3 million children and youth and equipping 1.3 million youth with management, leadership, social, or civic engagement skills in 2023. While much of the focus in recent months has been on life-saving programming, it is critical to be clear eyed about the long-term implications of the United States stepping back from funding youth-led development around the world.

USAID youth programming encompassed a broad range of efforts, including education, workforce development, entrepreneurship, support for technical and vocational training, life skills training, well-being resources, and access to economic opportunities. A majority of USAID education funding focused on the Middle East, North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa. The goal of these programs was to build a youth population across the world that had access to quality education, was civically engaged, and was equipped with the necessary skills to enter the job market. USAID reported that in 2021 alone, 71 percent of youth participants went on to engage in civil society activities following skills training programming. The recent disruptions have led to fewer young people in trainings, reduced civic engagement, and increased youth unemployment.

While young people represent a great opportunity for their countries’ economies and global standing, high youth unemployment rates, combined with the retreat of USAID programming, present clear risks. The world is experiencing a serious youth bulge. Presently, young people (ages 15–24) account for 16 percent of the global population, and Africa is the youngest continent, with 60 percent of its population under the age of 25. Across the world, young people, particularly members of Gen Z, have been a critical asset in standing up to corrupt and repressive regimes. On the one hand, the loss of youth-targeted programming creates a significant gap in the development agenda and poses real threats to countries’ stability and economic growth. On the other hand, this shift in U.S. engagement misses the opportunity to connect constructively with youth around the world and leaves a gap for other countries and donors.

In response to a set of critical questions, Hadeil Ali examines the impacts of USAID youth programming cuts on the future of global development.

Learn more about this topic here.

Hadeil Ali, Chief of Staff, Global Development Department

Visit Recommendations to learn about

impactful engagement in the changed landscape.

Recommendations

This report is made possible by general support to CSIS.

No direct sponsorship contributed to this report.

Editors

Noam Unger, Andrew Friedman, & Hadeil Ali

Acknowledgements

Veronica McIntire, Joely Virzi, & Sophia Hirshfield

Photo Credits

Cover: A man plucks saffron flowers during harvest season in Pampore area of Srinagar, Indian Administered Kashmir on 05 November 2023. | Muzamil Mattoo/NurPhoto via Getty Images. Global Health: A Kenyan health worker prepares to administer a dose of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine to her colleagues, part of the COVAX mechanism by GAVI , to help fight against coronavirus disease at the Kenyatta National Hospital in Nairobi on March 05, 2021. | Simon Maina /AFP via Getty Images. Humanitarian Aid: Volunteers and rescue teams search a destroyed building on February 12, 2023 in Adiyaman, Turkey. | Chris McGrath/Getty Images. Economic Growth: Workers fit electrical system cabling to the interior of a BMW 3 Series automobile as it passes along the production line at the Bayerische Motoren Werke (BMW) AG plant in Rosslyn, South Africa, on Wednesday, Sept. 9, 2015. | Kevin Sutherland/Bloomberg via Getty Images. Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance: Tens of thousands of supporters gather at Heroes' Square as opposition leader Peter Magyar of the Tisza Party addresses the crowd during a 'peace march' in Budapest, Hungary, on October 23, 2025. | Robert Nemeti/Anadolu via Getty Images. Global Food and Water Security: Traders and locals gather at a wholesale fish market in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on August 25, 2025. | Syed Mahamudur Rahman/NurPhoto via Getty Images. Global Youth Engagement: Young people, living in Mathare slum, learn future technologies at a robotics and coding workshop in Nairobi, Kenya on May 11, 2023. | Gerald Anderson/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Recommendations: Chinese fishing nets Kochi Kerala India at sunset. | David Hastilow via Getty Images

Story Production

The Andreas C. Dracopoulos iDeas Lab:

Design by: Gina Kim & Sarah B. Grace

Project management by: Sarah B. Grace

Video by: Shawn Fok & David Lotfi

Development by: José Romero & Mariel de la Garza

Editorial support by: Phillip Meylan, Hunter Hallman, Kelsey Hartman, & Madison Bruno

Data visualization by: William Taylor