Frozen Frontiers

China’s Great Power Ambitions

in the Polar Regions

China’s pursuit of great power status is drawing it to the frozen reaches of the world’s polar regions. In both the Arctic and Antarctic, China has undertaken ambitious expeditions and developed world-class research facilities. These investments have elevated China’s voice in polar affairs and afforded it an opportunity to shape the emerging geopolitical landscape.

Its growing physical footprint in the world’s most remote frontiers also serves to advance China’s broader strategic and military interests.

In the Arctic, melting ice sheets present a host of significant challenges for the global community. While leaders in Beijing are clear-eyed about the threats posed by climate change, Chinese strategists also see a potential silver lining.

The changing Arctic environment is expected to open new shipping routes that could reduce transit times for seaborne trade and make it easier for China to access the region’s natural resources.

Yet without sovereign jurisdiction in the Arctic, China leans on partnerships with other states to further its interests.

China has two permanent research stations in the region, one located in Norway’s Svalbard archipelago and the other in Iceland. Both sites support a diverse range of research, from marine ecology to atmospheric physics.

A third facility being utilized by China in northern Sweden is under scrutiny due to suspected ties to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), jeopardizing China's access to the site.

Beijing faces mounting roadblocks elsewhere. Several Arctic countries—including the United States—have voiced concerns about China’s presence in the region.

Left with few other options, China is stepping up its investments in Russia as it looks to Moscow as its strategic partner of choice in the Arctic.

This may prove to be China’s best path forward as both the climate and geopolitical competition heat up in the Arctic.

Arctic Aspirations

Despite being situated some 1,400 km (nearly 900 miles) south of the Arctic circle, China has styled itself a “near-Arctic state” and declared its ambitions to become a “polar great power” (极地强国) by 2030.

A 2018 Arctic policy white paper asserts that developments in the region have “a vital bearing” on China and lays out Beijing’s vision for utilizing the region’s natural resources and shaping Arctic governance.

Beijing has sought to access the region largely through scientific and commercial ventures, which officials claim give it the “right to speak” on Arctic affairs.

While China's Arctic research is primarily focused on advancing scientific knowledge—contributing to significant discoveries related to sea ice composition, space weather, and marine life—these accomplishments also serve Beijing's broader strategic objectives.

China’s Arctic research ecosystem fits within a larger bureaucracy that has historically supported Beijing's geopolitical ambitions.

Until recently, China's expansive polar research program was overseen by the State Oceanic Administration (SOA), which provided critical technical support for China's controversial construction and militarization of artificial islands in the South China Sea.

A 2018 government restructuring transferred most of the SOA's responsibilities to the powerful new Ministry of Natural Resources, keeping China's polar programs and South China Sea research activities under one roof.

China’s research expeditions in the Arctic often involve extensive oceanographic surveys and acoustic modeling, which mirror some of its activities in the South China Sea, where a thorough understanding of the region’s waters was also essential for the PLA Navy to operate effectively.

The connections between China's polar research programs and the PLA have raised alarms about the potential security risks in the Arctic. This is perhaps best on display in Sweden, where China began operating its first overseas satellite ground station in 2016, at the Esrange Space Center near Kiruna.

In 2020, the Swedish Space Corporation (SSC), which manages Esrange, opted not to renew its contracts with China over concerns that the station could be used for military intelligence gathering and surveillance. SSC’s decision extended beyond just Esrange to its other ground stations in South America and Australia. It remains unclear, however, when the contracts expire and if China’s access to SSC facilities has been severed.

The concerns surrounding China's activities at Esrange are indicative of the broader pushback that China faces. Over the past decade, several Chinese efforts have been blocked or rescinded by Arctic states for national security reasons.

The United States has voiced similar warnings. The 2019 Department of Defense report on China’s military power suggested that “civilian research could support a strengthened Chinese military presence in the Arctic Ocean.” The Biden administration’s October 2022 Arctic strategy likewise asserted that China has used its scientific engagements “to conduct dual-use research with intelligence or military applications.”

Military-civilian mixing is the main way for great powers to achieve a polar military presence.

~ China's 2020 Science of Military Strategy textbook

China’s own strategic writings make clear that the PLA has its sights on the region.

The 2020 edition of Science of Military Strategy—the most recent edition of an influential textbook on military thinking published by China’s National Defense University—states bluntly that “military-civilian mixing is the main way for great powers to achieve a polar military presence.” It adds that China should “give full play to the role of military forces in supporting polar scientific research and other operations.”

The dual-use nature of Arctic research epitomizes China’s military-civil fusion (MCF) strategy, which aims to marshal civilian resources to support the PLA, and ultimately to fuse together China’s various national strategies to simultaneously advance security and development goals. President Xi Jinping has significantly elevated the importance of MCF, and it is unsurprising that this thinking is being applied to the Arctic.

Courting the Bear

Concerns about the potential military applications of Chinese scientific research are not new, but recent events have brought them into sharper focus. The conflict in Ukraine has deepened political fault lines, leaving many European governments viewing Beijing and Moscow as increasingly aligned against democratic states. Finland’s recent accession to NATO and Sweden’s push for membership have further strained their relationship with China.

In this emerging geopolitical landscape, China’s prospects of expanding its presence in the Arctic via Nordic states look increasingly dim and its partnership with Russia appears to be taking center stage.

China has long viewed Russia as a gateway to the Arctic. The two countries began holding official dialogues on the Arctic more than a decade ago, but Russia has historically bristled at China’s push into its far north. Russia initially opposed China’s campaign to become an observer state of the Arctic Council, and in 2012, it blocked Chinese research vessels from conducting surveys along the Northern Sea Route.

Part of Moscow’s concern likely stems from the fact that the Russian military operates some of its most sensitive strategic assets there, including ballistic missile submarines, strategic test sites, missile defense systems, and advanced radar arrays.

This dynamic may now be changing. The war in Ukraine has left Russia increasingly isolated and reliant on China for crucial investments in technology and infrastructure.

The conflict has also left the Arctic Council in flux, as Russia has been shunned by the remaining member states, and China has said it will refuse to recognize the body without Russia’s participation.

Chinese scholars have previously analyzed how best to gain a foothold in the Russian Arctic. In 2019, prominent academics from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Fuzhou University conducted a study to identify which Russian ports along the strategic Northern Sea Route hold the greatest potential for facilitating Chinese access to the region.

The report ranked 13 Russian ports based on five primary factors: natural conditions, infrastructure, port operation, interior environment, and geographic location. It also assessed 17 secondary factors, including “strategic value.”

Major Chinese firms have already homed in on several of the key ports identified in the study. Over the last seven years, a subsidiary of the state-owned defense industry giant China Poly Group has poured $300 million into a coal terminal in Murmansk and agreed to develop a deepwater port at Arkhangelsk.

Chinese financers also provided up to 60 percent of the capital for Russia’s Yamal liquefied natural gas project terminating in the port city of Sabetta. The project is considered the “crown jewel” of Russia's investments in the Northern Sea Route and there are hopes it could produce up to 926 billion cubic meters of liquefied natural gas from the South Tambey field.

Yamal Natural Gas Plant

Yamal Natural Gas Plant

China is looking to expand its presence in Russia’s mineral sector as well. In January 2023, the China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) signed a deal with Russia's Rustitan to help develop the Pizhemskoye titanium and quartz deposits in the Komi Republic near the Arctic Circle.

The sprawling CCCC gained international notoriety for being one of the 24 entities that the Trump administration sanctioned for supporting China’s construction of artificial islands in the South China Sea.

The project is a key pillar of the Kremlin’s long-term strategy to transform the Northern Sea Route into a major throughway of global trade and includes the development of a deepwater port at Indiga and the construction of a five- to six-billion dollar Sosnogorsk–Indiga railway connection.

Russian president Vladimir Putin has cleared the political runway for China’s deepening involvement. In a high-profile March 2023 meeting in Moscow, Putin told Xi, “We see cooperation with Chinese partners in developing the transit potential of the Northern Sea Route as promising.” If successful, these projects could further embed China’s state-owned champions deep into the Russian Arctic.

China is looking to expand its presence in Russia’s mineral sector as well. In January 2023, the China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) signed a deal with Russia's Rustitan to help develop the Pizhemskoye titanium and quartz deposits in the Komi Republic near the Arctic Circle.

The sprawling CCCC gained international notoriety for being one of the 24 entities that the Trump administration sanctioned for supporting China’s construction of artificial islands in the South China Sea.

The project is a key pillar of the Kremlin’s long-term strategy to transform the Northern Sea Route into a major throughway of global trade and includes the development of a deepwater port at Indiga and the construction of a five- to six-billion dollar Sosnogorsk–Indiga railway connection.

Russian president Vladimir Putin has cleared the political runway for China’s deepening involvement. In a high-profile March 2023 meeting in Moscow, Putin told Xi, “We see cooperation with Chinese partners in developing the transit potential of the Northern Sea Route as promising.” If successful, these projects could further embed China’s state-owned champions deep into the Russian Arctic.

Antarctic Expansion

Whereas geopolitical headwinds have chilled China’s options in the Arctic, Beijing has a freer hand in Antarctica. China is currently undertaking the most significant expansion of its footprint there in a decade.

The 1959 Antarctic Treaty outlaws the use of Antarctica for military purposes but encourages scientific research. Most Antarctic research supports legitimate scientific objectives. Yet just as in the Arctic, it can also be leveraged for dual-use purposes.

The 2022 Department of Defense report on China’s military notes that “[China’s] strategy for Antarctica includes the use of dual-use technologies, facilities, and scientific research, which are likely intended, at least in part, to improve PLA capabilities.” It adds that China’s facilities there can serve as reference stations for China’s dual-use BeiDou satellite navigation network, Beijing’s alternative to the U.S.-run global positioning system.

[China’s] strategy for Antarctica includes the use of dual-use technologies, facilities, and scientific research, which are likely intended, at least in part, to improve PLA capabilities.

~U.S. Department of Defense 2022 China military power report

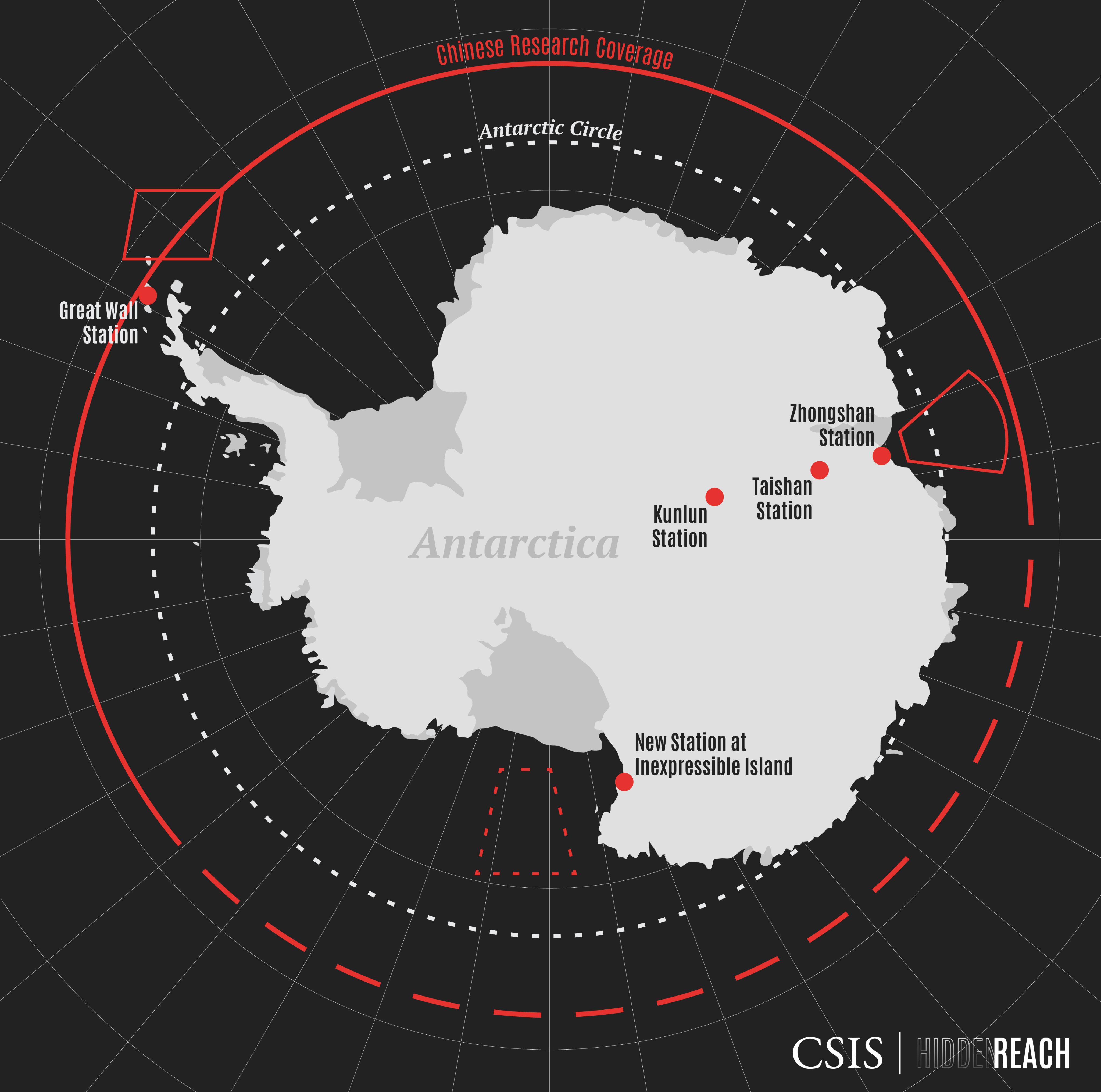

Like other scientific powers, China has peppered the continent with research stations. China currently operates two permanent stations on Antarctica’s coasts, which are readily accessible by China’s fleet of two Xuelong (Snow Dragon) icebreakers. An additional station and base camp have also been set up on the remote Antarctic Plateau—the coldest area on the planet.

Adapted from a 2021 Chinese environmental evaluation report submitted to the Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty.

Adapted from a 2021 Chinese environmental evaluation report submitted to the Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty.

Work is currently underway to construct a fifth facility. Situated on Inexpressible Island near the Ross Sea, the new station’s position is triangulated with China’s other coastal stations to fill in a major gap in China’s coverage of the continent’s expansive coastline and beyond.

New satellite imagery shows that Chinese builders have begun making significant progress on the site for the first time since construction began in 2018. After several years of dormancy, new support facilities and groundwork for a larger structure have appeared at the site. The station will likely continue to progress in fits and starts, with expeditions to construct the station limited to the milder Antarctic summers.

Once completed, the 5,000 square meter station is expected to include a scientific research and observation area, an energy facility, a main building, a logistics facility, and a wharf built for China’s Xuelong icebreakers.

In February 2020, a team of U.S. officials from the State Department and other agencies inspected the new site and found no specific military equipment or personnel at the nascent facility. However, once completed, the facility will include a satellite ground station, which, like China’s other ground stations, will have inherent dual-use capabilities.

While essential for tracking and communicating with China’s growing array of scientific satellites, ground stations can support intelligence collection.

Importantly, the station’s position may enable it to collect signals intelligence from U.S.-allied Australia and New Zealand and could collect telemetry data on rockets launching from newly established space facilities in both countries.

The new station joins a lineup that began in 1985 with China’s first Antarctic research facility, the Great Wall Station. Situated on a string of islands that jut out far into the South Atlantic Ocean, the Great Wall Station offers a prime vantage point along the Drake Passage, a key sea line of communication linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Replete with antennas and other monitoring equipment, the station has the capability to keep a watchful eye on commercial and naval vessels transiting the strategic passage.

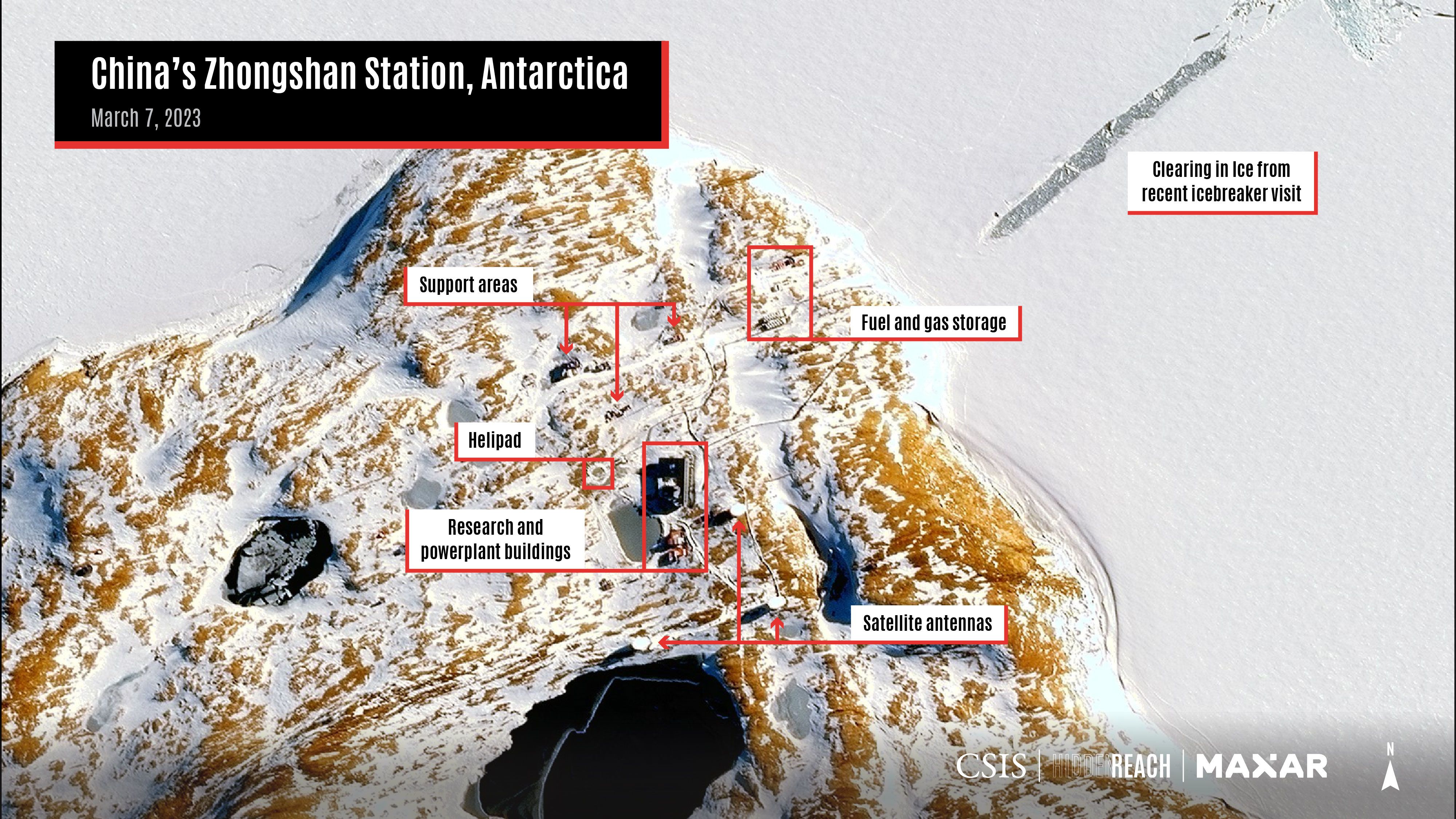

Further east, recent reports suggest China plans to expand its Zhongshan Station with additional antennas. The antennas will reportedly be built by China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC), a major player in China’s space sector that the U.S. Defense Department and Treasury Department have designated a military entity.

Recent satellite imagery indicates that no new antennas have been built, but once installed they will supplement the station’s existing antennas in sending and receiving data from Chinese satellites in polar or near-polar orbits, including those in China’s dual-use BeiDou navigation system.

The Zhongshan Station’s assets could be leveraged to collect intelligence on foreign militaries in the Indian Ocean, including on the joint U.S.-UK Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia. It could also play a support role in monitoring India’s developing naval forces operating in the region.

China's growing scientific presence in Antarctica aligns with its broader political objectives. In the past, China faced difficulties obtaining consultative party status to the Antarctic Treaty, due both to its lack of scientific activity on the continent and the political concerns of Western powers.

Its growing contributions to Antarctic science may pave the way for China to have a greater say in the future governance of the region. For instance, in 2048, the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty could potentially be renegotiated, giving China an opportunity to shape future rules around mineral resource extraction.

China’s expanding presence in both the Arctic and Antarctic is part of its broader pursuit of global great power status. Its contributions to polar science have given it a voice and a presence in polar affairs, while opening the door to advance military and strategic goals. China is by no means the only great power to use science for strategic ends, yet mounting geopolitical competition is raising the stakes for China's polar pursuits.

International cooperation will be necessary for the responsible management and stewardship of the poles, and China can play a positive role in those efforts. Still, the United States and its allies should carefully monitor China’s evolving activities and push for greater transparency.

Washington should also focus on crafting stronger diplomatic and economic partnerships with like-minded countries and strengthening international governance mechanisms. Through these efforts, the United States can help ensure the world's frozen frontiers do not become the next hot spots of geopolitical competition.

This report was produced by the Andreas C. Dracopoulos iDeas Lab.

Written by Matthew P. Funaiole, Brian Hart, Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., and Aidan Powers-Riggs.

Research support by Jaehyun Han.

Special thanks to Bonny Lin, Jennifer Jun, Sarah Grace, Trym Eiterjord, and Henry Li.

Production by Michael Kohler.

Design support by William Taylor.

Development support by Mariel de la Garza.

Copyediting support by Katherine Stark.

Satellite Imagery: Copyright © 2023 by Maxar Technologies

Photo & Video: Xinhua News Agency via Getty Images, Vanderlei Almeida/AFP via Getty Images, мрем via Wikimedia, Envato Elements