IMMIGRATION

AND THE UNITED STATES’ INNOVATION DEFICIT

Experts agree that the United States’ semiconductor industry needs to attract and retain global talent in the race for innovation. Why does immigration policy not reflect this consensus?

The rhythms of daily life: turning on the light in the morning, checking the phone, driving to work. Semiconductors are so ubiquitously embedded within everyday objects that these tiny chips’ critical role is frequently overlooked.

However, semiconductors are not just a part of our ordinary routine. They tie all Americans to the highly dynamic and competitive global semiconductor innovation industry.

To secure its competitive lead in this critical technology, the United States must grapple with an increasingly complex immigration system that limits the flow of talent supporting research and development and production within the semiconductor industry. Failing to do so stifles U.S. innovation and risks the country’s competitiveness and national security interests.

Global Chip Competition

A National Security Issue

A robust semiconductor industry is not only integral to domestic manufacturing and production—it is also key to the United States’ global leadership.

“A country’s ability to project power in the international sphere—militarily, economically, and culturally—depends on its ability to innovate faster and better than its competitors,” said Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google, in an article for Foreign Affairs.

Semiconductors are also critical for developing technologies that ensure U.S. security.

“If a potential adversary bests the United States in semiconductors over the long term or suddenly cuts off U.S. access to cutting-edge chips entirely, it could gain the upper hand in every domain of warfare."

The National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence 2021 Final Report

The U.S. government has acknowledged the importance of the semiconductor industry by allocating roughly $53 billion towards the CHIPS and Science Act in 2022. The initiative seeks to reshore manufacturing, expand domestic production, and increase U.S. job opportunities.

To make this significant investment work, the United States needs to draw in skilled foreign workers. Given the complex and high skill intensity required by the semiconductor industry, relying on the current pool of domestic workers alone is insufficient. Ignoring the vital role of foreign talent could curtail the historic potential of the CHIPS Act and leave the U.S. semiconductor industry unable to compete effectively.

Worker Shortage

A 2022 report released by the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) found that 58 percent of necessary manufacturing and design jobs might go unfilled by 2030. SIA projects the following: “Of the unfilled jobs, 39% will be technicians, most of whom will have certificates or two-year degrees; 35% will be engineers with four-year degrees or computer scientists; and 26% will be engineers at the master’s or PhD level.”

“There's a huge semiconductor shortage that's just around the horizon . . . it's a real global competition issue, and it certainly has an impact on how we should take a look at our immigration policy.”

The contributions of foreign workers, particularly highly skilled workers who have been educated and trained in the United States, will be critical to meeting these challenges. The success of the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act and the future of the industry will depend on whether U.S. policies can harness this international talent base.

Closing the Gap

A Critical Talent Base

Talented immigrants from other countries have historically been a driving force for innovation, helping to build the industries that make the U.S. economy flourish.

This is especially true in the semiconductor industry, where scientists and engineers with specialized knowledge are required across the entire supply chain and manufacturing process.

However, as semiconductor manufacturing has increasingly moved offshore over the past few decades, the talent needed to sustain this industry also moved with it. While U.S. consumers benefited from improved products and lower costs, these trends also created a strategic vulnerability for the United States.

Indeed, it took the Covid-19 pandemic, which disrupted global supply chains, to highlight a fundamental problem in the domestic ecosystem supporting the fabrication of semiconductors: a significant dependency on foreign manufacturers for chips that power every aspect of the U.S. economy and national security.

The TSMC facility in Phoenix, Arizona on January 24, 2023. Photo by Caitlin O'Hara for The Washington Post via Getty Images

The TSMC facility in Phoenix, Arizona on January 24, 2023. Photo by Caitlin O'Hara for The Washington Post via Getty Images

As a part of its efforts to reshore chip manufacturing in early 2020, and in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, the U.S. government incentivized the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company to build a chip fab in Phoenix, Arizona.

However, construction was delayed due to a lack of workers with the necessary skills to build complex semiconductor facilities. As a result, around 2,200 Taiwanese workers were flown in to provide their specialized knowledge of building semiconductor plants.

Highly Skilled Workers

While workers with fabrication knowledge are essential, the U.S. semiconductor industry also needs workers to advance innovation to keep its competitive strides in the semiconductor industry.

Highly skilled workers—typically those with PhDs or advanced science and engineering degrees—are essential in pushing forward innovation through their research. This is particularly true for those with specialized knowledge in dynamic STEM industries (e.g., physics, computer science, and engineering). The scarcity of highly skilled workers to meet the demands of semiconductor research and manufacturing requires that the United States attract and retain more foreign STEM talent.

According to a 2021 analysis by Immigration Impact, immigrants made up more than one out of every five (22.7 percent) STEM workers in the country, and almost half of all recent graduates (45.0 percent) from U.S. advanced degree programs were international students.

This means that immigrants make up a significant portion of the potential talent pool for advancing innovation in the U.S semiconductor industry. However, U.S. immigration policies make it hard for international students graduating from U.S. STEM programs to gain employment in the United States, often forcing them to leave to seek jobs elsewhere.

Dr. Sujai Shivakumar, director of the Renewing American Innovation at CSIS, highlights this complex situation facing the domestic semiconductor market.

“The semiconductor industry [includes] everything from research to manufacturing. It is a very science and technology-intensive industry. There is a need for skilled talent to maintain an industry of significant size and scale.”

In order to offset our dependence on chips manufactured abroad and to innovate for future economic growth, urgent reform of the immigration system is needed.

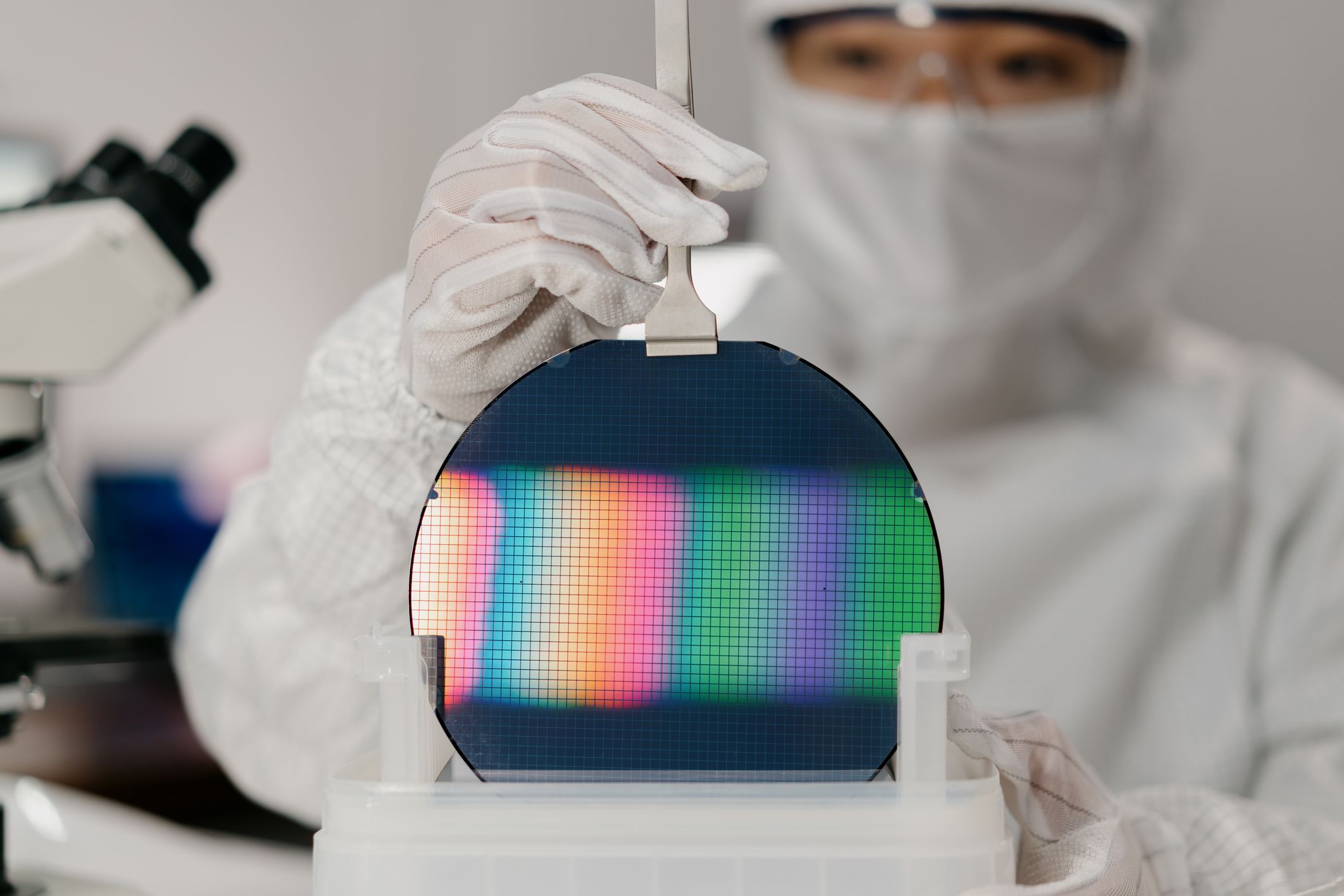

Technicians monitor a machine that manufactures 300 mm silicon wafers at the Applied Materials Inc. Maydan Technology Center in Santa Clara, CA.

Technicians monitor a machine that manufactures 300 mm silicon wafers at the Applied Materials Inc. Maydan Technology Center in Santa Clara, CA.

Obstacles for Immigrants

H-1B Visas

Although the immigration system broadly allows for high-skilled immigrant workers, the capacity of U.S. visa programs to adequately address the current need for highly skilled foreign talent is constrained.

The key mechanism in this regard is the H-1B visa. This visa category allows employers in certain specialized fields to temporarily hire highly-skilled workers from outside the United States. Visas are issued for three years and can be extended to six years at most. Although the H-1B visa is a valuable source of foreign talent, the short-term length can constrain workers’ capabilities to make meaningful long-term contributions.

The process to receive this type of visa is also an intense, arbitrary lottery system. Due to the overwhelming number of applications, this is an additional factor limiting the utilization of foreign talent.

Speakers and Producers: Margot Lang and Isabel McDermott | Featuring: Dr. Sujai Shivakumar, Dr. Charles Wessner, Jaehyun Han

Music: Tom Fox Music Library - Bellingham, Mr. Doe, Speaking Of, Stay Outvia

Excluding exceptional petitions, the maximum number of H-1B visas that can be issued on a yearly basis is 85,000. This number has not been expanded since 2004. In 2025, roughly two decades later, experts recommend that the number of issued H-1B visas be increased to match the semiconductor industry’s exceptional demand for highly skilled workers.

“We don't have enough scholars to do all the work that that we need to do both for a better future for our children, but also for a safer future for the United States.”

A Global Competition for Talent

International competitors increasingly seek to scoop up skilled applicants that the United States fails to authorize. In doing so, they siphon away and retain the expertise of these highly skilled workers, many of whom were trained in the United States.

Marc Miller, minister of Immigration, refugees and citizenship, with 53 new Canadian citizens representing 22 diverse nations, during the Oath of Citizenship special ceremony at Canada Place, on October 12, 2023, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Marc Miller, minister of Immigration, refugees and citizenship, with 53 new Canadian citizens representing 22 diverse nations, during the Oath of Citizenship special ceremony at Canada Place, on October 12, 2023, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

For example, Canada’s highly skilled visa, Express Entry, grants highly skilled foreign talent the ability to work in Canada with the prospect of permanent residence. This policy attracts international talent educated and trained in the United States. According to an analysis by the Niskanen Center, roughly 45,000 U.S.-educated international students left the United States to take jobs in Canada from 2017 to 2021.

Canada especially targets foreign workers in the United States struggling to obtain H-1B visas within tech, such as through their initiative Path to Canada. Canada markets this policy as an “opportunity for foreign-born U.S. graduates to achieve their career goals without the uncertainty of the U.S. visa system.”

A technician inspects the backside of a bitcoin mining rig at Bitfarms in Saint Hyacinthe, Quebec.

A technician inspects the backside of a bitcoin mining rig at Bitfarms in Saint Hyacinthe, Quebec.

Given the current skills requirements created by the resurgence in U.S. semiconductor manufacturing, the United States needs to attract and hold on to STEM talent, who in many cases have benefited from significant U.S. investments in their education and training.

Opening the Door

Expanding Access

Introducing greater flexibility in the H-1B visa program could boost the United States’ talent base, incentivizing and supporting highly skilled foreign workers to stay and contribute to the success of the U.S. semiconductor industry.

“It would be a tragedy to block off a rich source of brainpower for the U.S. economy."

This begs the question:

How can policymakers adjust immigration policies in the United States to make conditions more suitable for retaining international talent?

There is a broad consensus among scholars, which is echoed by large tech companies, that the need for international talent should be reflected in U.S. immigration policy. “We should make it attractive for them and easier for them to come and be more competitive,” said Shivakumar.

A simple suggestion for the retention of international students would be to issue a visa or green card upon graduation. “When you get a doctorate from an American university, it should have a green card stapled to it,” Wessner noted.

As many of these students also receive university funding, adopting this practice would ensure the U.S. industry receives a return on the investments U.S. programs and universities are making.

Immigrants are sworn in as U.S. citizens during naturalization ceremonies in Pomona, California.

Immigrants are sworn in as U.S. citizens during naturalization ceremonies in Pomona, California.

Restructuring the System

Another solution involves adjusting the U.S. H-1B visa lottery system, which has become a bottleneck limiting the retention of highly skilled workers within the country. The current immigration policy awards H-1B visas from a general lottery pool. Although lawsuits have challenged the injustice of pooling all applications into one general lottery, judges have traditionally upheld the simple lottery system as a practical way to process visas given the sheer number of applicants. There is no waitlist.

Rather than pooling all H-1B prospects into one wide pool, visa awards should prioritize high-skilled immigrants who were educated in the United States, reflecting the potential return on investment. Alternatively, visas could be awarded as a percentage of the total, depending on industry and skill-based needs.

Ayah Bdeir, of Lebanon, takes a picture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) commencement ceremonies in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Ayah Bdeir, of Lebanon, takes a picture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) commencement ceremonies in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

These potential policy changes could come with unintended consequences. For example, they could inadvertently stifle potential innovation from visa applicants in nontechnical fields, or overly influence the degrees that international students choose to pursue.

That said, leaving the current system unchanged is much more counterintuitive to innovation in the U.S. semiconductor industry and risks harming the country’s national security interest.

Roadblocks to Reform

Support for admitting more high-skilled immigrants is broadly popular with voters, industry, and policy experts.

Yet reform has been elusive, even though the need within the semiconductor industry has climbed. What have been the roadblocks?

“The high-end visa puzzle has been, for some reason, tied to the broader immigration imbroglio that we have in our policy space,” says Shivakumar. “It’s become such a politicized issue that neither is being solved, despite the fact that we really do need to solve the high-end [immigration] issue.”

This means that the language politicians use against admitting lower-skilled workers, such as their perceived lower level of English, lower income, and net fiscal burden, inappropriately extends to restrict entry of high-skilled immigrants necessary to semiconductor innovation.

“We have to separate high-quality human talent, at MIT or Stanford or Purdue, from problems with economic and political refugees that our border has, [which] are quite different things,” Wessner suggests.

There have also been claims that foreign-born workers steal jobs from Americans. On June 22, 2020, the Trump administration issued a proclamation titled, “Proclamation on Suspension of Entry of Immigrants and Nonimmigrants Who Continue to Present a Risk to the United States Labor Market.”

“Under ordinary circumstances, properly administered temporary worker programs can provide benefits to the economy. But under the extraordinary circumstances of the economic contraction resulting from the COVID-19 outbreak, certain nonimmigrant visa programs authorizing such employment pose an unusual threat to the employment of American workers,” said the White House.

In addition, several high-profile national security incidents, such as a 2024 case involving a Chinese national stealing trade secrets from Google and a 2018 American University scandal involving a Russian graduate student, have inflamed rhetoric around IP theft by foreign-born workers and students. Utilizing workers from countries such as China and Russia, where U.S. geopolitical tensions are fraught, has become especially controversial.

Yet, by being overly restrictive of foreign-born workers, the United States risks missing out on essential talent critical to the semiconductor industry.

“We, above all, must not try to have a de facto suspicion of someone who comes from China simply because they come from China," said Wessner. "It makes no sense to bring them here, educate them, teach them everything we can, and then throw them out because we're suspicious."

These multifaceted concerns, paired with an overwhelming number of visa applications, complicate the already fraught climate surrounding high-skilled immigrants. Yet, integrating highly skilled workers is essential to maintaining the United States’ lead in the increasingly competitive semiconductor industry by filling critical talent gaps. Although the U.S. immigration system is under strain, and these policies will not fix the whole system, these changes can serve as an important and relatively popular first step.

Conclusion

The experiences of foreign workers struggling to obtain H-1B visas reflect on the broader problems of the nation’s broken immigration system, which inevitably harms the competitive and national security interests of the United States. Future immigration policy must reward the contributions necessary for the future of semiconductor and other advanced technology development.

As Shivakumar noted, “To be a leader in the semiconductor industry and even just stay in the competition, the U.S. needs to encompass a workforce that includes and sustains foreign workers.”

As President Trump adopts an “America First” policy, the avenue to achieving U.S. prosperity is supported by more flexible immigration policies capitalizing on highly skilled workers. Without strengthening provisions for foreign workers, the United States risks losing its status as a technological titan and will be vulnerable to challenge by foreign adversaries. Just as this industry relies on global supply chains and connectivity, harnessing international talent will be pivotal in ensuring the United States remains a driving leader in the semiconductor industry.

"The U.S. needs to encompass a workforce that includes and sustains foreign workers."

Dr. Sujai Shivakumar

Authors

Special Thanks:

Story: Gina Kim

Video: David Lotfi

Audio: Cera Baker

Data: William Taylor

Editorial: Mark Donaldson