Surveying the Seas

China’s Dual-Use Research Operations

in the Indian Ocean

China is undertaking sweeping efforts to transform its navy into a formidable “blue water” force capable of projecting power far beyond its shores. As the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) ventures into less familiar waters like the Indian Ocean, Beijing has sought to deepen its understanding of the maritime operating environment by studying water conditions, currents, and the seafloor.

To survey the Earth’s oceans, China has developed the world's largest fleet of civilian research vessels. While these ships support scientific and commercial objectives, they are also being used to advance Beijing’s strategic ambitions.

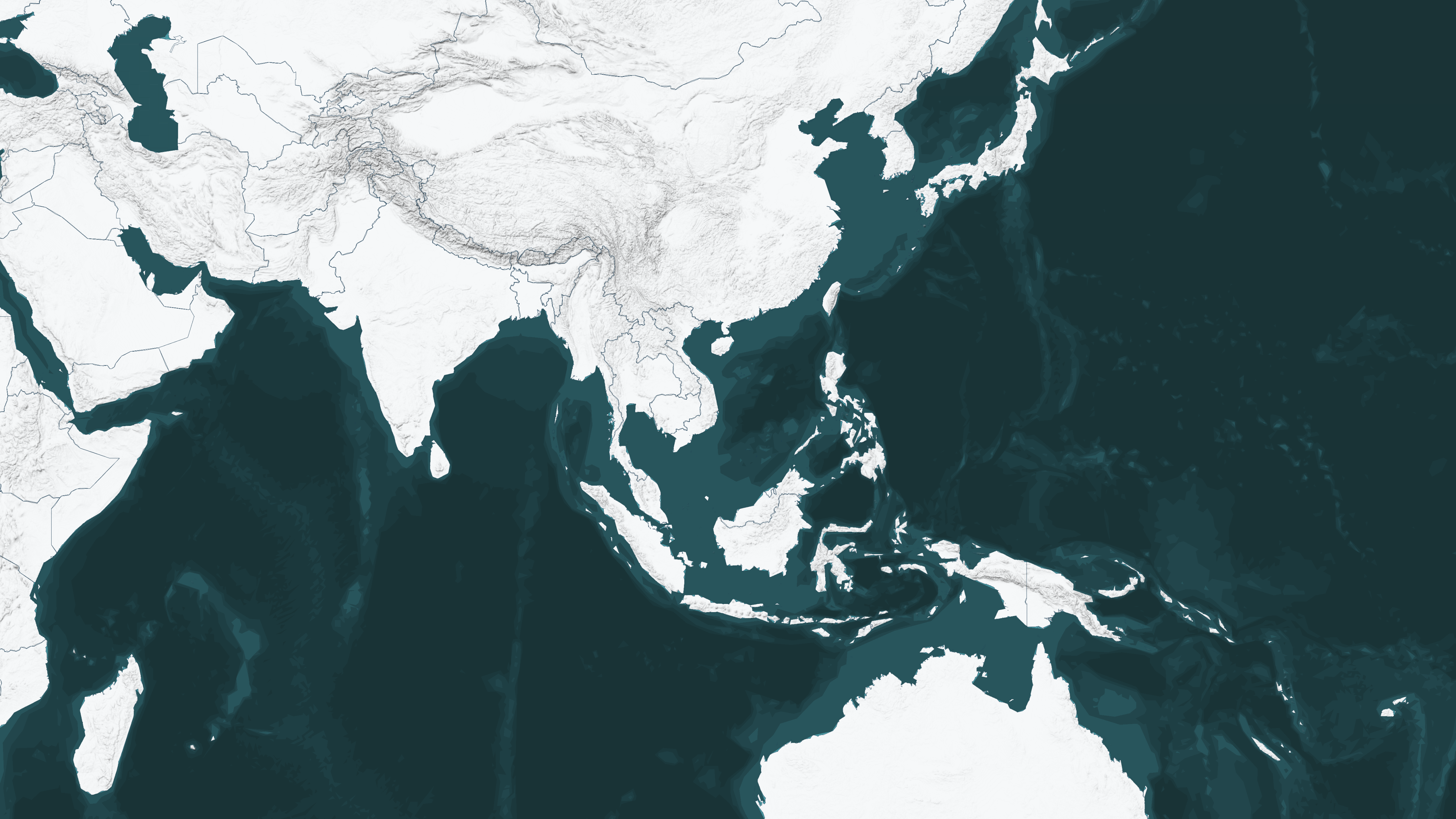

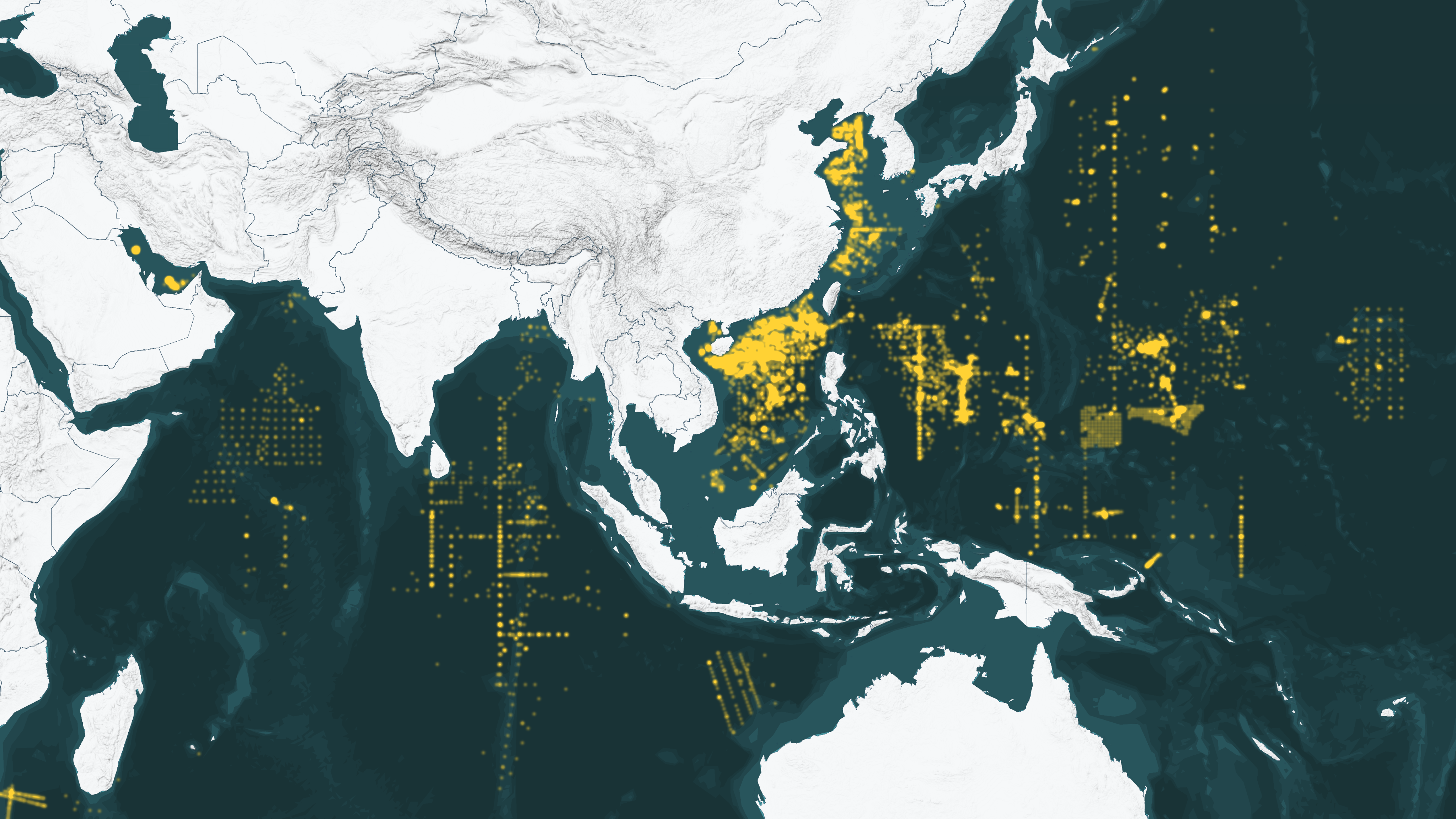

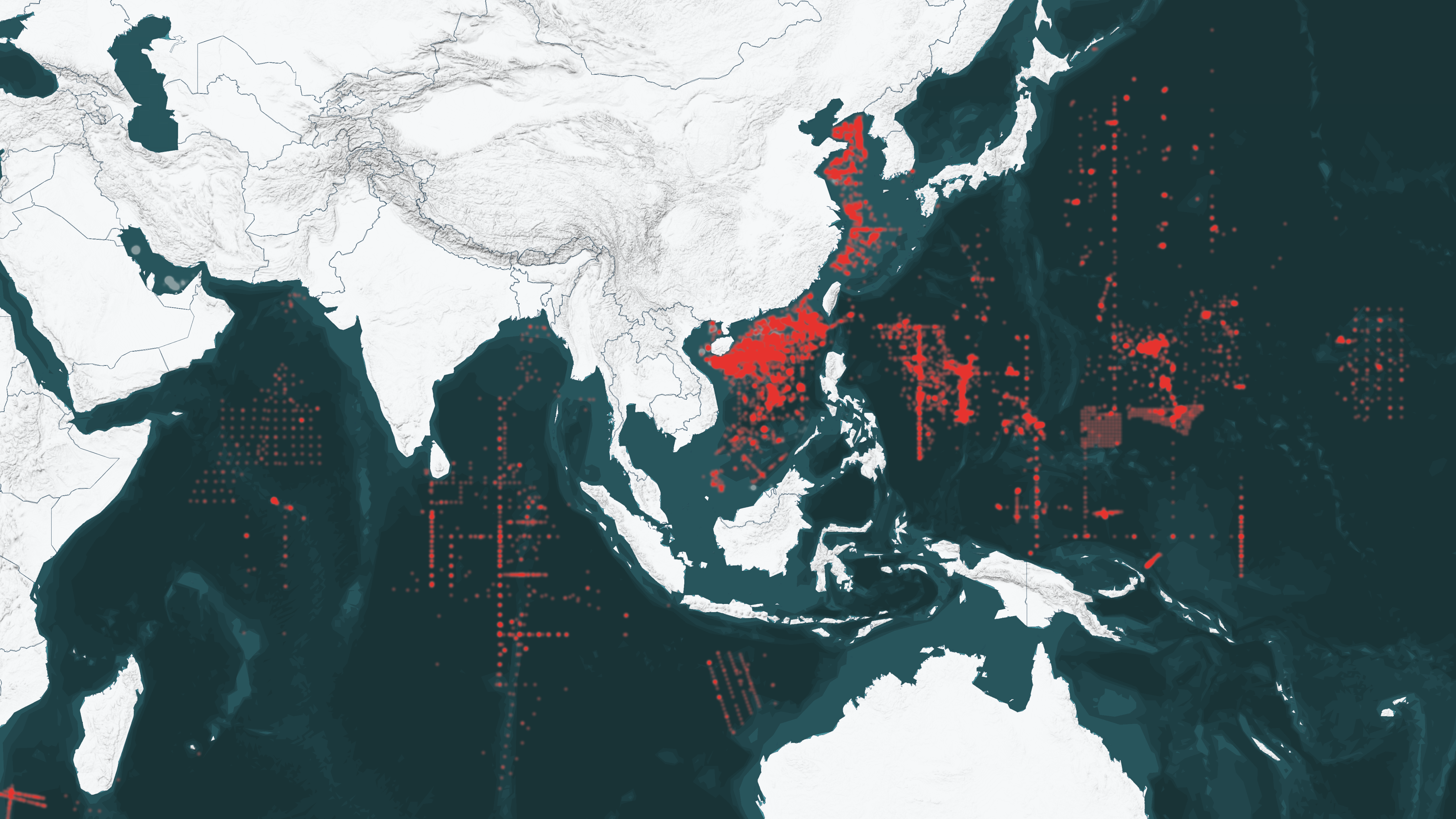

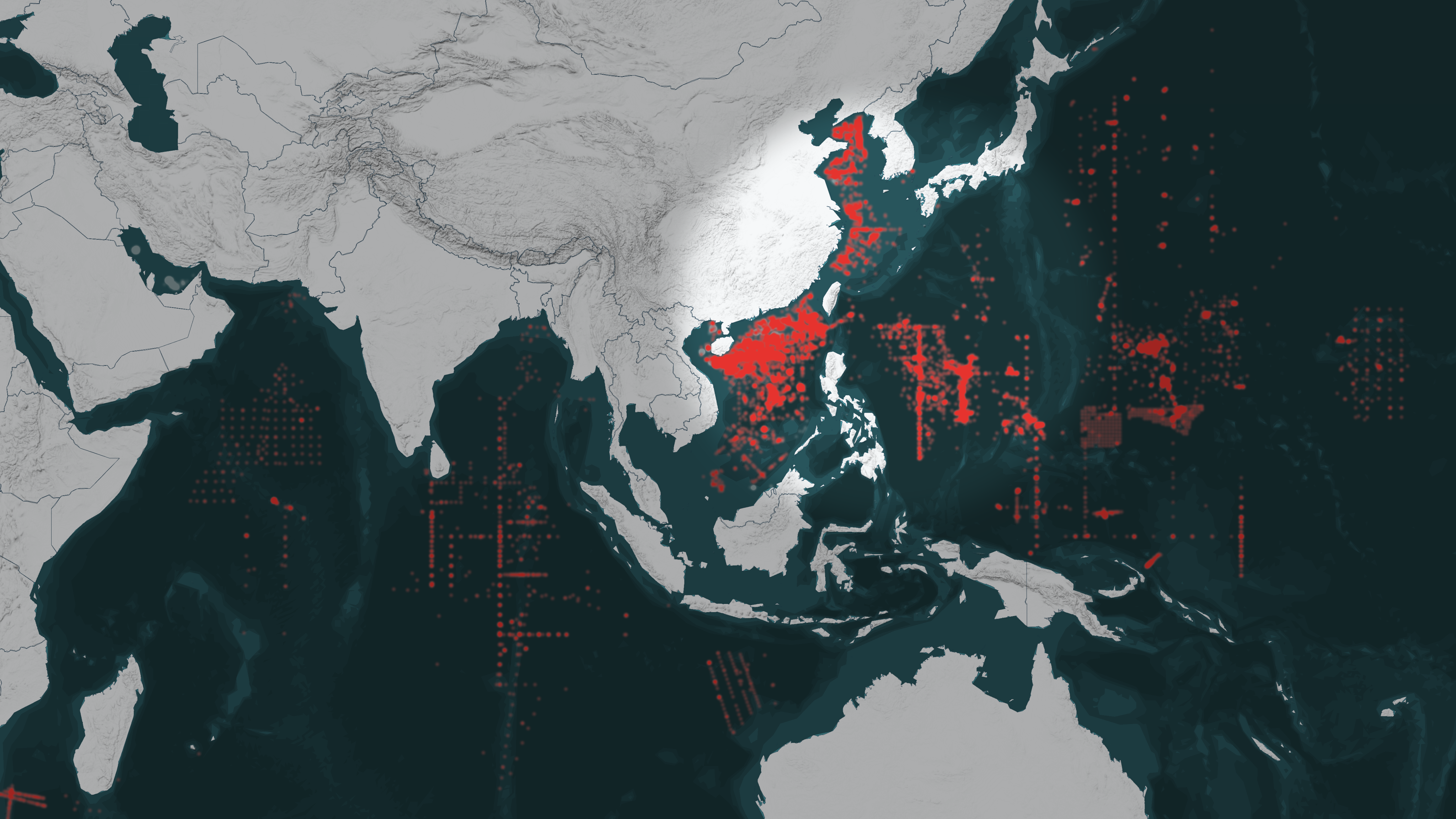

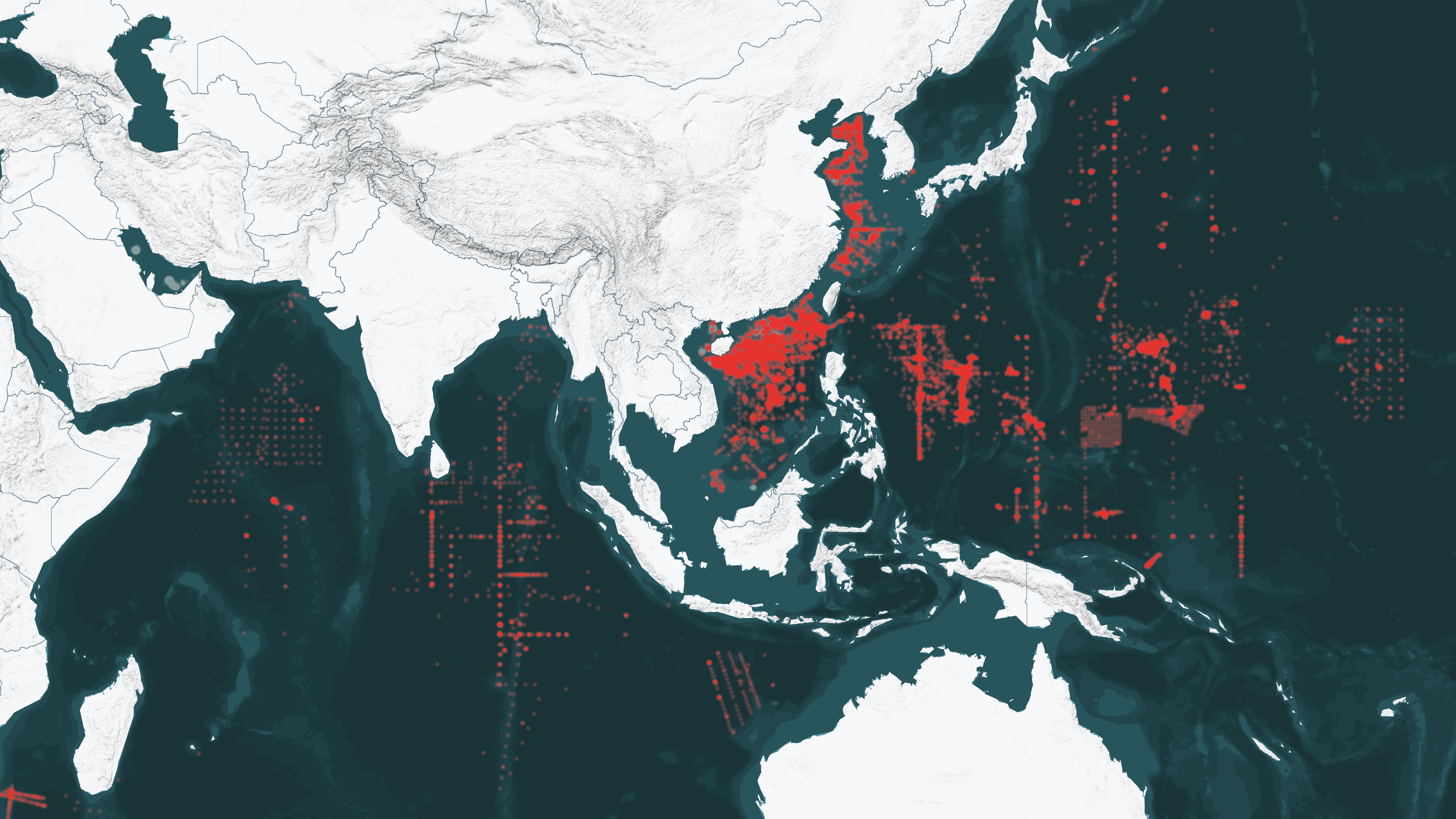

Chinese oceanographic surveys span the globe.

Maritime activity data collected using the Windward Intelligence Platform reveals Chinese survey vessels have carried out hundreds of thousands of hours of operations globally over the past four years.

Hidden Reach analyzed Chinese oceanographic missions since 2020 and identified 64 active research and survey vessels.

China’s dual-use approach to oceanographic research raises questions about the nature of these activities. Many vessels that undertake missions for peaceful purposes are also capable of providing the PLA with critical data about the world’s oceans.

Of the 64 active vessels, over 80 percent have demonstrated suspect behavior or possess organizational links suggesting their involvement in advancing Beijing’s geopolitical agenda.

China’s surveying operations have been heavily concentrated along its maritime periphery in the South China Sea and western Pacific Ocean.

But it has also set its sights on the Indian Ocean, an emerging arena of competition between Beijing and New Delhi.

The PLA can leverage the insights gained from these missions to enhance its knowledge of the dynamic undersea environment—a crucial precursor to confidently deploying naval forces abroad.

Exploring and mapping the world’s oceans is not unique to China. Dozens of countries have active oceanographic research programs, which contribute to global efforts to study climate change, marine life, geology, and the distribution of natural resources.

China is also not alone in applying oceanographic research to support military needs. Yet the scale of China’s activities is immense, and the line between its civilian and military research is heavily blurred.

Beijing’s lack of transparency makes it challenging to discern the true nature of its survey operations, but three specific indicators shed light on which vessels may be supporting Beijing’s military and national security objectives.

Vessel Ownership and Type

Many of China’s research vessels are owned and operated by state-affiliated organizations with close ties to the Chinese military. For example, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Chinese Academy of Sciences both operate research vessels and have signed cooperation agreements with the PLA.

Some survey ships were in service with the PLA before entering civilian service. Hulls in the Xiang Yang Hong (向阳红) class, for example, were originally built for the Chinese navy but were later transferred to civilian authorities with ties to the PLA.

Other ships are operated directly by the Chinese Coast Guard, which ultimately reports to the country’s Central Military Commission.

Chinese officials are not always quiet about the dual function of these ships. During the commissioning of the Shiyan 06 (实验-06), officials acknowledged the ship would “provide strong scientific and technological support for homeland security.”

Military-Affiliated Port Visits

Many Chinese survey ships have a record of calling at port in military-affiliated facilities in China. This includes Sanya, Guangzhou, Qingdao, and other ports known to host major contingents of PLA Navy warships and maritime militia vessels. Some have also visited China’s unlawfully constructed military outposts in the South China Sea.

Notably, some vessels have gone dark for hours or days while near PLA installations, a potential sign of intentional efforts to obscure activities there.

Activities

Behavior at sea can also raise red flags. Repeated instances of “spoofing” (providing falsified identification information) or “going dark” (turning off automatic identification system signals for extended periods) are important warning signs. Data from Windward indicates these activities occur frequently—sometimes near foreign military facilities.

In other instances, China has deployed research vessels to strengthen its presence in geopolitical hotspots. Commercial and scientific research ships, such as those operated by the state-owned China Oilfield Services Limited (COSL), have played a major role in helping Beijing assert its claims of “indisputable sovereignty” over vast swaths of the contested South China Sea.

Some ships have conducted survey operations within the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of other countries without prior approval, which is prohibited under international law. These activities have sparked diplomatic spats, including a 2019 confrontation between an Indian warship and Chinese research vessel operating unauthorized in India’s EEZ.

Exploring and mapping the world’s oceans is not unique to China. Dozens of countries have active oceanographic research programs, which contribute to global efforts to study climate change, marine life, geology, and the distribution of natural resources.

China is also not alone in applying oceanographic research to support military needs. Yet the scale of China’s activities is immense, and the line between its civilian and military research is heavily blurred.

Beijing’s lack of transparency makes it challenging to discern the true nature of its survey operations, but three specific indicators shed light on which vessels may be supporting Beijing’s military and national security objectives.

Vessel Ownership and Type

Many of China’s research vessels are owned and operated by state-affiliated organizations with close ties to the Chinese military. For example, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Chinese Academy of Sciences both operate research vessels and have signed cooperation agreements with the PLA.

Some survey ships were in service with the PLA before entering civilian service. Hulls in the Xiang Yang Hong (向阳红) class, for example, were originally built for the Chinese navy but were later transferred to civilian authorities with ties to the PLA.

Other ships are operated directly by the Chinese Coast Guard, which ultimately reports to the country’s Central Military Commission.

Chinese officials are not always quiet about the dual function of these ships. During the commissioning of the Shiyan 06 (实验-06), officials acknowledged the ship would “provide strong scientific and technological support for homeland security.”

Military-Affiliated Port Visits

Many Chinese survey ships have a record of calling at port in military-affiliated facilities in China. This includes Sanya, Guangzhou, Qingdao, and other ports known to host major contingents of PLA Navy warships and maritime militia vessels. Some have also visited China’s unlawfully constructed military outposts in the South China Sea.

Notably, some vessels have gone dark for hours or days while near PLA installations, a potential sign of intentional efforts to obscure activities there.

Activities

Behavior at sea can also raise red flags. Repeated instances of “spoofing” (providing falsified identification information) or “going dark” (turning off automatic identification system signals for extended periods) are important warning signs. Data from Windward indicates these activities occur frequently—sometimes near foreign military facilities.

In other instances, China has deployed research vessels to strengthen its presence in geopolitical hotspots. Commercial and scientific research ships, such as those operated by the state-owned China Oilfield Services Limited (COSL), have played a major role in helping Beijing assert its claims of “indisputable sovereignty” over vast swaths of the contested South China Sea.

Some ships have conducted survey operations within the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of other countries without prior approval, which is prohibited under international law. These activities have sparked diplomatic spats, including a 2019 confrontation between an Indian warship and Chinese research vessel operating unauthorized in India’s EEZ.

The blurred boundaries between China’s oceanographic research ecosystem and its expansive national security apparatus bear the hallmarks of Beijing’s military-civil fusion (军民融合) strategy, which seeks to break down barriers between the country’s civilian and military scientific, technological, and economic development.

China’s national economic blueprint, the 14th Five Year Plan, names deep sea exploration as one of its seven focus areas for scientific and technological research and calls for the development of “submarine scientific observation networks.” In 2021, the Ministry of Natural Resources laid out specific guidance on furthering the Five Year Plan, including linking ocean surveying to military objectives.

PLA personnel have written extensively on the need for a robust set of advanced deep-sea technologies to support undersea warfare, a domain where China considerably lags the U.S. military. The data collected by China’s civilian research fleet, which is outfitted with cutting-edge measuring and monitoring equipment, can help fill in major gaps in the PLA Navy’s undersea capabilities.

The connections between the Chinese military and civilian oceanographic research are often in plain sight. The PLA Navy Submarine Academy openly touts its frequent collaborations with China’s major maritime research institutions.

The Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (QNLM) is the crown jewel in China’s oceanographic research technology ecosystem. It is located among a cluster of advanced research labs built near the submarine academy’s main campus.

These partnerships have raised security concerns abroad. Texas A&M University terminated a research partnership with QNLM in 2022, citing “more than 200 instances of Foreign Talent Recruitment activity.” In the same year, the U.S. Department of Commerce added QNLM to its Entity List due to its involvement in supporting China’s military modernization efforts.

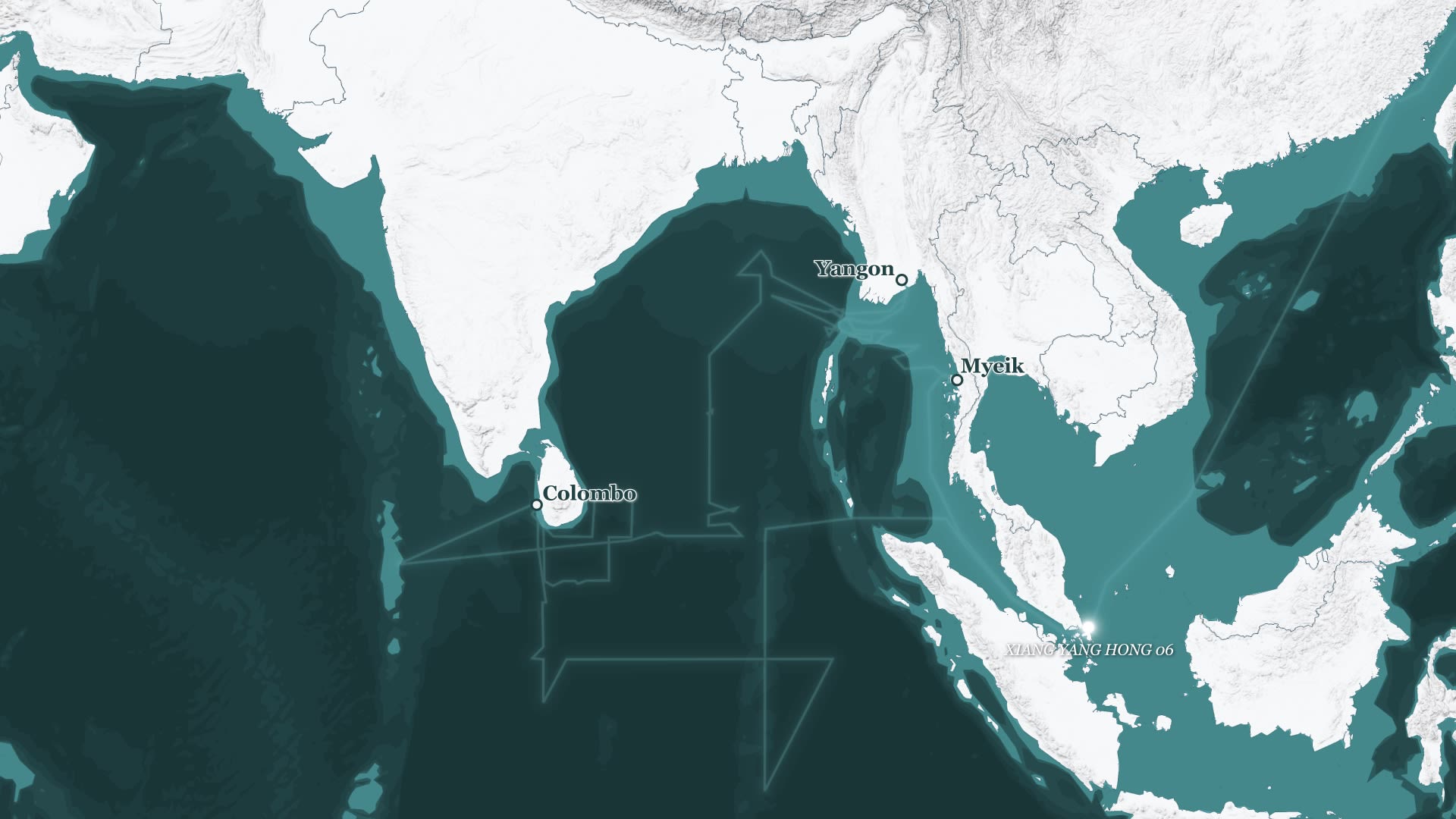

XIANG YANG HONG 06

向阳红 06

One of China’s most extensive expeditions took place in 2019 and 2020, when the research vessel Xiang Yang Hong 06 traveled more than 10,000 kilometers over 110 days to survey vast swaths of the Indian Ocean. Scientists from Sri Lanka and Myanmar joined for parts of the ship’s expedition.

Part of its mission involved releasing 12 advanced underwater gliders and deploying 15 profiling floats, which spent months collecting data on the area’s hydrological conditions. That data was then fed back to China via satellite transmission.

These floats are part of an effort to build up a real-time ocean observation network of hundreds of devices spanning the “Two Oceans and One Sea” (两洋一海) region, a conceptualization of the Pacific and Indian Oceans and South China Sea put forward by Beijing as a focus area for maritime surveillance.

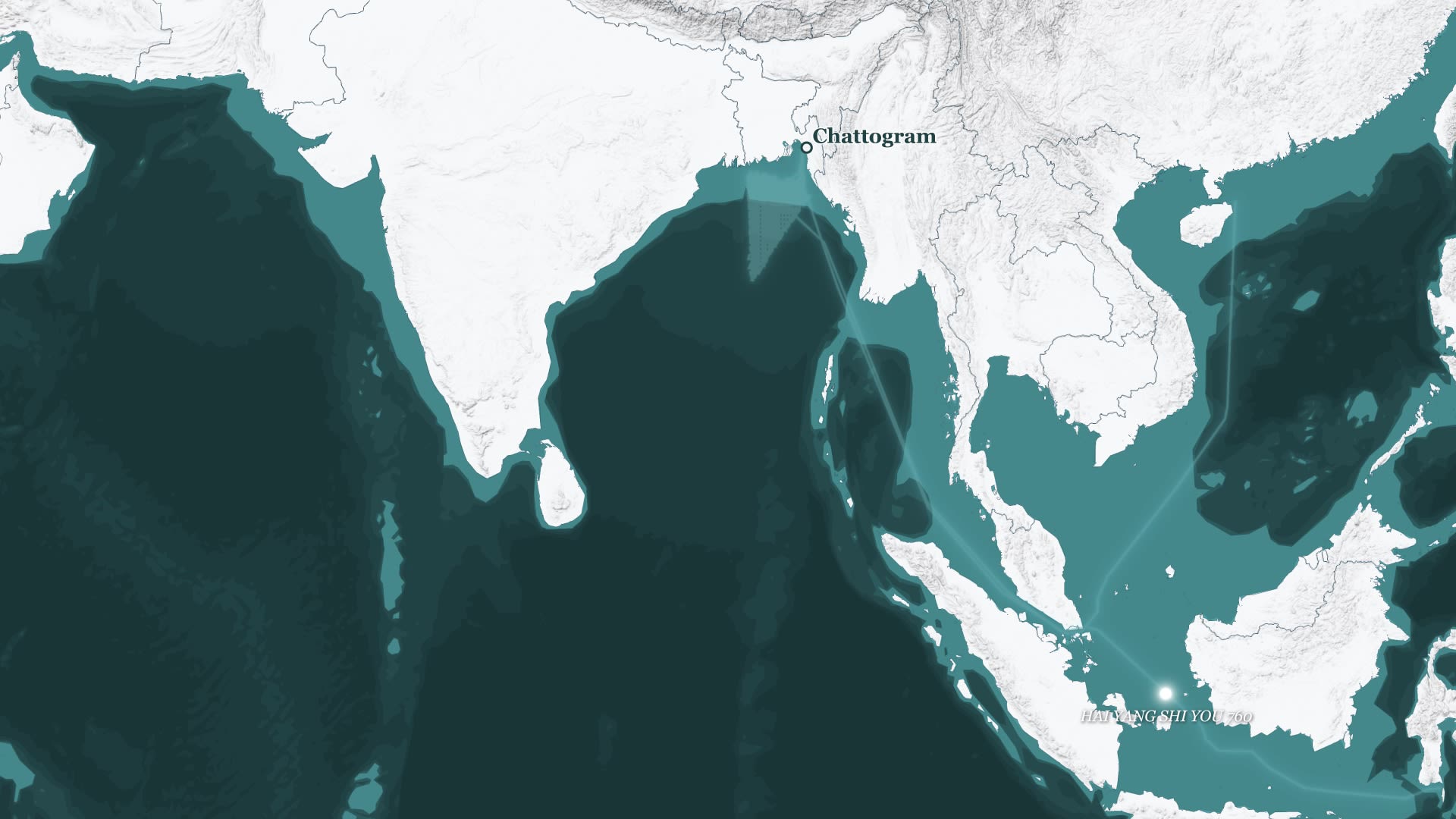

HAI YANG SHI YOU 760

海洋石油 760

In another telling example, the seismic survey ship Hai Yang Shi You 760 completed a four-month ocean bed mapping mission in early 2023.

The vessel is owned and operated by COSL, a subsidiary of the state-owned oil giant China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC). During its mission, it followed an extensive “lawnmower” path within Bangladesh’s EEZ, indicating the vessel was exploring the seabed for oil and gas deposits.

CNOOC ships and large-scale rigs have been routinely deployed to assert Beijing’s sovereignty claims in the highly contested South China Sea. In 2012, CNOOC’s chairman famously referred to the firm’s oil rigs as a “strategic weapon” supporting national interests. CNOOC’s ties to the PLA led the U.S. Treasury Department to add the firm to its Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies List.

There is no indication that the Hai Yang Shi You 760 operated within Bangladesh’s EEZ without official consent. Its repeated port calls at Chittagong suggest it received permission. Nonetheless, the seismic and bathymetric data collected during the survey could be of significant value to the PLA.

Once the survey was complete, the Hai Yang Shi You 760 returned to its home port at Zhanjiang, just beside the headquarters of the PLA Navy’s South Sea Fleet.

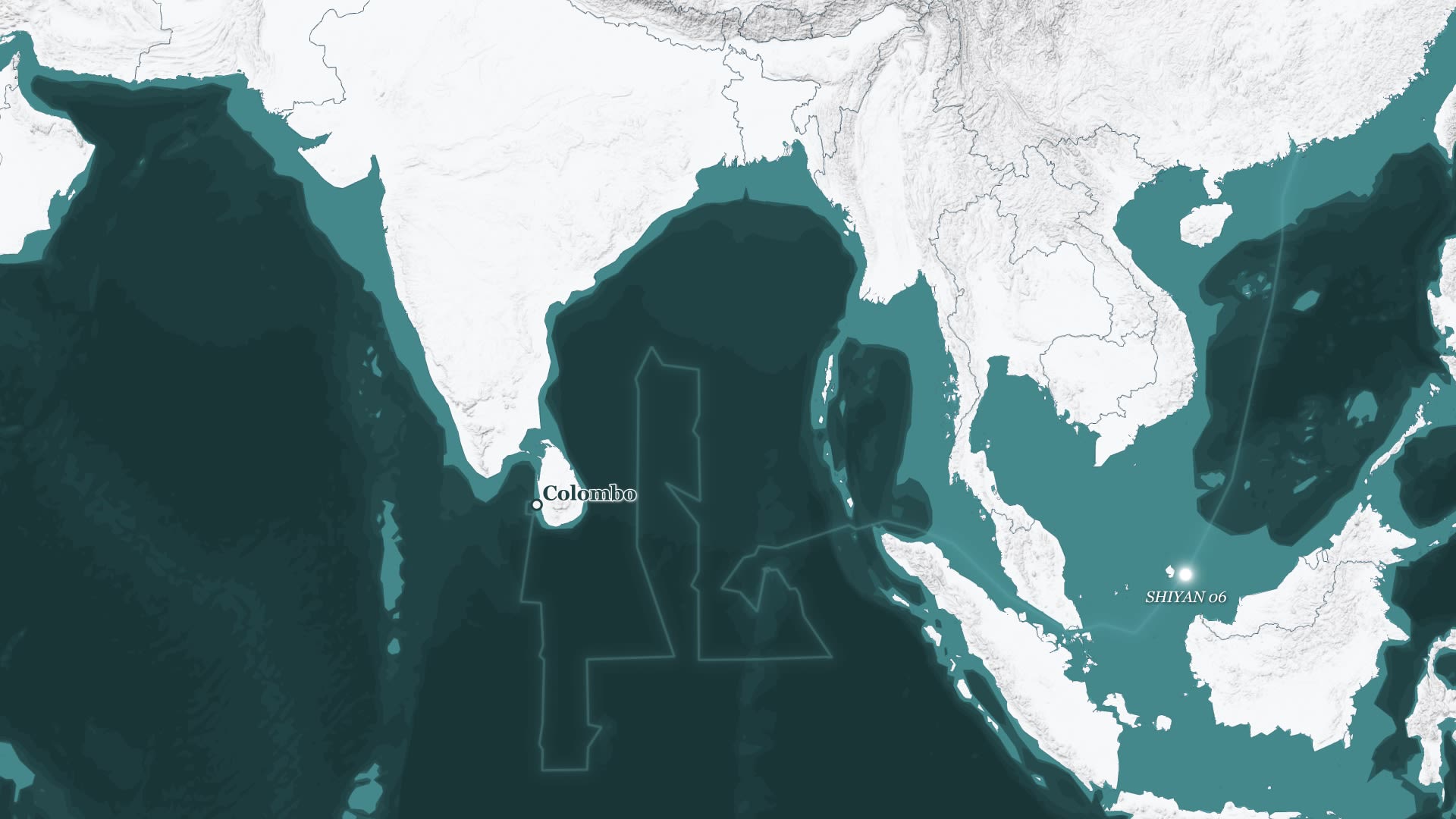

SHIYAN 06

实验 06

More recently, in October 2023, the research vessel Shiyan 06 entered the eastern Indian Ocean bound for the Port of Colombo in Sri Lanka.

The vessel is operated by the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, a research institute that has provided technical and logistical support for China’s militarization of the South China Sea.

Sri Lanka initially demurred on China’s requests to dock the vessel at Colombo due to objections raised by India. Local researchers also expressed concern about their lack of access to the data gathered by Chinese expeditions. Colombo eventually relented, however, allowing the Shiyan 06 to dock for five days before it left to execute research surveys along the island’s west coast.

Beijing’s interest in Sri Lanka goes well beyond scientific pursuits. China’s massive investments in ports and other infrastructure there have raised concerns—including from the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD)—that the PLA has likely considered setting up a military facility in the island nation.

While Chinese surveys in the Indian Ocean contribute to scientific and commercial efforts, the data collected on research missions has clear military value—especially to submarine operations.

The most recent Chinese defense white paper highlights the need for the PLA to support “far seas protection and strategic projection.” The Indian Ocean is a pivotal region for the PLA as it pushes to extend its “strategic perimeter” (战略外线) farther from China’s borders.

The underwater domain is critical to China’s interests in the Indian Ocean. Chinese submarines could be called on to support a wide range of missions, ranging from intelligence collection to nuclear deterrence patrols. In a crisis, Chinese attack submarines operating there could complicate attempts by U.S. or allied forces to interdict China’s supply lines or traverse the region to reach the Pacific.

Expanding submarine operations, however, requires overcoming significant hurdles. China’s lack of a nearby military facility forces its submarines to navigate key chokepoints between the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean.

Beijing may seek to address this vulnerability. The U.S. DOD assesses that China has likely considered 18 countries as potential hosts for an additional overseas military facility. Of these, 11 ring the massive Indian Ocean.

Even with a regional military facility, submarine operations remain highly complex—a fact that has been brought home to the PLA Navy through its own experiences and those of foreign navies. In 2014, a Chinese submarine operating near Hainan Island was nearly lost when it encountered an unexpected change in water density, causing the submarine to sink rapidly into an underwater trench. The PLA Navy awarded the captain and crew high honors for successfully averting disaster.

Safely navigating submarines requires thorough knowledge of complex undersea conditions. Changes in subsurface topography, currents, thermoclines, salinity, and other factors have major impacts on how submarines navigate their surroundings.

Civilian oceanographic research helps to arm the PLA Navy with critical data, enhancing its capability to safely deploy in distant waters.

The PLA and its civilian surrogates are harvesting data from the world’s oceans. While scientific and commercial benefits may accrue from Chinese oceanographic research, these activities may also prove crucial for the PLA in expanding its operational reach and capabilities in the Indian Ocean.

This expansion poses a significant challenge to key regional players like India, as well as to the United States and its allies. Beijing’s track record of defying international norms to serve its own interests further heightens the stakes.

Some of China’s erstwhile partners in the region have started to pull back from research collaboration with China. At India’s encouragement, Sri Lanka announced in January 2024 that it would implement a one-year pause on Chinese research vessels docking at its ports. The country’s foreign minister suggested the ban would allow Sri Lanka to develop its capacity to “participate in such research activities as equal partners.”

Such efforts are critical to holding Beijing to account. Engagement with Chinese researchers should not be unnecessarily curtailed, but these collaborations should be handled equitably and transparently.

In the long term, countries can also work together to ensure that a heightened PLA presence in the Indian Ocean does not destabilize the region.

India’s cooperation is crucial, and New Delhi has already demonstrated a degree of willingness to engage with partners. Amid simmering tensions with China, India has supported maritime security efforts with members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (or Quad).

As China charts its course in the Indian Ocean, Washington and its partners should keep a close watch on Chinese actors and explore opportunities to cooperate as an effective ballast.

Written by Matthew P. Funaiole, Brian Hart, and Aidan Powers-Riggs.

Research support by Jaehyun Han.

Special thanks to Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., Gregory Poling, Harrison Pretat, J. Michael Dahm, and Anu Anwar.

Production, design, and maps by Michael Kohler.

Development support by Lindsay Allison, Mariel de la Garza, and José Romero.

Copyediting support by Katherine Stark.

Getty Images: CCTV+, Ishara S. Kodikara/AFP, Johanes Christo/NurPhoto, Sonny Tumbelaka/AFP, Guo Cheng/Xinhua, Mark Schiefelbein/AFP, Ted Aljibe/AFP

Map & Data: © Mapbox, © OpenStreetMap