Bridging the Gap in Immunizations

& Health Services for Venezuelans

at Home & Abroad

Venezuela was once internationally recognized for its achievements in disease control and improvements in the quality of healthcare.

By the 1950s, Venezuela’s years of effort focused on addressing infectious disease and increasing life expectancy had paid off for much of the population. But not everyone benefited equally from these changes, and the rural and urban poor alike remained marginalized from health services and vulnerable to deadly outbreaks.

It was under the leadership of Hugo Chávez (1998–2013), and in alignment with the socialist goals of his Bolivarian Revolution, that Venezuela sought to remedy this. The Chávez government worked to ensure more equitable access to healthcare through a new constitution that guaranteed citizens the right to health.

Funds from the petroleum sector, the backbone of the Venezuelan economy, financed new healthcare facilities and programs intended to extend services to all sectors of the population.

Through Misión Barrio Adentro (“inside the neighborhood”) the government placed doctors, many of them from long-time ally Cuba, in the most impoverished settings, with a goal of ensuring all Venezuelans could benefit from lifesaving medical treatment.

But after several years of progressive improvements in life expectancy, the situation in the health sector began to deteriorate. Heavy blows to public investment in health and other social services were dealt by fluctuating oil prices, the death of Chávez in 2013, Nicolás Maduro’s election as president, and faltering oil production due to mismanagement.

A hospital ward in Caracas, Venezuela, circa 1955. | Jack Manning/Three Lions/Getty Images

A hospital ward in Caracas, Venezuela, circa 1955. | Jack Manning/Three Lions/Getty Images

A hospital ward in Caracas, Venezuela, circa 1955. | Jack Manning/Three Lions/Getty Images

A hospital ward in Caracas, Venezuela, circa 1955. | Jack Manning/Three Lions/Getty Images

Patients wait to be seen by doctors of the "Barrio Adentro" program in west Caracas in 2005. | Andrew Alvarez/AFP via Getty Images

Patients wait to be seen by doctors of the "Barrio Adentro" program in west Caracas in 2005. | Andrew Alvarez/AFP via Getty Images

Venezuela soon saw rising rates of maternal mortality and child death. Outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases such as diphtheria and measles increased as immunization rates fell.

As the government resorted to the use of force and censorship to suppress protests or prevent information about the internal situation from being publicized, it also stopped reporting basic health indicators to many international organizations.

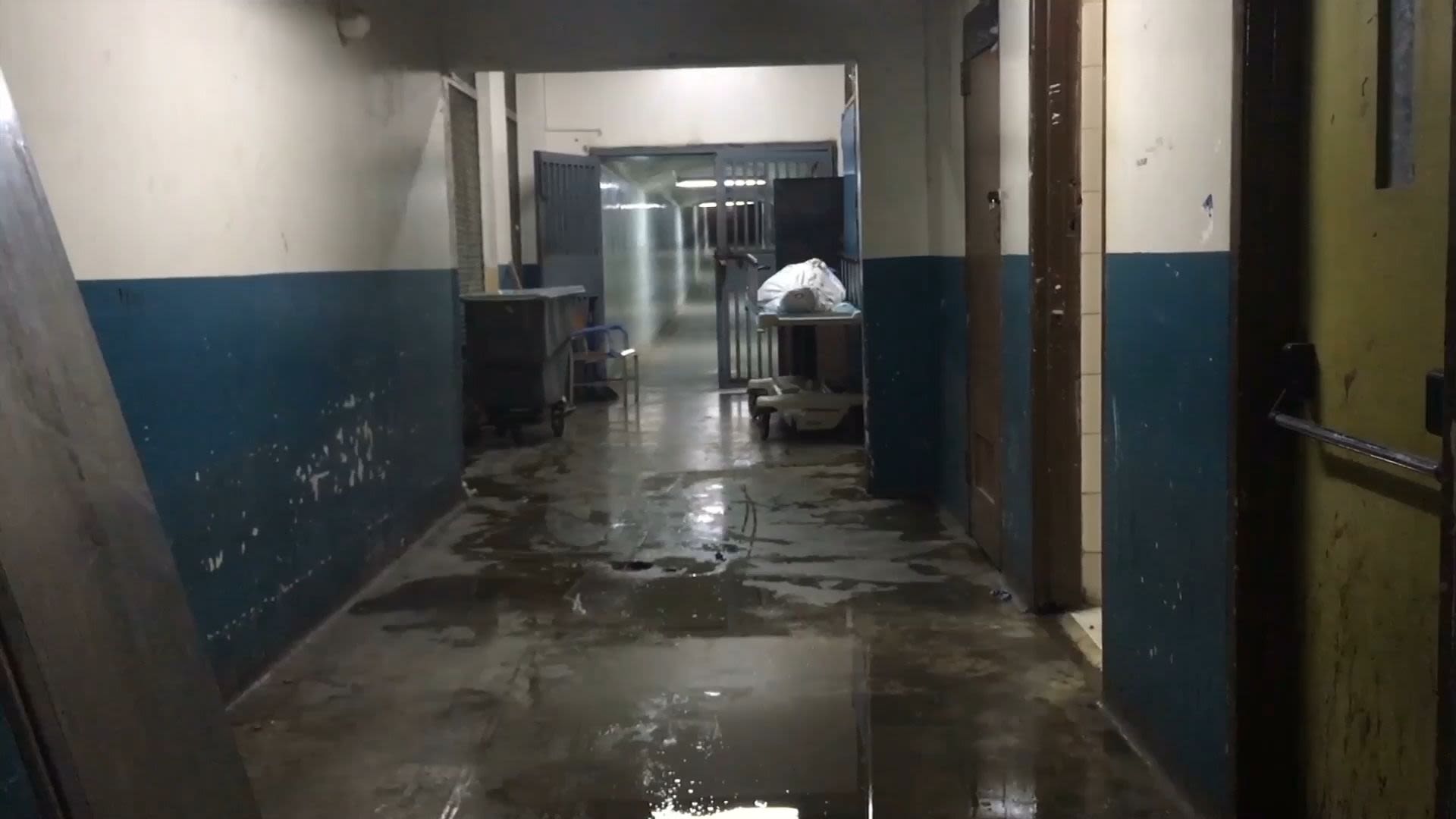

However, news stories and photographs have documented hospitals without running water or electricity and pharmacies with shelves empty of medicines such as antiretrovirals for patients living with HIV, antimalarial drugs, or chemotherapy for cancer patients.

These developments pointed to the possibility that many of Venezuela’s healthcare achievements of the last half century would come unraveled, with negative health security implications for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Then, in March 2020, when many thought the situation in Venezuela’s healthcare sector could not get much worse, the first cases of Covid-19 in the country were reported.

Covid-19 in Venezuela

On March 13, 2020, just two days after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the outbreak of the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, constituted a global pandemic, Venezuela reported the first two cases in the country.

To limit further introduction or transmission of the virus, the Maduro administration quickly closed schools, suspended flights, and announced a series of lockdown measures. As curfew plans took shape, Venezuelans, who were already facing challenges from hyperinflation and food insecurity, saw their livelihoods and income-generating prospects disappear.

A masked boy looks out at Caracas in March 2020. | Carlos Becerra/Getty Images

A masked boy looks out at Caracas in March 2020. | Carlos Becerra/Getty Images

The lack of water and sanitation in clinics as well as residential areas raised concerns about people’s ability to prevent disease transmission, while the dilapidated state of health facilities suggested it would be challenging for many to access adequate care, if needed.

Experts worried that this combination of factors could transform the existing health crisis into a full-blown catastrophe.

It may never be possible to know just how severely the pandemic has affected Venezuela.

Limited testing and many government officials’ unwillingness to share information about health conditions in the country have complicated efforts to generate reasonable estimates of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths due to coronavirus infections.

Compared to neighboring countries, Venezuela’s confirmed Covid-19 cases and deaths appear surprisingly low. In July 2020, when South America was the epicenter of the pandemic, Venezuela reported a seven-day average of just 18 cases per million people. This contrasted starkly with its neighbors—Brazil reported more than 210 cases per million, and Colombia reported 143 cases per million people.

Even now, more than two years later, Venezuela reports a cumulative total of just 544,450 confirmed Covid-19 cases, as of September 26, 2022. It has reported only 5,814 deaths, or 206 deaths per million people.

The fact that Venezuela’s numbers are significantly lower than its neighbors is almost certainly due to undercounting. Guyana reported 1,592 deaths per million people, Colombia reported 2,752 per million, and Brazil reported 3,200 per million.

Venezuela has been distributing Covid-19 vaccines since they became available in late 2020. In early 2021, the government began providing vaccines produced by Russia, China, and Cuba. The first shipment of more than 10 million vaccines from COVAX, the global vaccine distribution program, was delivered in September 2021.

While officially more than 37 million doses have been administered, only 51 percent of the eligible Venezuelan population had received the complete initial vaccination protocol by February 2022, when the government stopped reporting the number of Covid-19 vaccine doses distributed.

Covid-19 vaccination coverage is lower in Venezuela than in other neighboring countries.

At 51 percent, Venezuela's coverage contrasts with that in Brazil, where 80 percent of the population has completed the full vaccine series, and in Colombia, where more than 70 percent of the population is fully vaccinated.

Given the potential for the emergence of new and potentially more transmissible coronavirus variants, persistent, low Covid-19 vaccine coverage in Venezuela could signal the population’s greater susceptibility to future waves of the virus.

Routine Immunizations in Venezuela

Venezuela’s challenges in scaling up access to Covid-19 vaccines come as little surprise. The country’s routine immunization coverage is among the lowest in the Americas, a region that itself has seen backsliding after years of strong performance.

In 2017, Venezuela’s low immunization coverage contributed to outbreaks of diphtheria and measles, which spread to neighboring countries.

These outbreaks led the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the regional arm of the WHO, to support the Ministry of Health in conducting specialized vaccination campaigns to help nearly 9 million children “catch up” on missed vaccine doses.

However, after two and a half years of Covid-19 challenges, the latest WHO and UNICEF data show that Venezuela’s routine immunization coverage remains quite low. Just 56 percent of children have completed the recommended three doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP) vaccines, and only 68 percent have received one dose of measles vaccine.

Measles and DTP vaccination coverage data are often used as indicators of children’s access to health systems during the first few years of life.

Between the low coverage of Covid-19 vaccines for adults and low levels of access to routine immunizations for children, it can be inferred that a significant proportion of the Venezuelan population has very limited access to health services.

Barriers to Outside Help

Widespread reporting on the challenges facing Venezuela’s public health sector over the past decade has raised awareness about what many organizations have described as a humanitarian crisis.

Venezuela has seen decreased life expectancy, high rates of maternal and child death, stockouts of essential medicines, and dilapidated health infrastructure. Many countries experiencing even one of these crises would enthusiastically accept offers of support from neighbors or others in the international community.

Venezuela has indeed accepted support in the form of medical supplies and, more recently, Covid-19 vaccines from allies and long-time creditors such as Cuba, China, and Russia.

And several United Nations agencies, including UNICEF and PAHO, operate in Venezuela, offering guidance and technical support to government health and social service agencies.

However, the Maduro administration has been less enthusiastic about accepting assistance from other countries or international NGOs. Maduro has repeatedly rejected the idea that the nation is experiencing emergency conditions, calling offers of help “an excuse to intervene” in Venezuela.

The government’s receptivity to engagement by international NGOs since then has been mixed. The Maduro regime remains concerned that allowing international aid organizations to fully operate in Venezuela could create greater opportunities for the United States and other governments it considers to be hostile to the government’s interests to influence the Venezuelan people.

The United States reports that it has provided at least $80 million to support NGOs and international organizations in delivering health and programming related to water, sanitation, and hygiene.

Some international NGOs operate in a limited way in the country, alongside Venezuelan organizations, but many more operate in neighboring countries.

These NGOs offer support to Venezuelans who arrive there seeking food, medicine, or a new start.

II. The Journey

For nearly a decade, the people of Venezuela have dealt with hyperinflation, a lack of economic opportunities, political repression, food insecurity, and limited access to health and social services.

Few resources have been provided by the government, restrictions continue on the extent of assistance available from the international community, and there is little indication that any policy changes in favor of greater public spending on health by the Maduro administration are forthcoming.

In light of these realities, many people have made the difficult decision to leave Venezuela.

The diaspora of Venezuelans has been called the “second-largest external displacement crisis” in the world and “the largest migration crisis in Latin American history.”

In September 2022 the UN Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela reported that an estimated 7.1 million Venezuelans worldwide have been classified as refugees, migrants or asylum-seekers by host governments.

Most Venezuelans have left to find work and better livelihoods in neighboring countries, such as Colombia, Peru, and Brazil.

Others have moved farther away to the United States, Canada, and Spain.

Whether joining family members who have already left or striking out on their own, Venezuelans who leave their country face considerable challenges, both on the journey and upon reaching their final destinations.

For those for whom a plane ticket is unaffordable or impractical, an overland journey is the best option among many difficult choices.

The first stop for the majority of those leaving Venezuela this way is undertaking a journey through neighboring Colombia.

The Journey to Colombia

A 1,380-mile border separates Venezuela (right) from Colombia (left). The migration journey between the two countries is difficult and sometimes treacherous.

Nearly two-thirds of Venezuelans who leave attempt to cross informally, walking hundreds of miles through dry conditions and intense heat in their quest to reach unofficial and unprotected sections of the border.

Those who cannot afford to pay a smuggler to help them get across safely may face armed groups that operate near the border. These groups control the most practical crossing points and demand money or other concessions to allow people to cross into Colombia.

Formal border posts pose a different set of challenges. At these official border crossings, people leaving Venezuela must contend with the military, which, under Maduro, controls border operations. Military officers working at border posts frequently demand money from people wishing to leave the country to compensate for their own low salaries.

One of the most frequent crossing sites is the Puente Internacional Simón Bolívar. This iconic bridge spans the Táchira River, joining San Antonio del Táchira in Venezuela with the community of La Parada on the outskirts of Cúcuta in Colombia.

The people who travel for hundreds or thousands of kilometers to reach this bridge are known as los caminantes (“the walkers”).

The Puente

The Puente Internacional Simón Bolívar once stood as symbol of democracy and regional integration.

The Simón Bolívar International Bridge between Colombia and Venezuela is situated in the northernmost stretch of the Andes Mountains. | CSIS

The Simón Bolívar International Bridge between Colombia and Venezuela is situated in the northernmost stretch of the Andes Mountains. | CSIS

Inaugurated in 1962, the bridge was considered “the most dynamic frontier in Latin America.”

It enabled people from Venezuela and Colombia to easily cross back and forth between the countries for shopping or other day-trip activities.

Use the slider on the image below to see key features of normal bridge operations in 2014.

Crossing the bridge between the two countries is no longer so simple.

As economic conditions in Venezuela worsened in 2014, Maduro began periodically closing the Simón Bolívar bridge.

The justification was that closing the bridge would stem the flow of contraband, including medical supplies, into Venezuela by alleged bachaqueros (“black-marketeers”). It was a way to stop Venezuelans from smuggling Venezuelan gas into Colombia to sell on the black market, as well.

Maduro then issued a state of emergency in five municipalities bordering the bridge, closing it from 2015 to 2016.

On July 16, 2016, the border reopened briefly, allowing 35,000 Venezuelans to cross into Colombia in search of food and medicine that day.

The following day another 88,000 people crossed the bridge in hopes of finding similar relief.

The Colombian and Venezuelan authorities subsequently agreed to gradually reopen Puente Internacional Simón Bolívar between 5 a.m. and 8 p.m. in 2016.

For the next two years, the bridge remained open on a regular basis, allowing safe formal passage into Colombia for millions of Venezuelans.

Following widely disputed elections in 2018, in which Maduro claimed victory, the United States and other countries recognized Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó as interim president. In February 2019, Guaidó arranged for several tons of medical supplies to be delivered to Venezuela from across the border in Colombia.

However, the Venezuelan military, which oversees ports and border crossings, refused to allow the goods to cross into the country and opened fire on the trucks.

Bilateral relations between Colombia and Venezuela eventually eroded.

The border remained closed during the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Use the slider on the image below to see key features of the bridge when all traffic was barred in 2020.

Colombia eventually opened its side in June 2021, but Venezuela did not allow passage across the bridge until October 2021.

As seen in the most recent satellite image from January 6, 2022, the bridge is currently only open to pedestrian traffic.

Use the slider on the image below to see key features of the bridge with traffic restricted to pedestrians in 2022.

This is reportedly because its structural integrity must be reassessed after many years of inactive use and lack of maintenance.

III. In Colombia

Many Venezuelans make the journey to Colombia with what little they can carry on their backs, in hopes of restarting entirely when they get there.

By October of 2022, nearly 2.5 million Venezuelans were living in Colombia, according to the Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela.

But while Colombia offers more opportunities than Venezuela, many displaced Venezuelans find themselves in precarious situations after crossing the border.

Formal work can be hard for Venezuelans to find, leaving many without a reliable income, access to housing, or regular meals.

At least 75 percent of Venezuelans displaced in Colombia are believed to work in the informal sector, where they face harsh labor conditions, sexual exploitation, extortion by police, and recruitment by criminal organizations.

Venezuelans displaced abroad also face stigma and xenophobia, with one survey conducted early in the pandemic showing that nearly 70 percent of Colombians held unfavorable views of Venezuelans.

Securing legal and protected status in Colombia has been difficult for many.

It was only in 2021 that Colombia authorized a temporary protection status (Estatuto Temporal de Protección para Migrantes Venezolanos) for Venezuelans living in the country. Even this only authorizes them to stay in Colombia for 10 years.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), forcibly displaced people include refugees, asylum-seekers, internally displaced people, and Venezuelans displaced abroad. It includes refugees and other displaced people not covered by UNHCR’s mandate and excludes other categories such as returnees and non-displaced stateless people.

Ninety-six percent of Venezuelans displaced in Colombia (2.4 million people) have applied for the protection permit.

As of July 2022, it has been granted to 1.4 million people, giving them access to healthcare, education programs, and other social services.

However, receiving the permit to live and work in Colombia does not guarantee Venezuelans full-time employment or reliable housing.

Covid-19 also worsened the challenges Venezuelans who had moved to Colombia already faced.

When the pandemic hit, many shelters that had housed Venezuelans closed.

Informal work became harder to find due to lockdowns, and deportations intensified.

Venezuelans displaced in Colombia also faced increased discrimination because of the widespread fear that they were infected with and were spreading coronavirus.

Covid-19 in Colombia

Since undertaking health sector reforms in the 1990s, Colombia has made significant progress toward universal health coverage. Impressively, nearly 97 percent of the population has some form of health insurance, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

While Colombians may enjoy greater access to healthcare than people living in Venezuela, Colombia has had its own challenges with Covid-19.

As of September 26, 2022, nearly 142,000 people in Colombia had died as a result of Covid-19, and there have been more than 6 million confirmed cases.

The pandemic has led to significant unrest in Colombia.

In the spring of 2021, when the death rate from Covid-19 reached 700 people per day, popular frustration with lockdowns, tax reforms, economic inequality, and police brutality led to a series of protests and deadly strikes in cities across the country.

A protester in Bogotá, Colombia, shouts slogans during a march to protest against the measures adopted by the Colombian government to fight the Covid-19 pandemic in April 2021. | Raul Arboleda/AFP via Getty Images

A protester in Bogotá, Colombia, shouts slogans during a march to protest against the measures adopted by the Colombian government to fight the Covid-19 pandemic in April 2021. | Raul Arboleda/AFP via Getty Images

In 2020, Colombia joined COVAX, the international vaccine distribution facility. It purchased 77 million doses through COVAX, while receiving an additional 15 million donated vaccines.

The government has approved six vaccines for use and hosted clinical trials for several products as well. To date, more than 70 percent of the population is considered to be fully immunized with the required doses of the shots.

But even for Colombian citizens, access to health services for some remains a challenge.

Although a peace accord to end Colombia’s decades-long civil war was signed in 2016, not all groups have demilitarized, and the country is still considered to have a series of ongoing conflicts.

Health workers face violence, and health facilities have been subject to attacks. Despite the country’s high rate of health coverage, Colombians who are internally displaced because of these conflicts have had trouble accessing vaccines.

Healthcare for Migrants and Displaced People in Colombia

Migrants living in Colombia, as well as displaced Venezuelans, also face many unique challenges in accessing immunizations and more general healthcare services.

National policies are ambiguous regarding migrant access to health services. Migrants’ lack of awareness regarding their rights with respect to health services in a new context also present significant challenges, as does uncertainty on the part of migrants and their families about where to go to access vaccines.

Refugees include individuals recognized under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, its 1967 Protocol, the 1969 Organization of African Unity (OAU) Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, the refugee definition contained in the 1984 Cartagena Declaration on Refugees as incorporated into national laws, those recognized in accordance with the UNHCR Statute, individuals granted complementary forms of protection, and those enjoying temporary protection.

Asylum seekers are individuals who have sought international protection and whose claims for refugee status have not yet been determined.

Venezuelans displaced abroad refers to people of Venezuelan origin who are likely to be in need of international protection under the criteria contained in the Cartagena Declaration, but who have not applied for asylum in the country in which they are present.

While it can be challenging for non-citizens to access healthcare, it is vitally important to ensure migrants have access to vaccines and other health services.

This not only prevents disease outbreaks but also enables migrants to find work and settle into their new context. Covid-19 has thrown the urgency of this access into stark relief.

A Venezuelan woman wearing a mask emerges from her tent in Bogotá, Colombia, in June 2020. | Guillermo Legaria/Getty Images

A Venezuelan woman wearing a mask emerges from her tent in Bogotá, Colombia, in June 2020. | Guillermo Legaria/Getty Images

Prior to the pandemic, Colombia provided Venezuelans with no-cost emergency services at public facilities. However, the government did not provide non-emergency care to migrants and refugees from across the border. Support from PAHO and other international organizations allowed Colombia to provide migrants with some vaccines, mental health services, and primary healthcare services at several border crossing points.

Since Covid-19 vaccines became available in late 2020, the situation for migrants in Colombia has been mixed.

In December 2020, former president Iván Duque had said that undocumented Venezuelans would not receive Covid-19 vaccines. However, just eight months later, in August 2021, the Ministry of Health authorized the delivery of donated vaccines to people holding the temporary protection permit, as well as those who did not count on government issued identification cards.

A Venezuelan woman receives a Covid-19 vaccine in October 2021 at Colombia's District Center for Integration and Rights of Migrants, Refugees and Returnees in Bogotá. | Raul Arboleda/AFP via Getty Images

A Venezuelan woman receives a Covid-19 vaccine in October 2021 at Colombia's District Center for Integration and Rights of Migrants, Refugees and Returnees in Bogotá. | Raul Arboleda/AFP via Getty Images

But encouraging Venezuelans displaced in Colombia to be vaccinated is another challenge.

Surveys conducted in August and September 2021 among Venezuelans living near the Venezuela-Colombia border suggest that, at least at that time, most were receptive to the idea of vaccination.

However, those who did not have legal documentation were concerned about being able to access the products without risk of deportation or other legal action by the Colombian government.

IV. Moving Forward

An estimated 130,000 Venezuelans who had left their home country have returned since the onset of the pandemic. Challenges finding work abroad or maintaining income during the economic crises many host countries have faced may have prompted them to return home to family and their home communities.

For some, Maduro’s recent economic reforms have opened new opportunities. Oil exports have increased, and inflation has stabilized somewhat. However, the health situation in Venezuela remains dire. Malaria continues to spread, and access to medications for tuberculosis, HIV, and other chronic conditions remains sporadic.

The WHO-UNICEF data for 2021 also show that Venezuela’s DTP coverage remains below 60 percent. This does not bode well for the country’s ability to prevent future outbreaks, whether of diphtheria or other vaccine-preventable diseases.

The board of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, recently approved making Venezuela eligible for access to low-priced vaccines, as well as support for other services meant to strengthen the health and immunization systems. While details about the Gavi-Venezuela relationship are being worked out, this decision could help put the country on a better path toward protecting the population from vaccine-preventable diseases.

Venezuelans at home and abroad are looking forward to the presidential elections in 2024, in which Venezuela’s opposition parties have said they will participate.

It is unclear to what extent the 2024 Venezuelan presidential campaigns will focus on restoring the country’s healthcare system.

Regardless of who holds the power in the future, government efforts to refocus on immunization services, rebuild health facilities, and reinvest in the health system could help bridge the gap between Venezuela’s difficult past and a more hopeful future.

This report was made possible by the generous support of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Authors

- Katherine E. Bliss, Senior Fellow and Director, Immunizations and Health Systems Resilience, Global Health Policy Center

- Mackenzie Burke, Program Coordinator, Global Health Policy Center

Story Production by

CSIS iDeas Lab

- Editorial, production, and video by Sarah Grace.

- Data visualizations by José Romero and Lindsay Urchyk.

- Satellite mapping by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. with markup by Jennifer Jun and William Taylor.

- Maps by Michael Kohler via Mapbox.

- Development support by Christina Hamm.

- Copyediting support by Katherine Stark.

Footage Credits

Title Header Video Grid:

–Top left, top right, middle row, bottom center, bottom right: AFPTV licensed via Getty Images

–Top center, bottom left: Sky News/Film Image Partner licensed via Getty Images

Venezuela Section: Sky News/Film Image Partner licensed via Getty Images

–BBC Motion Gallery Editorial/BBC News licensed via Getty Images

The Journey: International Crisis Group via YouTube under Creative Commons licensing

–AFPTV licensed via Getty Images

In Colombia: AFPTV licensed via Getty Images

–Guillermo Legaria Schweizer/Getty Images

–BBC Motion Gallery Editorial/BBC News licensed via Getty Images

Moving Forward: AFPTV licensed via Getty Images