DEEP BLUE SCARS

Environmental Threats

to the South China Sea

By Monica Sato, Harrison Prétat, Tabitha Mallory, Hao Chen, and Gregory Poling | December 18th, 2023

A hidden crisis is unfolding across the South China Sea. While regional powers work to strengthen their claims to disputed waters and territories there, the marine environment in which they maneuver has been declining to critical levels.

Human activity is causing severe ecological damage in the South China Sea.

In recent decades, increased fishing, dredging, and land fill, along with giant clam harvesting, have taken a devastating toll on thousands of species found nowhere else on earth.

To ensure the security and longevity of the plants, animals, and people that call the South China Sea home, this critical environment must be understood through an ecological, rather than merely geopolitical, lens.

I. Understanding Life in the South China Sea

The South China Sea has one of the highest levels of marine biodiversity in the world.

It boasts over 6,500 marine species, each of which has a role to play in the success of this enormous, interconnected ecosystem.

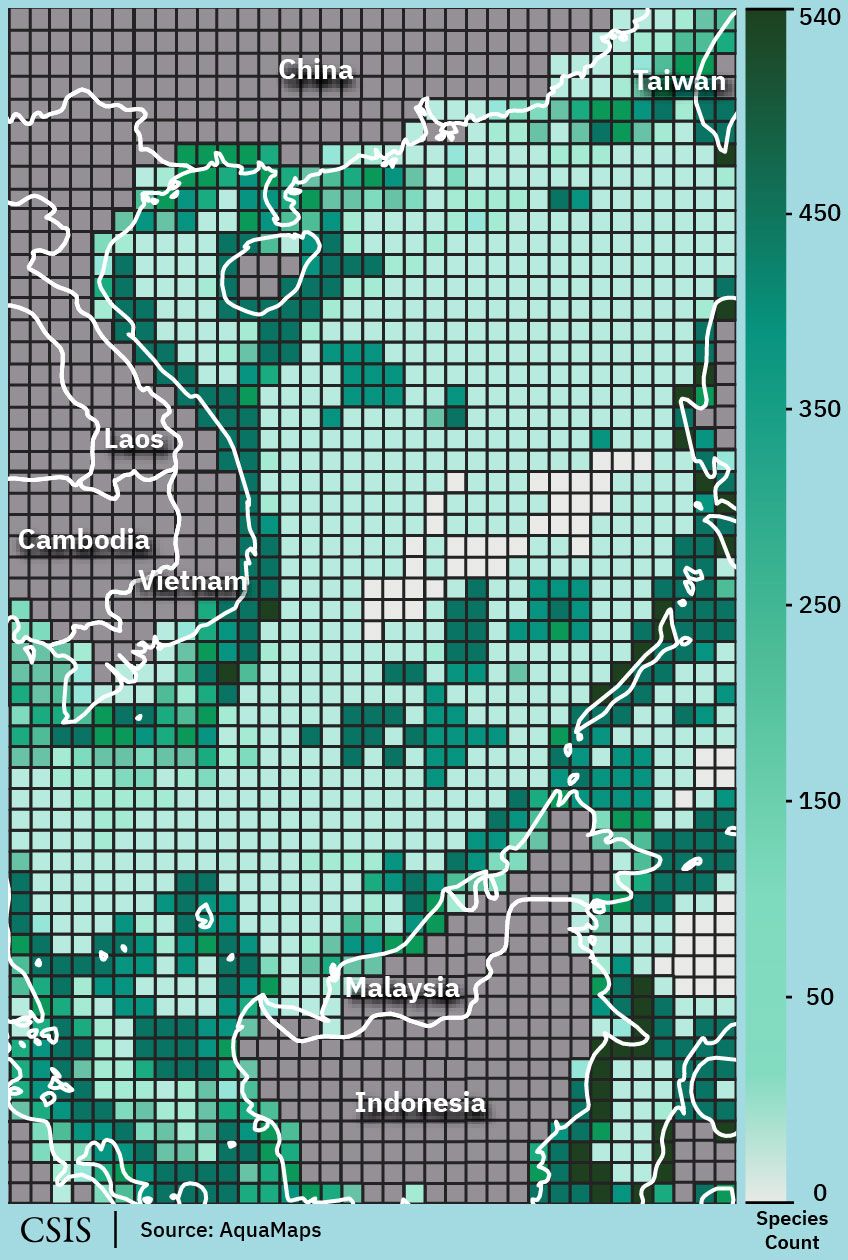

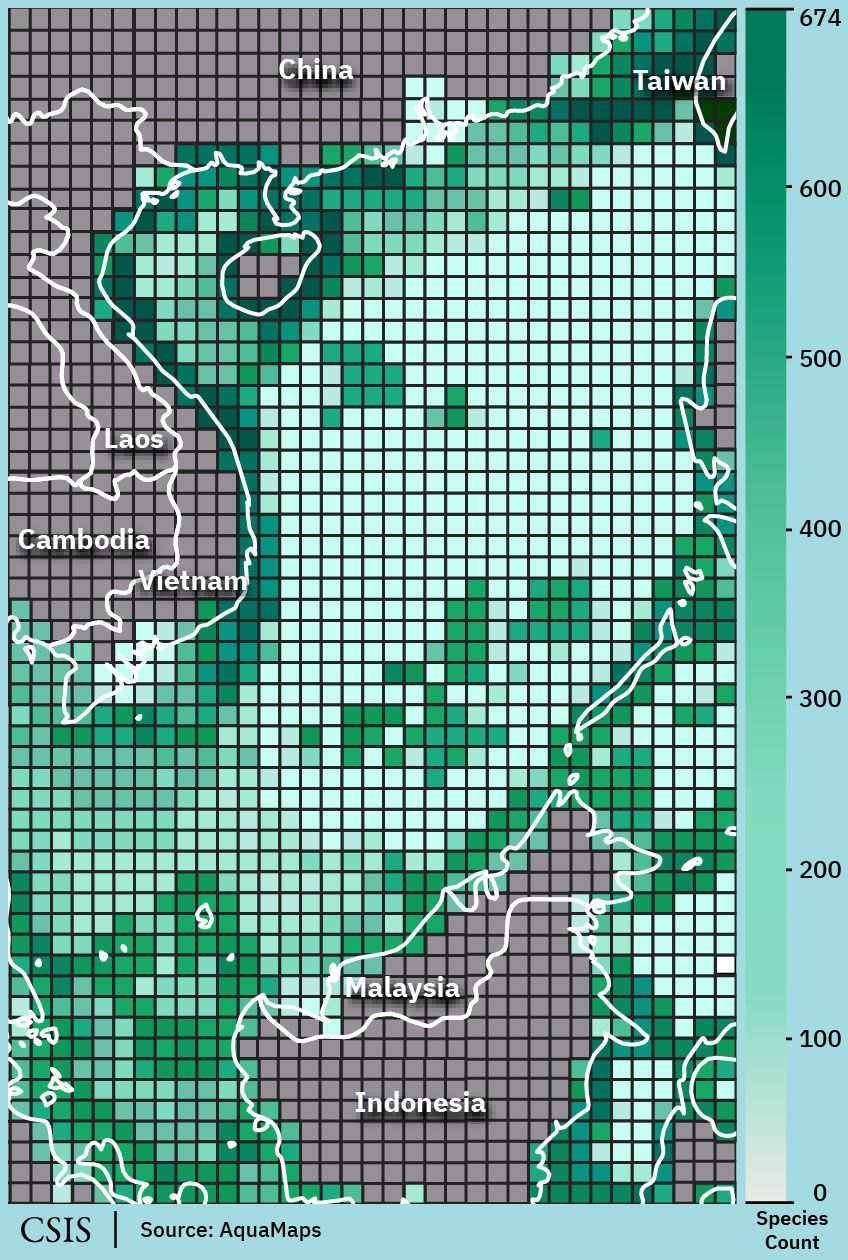

This map of the biodiversity of hard coral shows the density of species scattered throughout the South China Sea.

This map of the biodiversity of hard coral shows the density of species scattered throughout the South China Sea.

Coral

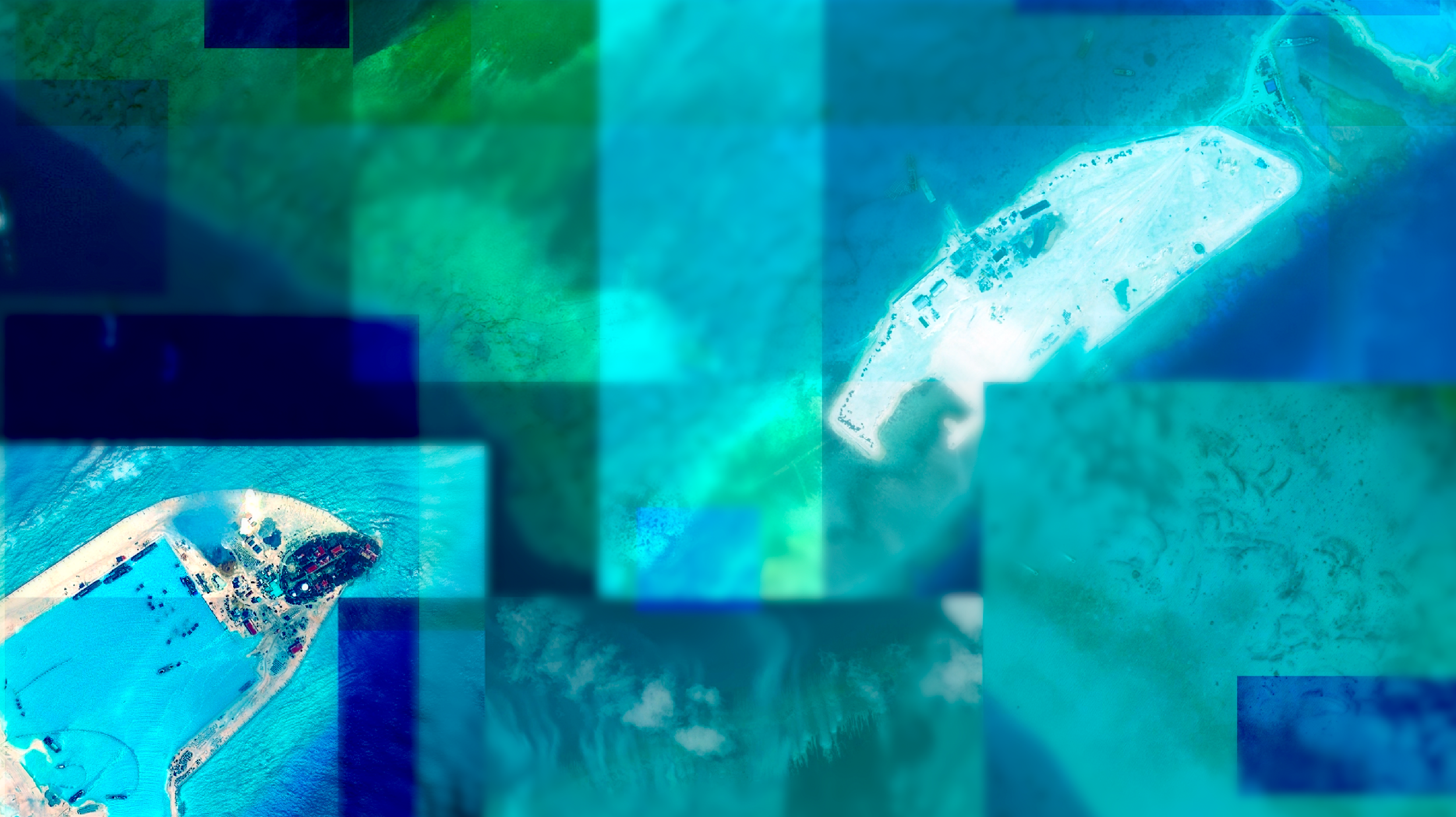

Coral reefs support nearly 25 percent of global marine life. Of the world’s 1,683 reef-forming coral species, 571 are found in the South China Sea.

Coral reefs are considered one of the most vital ecosystems in the South China Sea, providing food and shelter to thousands of species in their surrounding environment.

They are also one of the most threatened ecosystems in the region, with coral cover declining 16 percent per decade.

Fish

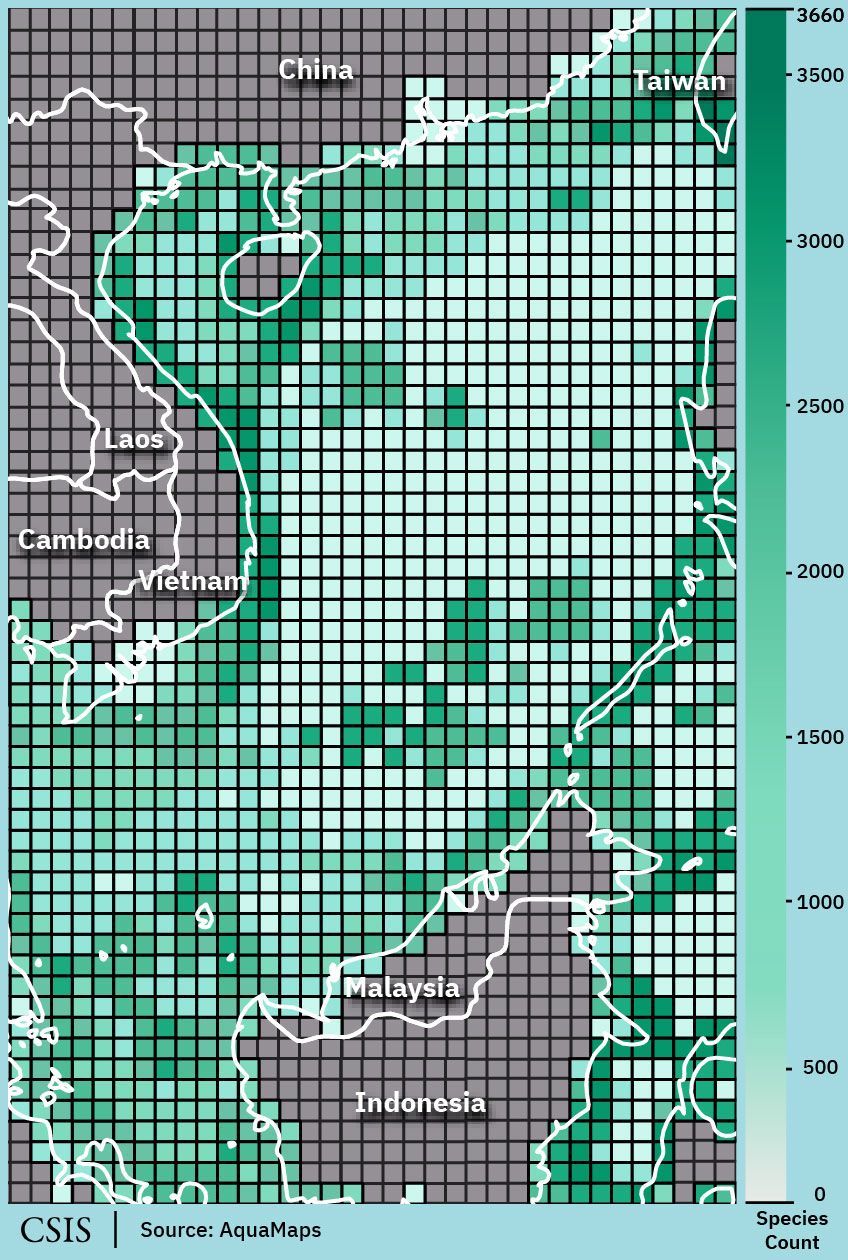

About 22 percent of the world’s fish species are found in the South China Sea, with coral reefs supporting a total of 3,790 species of fish. Pelagic fish such as tuna, also traverse the area. The exceptional variety of fish in the South China Sea make it a central hub for commercial fishing in the broader Indo-Pacific region. It ranks as one of the world’s top five fishing areas.

Biodiversity of Fish in the South China Sea

Biodiversity of Fish in the South China Sea

Bivalves

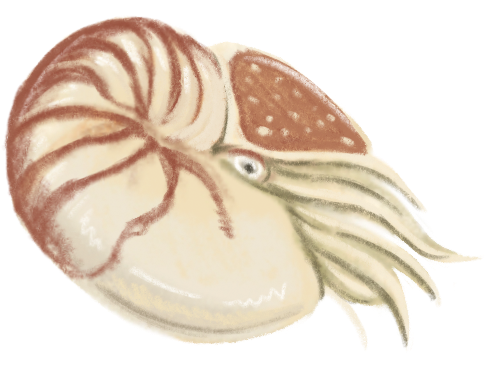

The South China Sea is also home to eight of the ten global species of giant clam. This includes the Tridacna gigas, the world’s largest shellfish. Giant clams are vital to the health of reef ecosystems. They serve as food and shelter for other animals, and act reef builders and shapers. They also counter eutrophication through water-filtering.

Biodiversity of Bivalves in the South China Sea

Biodiversity of Bivalves in the South China Sea

Sharks & Mammals

The South China Sea boasts a wide variety of larger species like sharks, rays, and marine mammals like dolphins and whales.

Other Species

It is also home to a myriad of other organisms that live in the water and along the ocean floor. Even species that have no commercial value play crucial ecological roles in maintaining the marine habitat that allows all species to thrive.

Humans

The South China Sea is a vital source of food and livelihoods for the countries surrounding it, which are home to around 1.87 billion people.

While some communities practice more sustainable fishing methods, the rise of large-scale industrial fishing has endangered large areas of the food web.

Geopolitical competition and poor resource management have put this vibrant ecosystem under threat, starting with its very foundation: the coral reefs themselves.

II. Reef Destruction in the South China Sea

Part 1: Dredging & Land Fill

To build outposts that support their competing claims in the South China Sea, claimants have engaged in dredging and land fill across the region. This has destroyed vast areas of the South China Sea’s coral reef ecosystems over the last 10 years.

Dredging: The removing of silt, sediments, and other materials from the seabed, often done in the South China Sea for the purpose of creating channels, harbors, or to gather material for landfill.

Land Fill: The creation of new artificial land with dredged seabed material.

Dredging can entirely remove essential reef substructures, causing irreparable and long-term changes to the overall structure and health of the reef.

Asia's largest heavy-duty self-propelled cutter and suction vessel in Lianyungang, China. | CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images

Asia's largest heavy-duty self-propelled cutter and suction vessel in Lianyungang, China. | CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images

From late 2013 to 2017, China used dredging to build out its artificial islands. Its cutter suction dredgers would slice into the reef and pump sediment through floating pipelines to shallow areas to deposit it as landfill. This process disturbed the seafloor, creating clouds of abrasive sediment that killed nearby marine life and overwhelmed the coral reef’s capacity to repair itself.

Dredging always damages the surrounding environment, but other claimants have a history of using less destructive dredging methods. Until recently, Vietnam had primarily used clamshell dredgers and construction equipment to scoop up sections of shallow reef and deposit the sediment on the area targeted for landfill.

This method is slower and causes less collateral damage to surrounding areas. However, it still destroys the coral reef where the sediment is extracted and deposited.

More recently, however, Vietnam has turned to cutter suction dredgers like China’s. This large-scale expansion of Vietnam’s South China Sea outposts remains ongoing and will have major consequences for the surrounding marine environment.

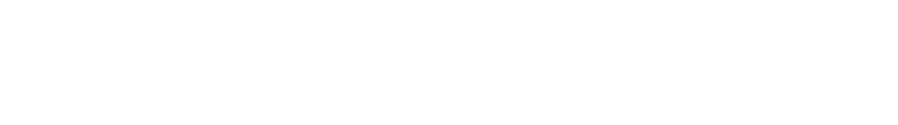

Commercial satellite imagery analysis undertaken by the CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) has revealed the approximate total area of coral reefs destroyed by China, Vietnam, and other claimants in the region.

The results show that China has caused the most reef destruction through dredging and land fill, burying roughly 4,648 acres of reefs.

From late 2013 to 2017, China used dredging to build out its artificial islands. Its cutter suction dredgers would slice into the reef and pump sediment through floating pipelines to shallow areas to deposit it as landfill. This process disturbed the seafloor, creating clouds of abrasive sediment that killed nearby marine life and overwhelmed the coral reef’s capacity to repair itself.

Dredging always damages the surrounding environment, but other claimants have a history of using less destructive dredging methods. Until recently, Vietnam had primarily used clamshell dredgers and construction equipment to scoop up sections of shallow reef and deposit the sediment on the area targeted for landfill.

This method is slower and causes less collateral damage to surrounding areas. However, it still destroys the coral reef where the sediment is extracted and deposited.

More recently, however, Vietnam has turned to cutter suction dredgers like China’s. This large-scale expansion of Vietnam’s South China Sea outposts remains ongoing and will have major consequences for the surrounding marine environment.

Commercial satellite imagery analysis undertaken by the CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) has revealed the approximate total area of coral reefs destroyed by China, Vietnam, and other claimants in the region.

The results show that China has caused the most reef destruction through dredging and land fill, burying roughly 4,648 acres of reefs.

The actual amount of reef destroyed by these practices is almost certainly greater than these estimates, which cannot account for damage in deeper areas.

Unfortunately, dredging and land fill are only half of the story of reef destruction in the South China Sea.

II. Reef Destruction in the South China Sea

Part 2: Giant Clam Harvesting

Scholars studying the environmental effects of dredging and land fill on coral reefs also discovered another destructive phenomenon: vast areas of coral reef damaged by giant clam harvesting.

The harvesting of giant clams for their remarkable shells has become popular in recent decades because of their resemblance to elephant ivory, which is now extremely difficult or illegal to obtain. The shells are typically worked into jewelry and statues and sold for high prices in China—as much as $106,000 per carved shell.

Giant clam harvesting was especially prevalent between 2012 and 2015 among fishers from the port of Tanmen on China’s Hainan Island. The surge coincided with government efforts to promote maritime activity in the South China Sea. President Xi Jinping visited Tanmen in 2013 and pledged support for fishers while urging them to “catch more big fish.”

Giant clams in Bolinao, Philippines. | David Greedy via Getty Images.

Giant clams in Bolinao, Philippines. | David Greedy via Getty Images.

Although local Hainan authorities attempted to crack down on the sale of giant clams in 2017, satellite imagery from 2019 shows that harvesting in the South China Sea persisted, even under the eye of the China Coast Guard. Giant clam products continue to be sold in China on the black market.

This increase in harvesting has led several species of giant clams to be classified as vulnerable. However, the method by which Chinese fishers have harvested these creatures is even more damaging, laying waste to large swathes of coral reef.

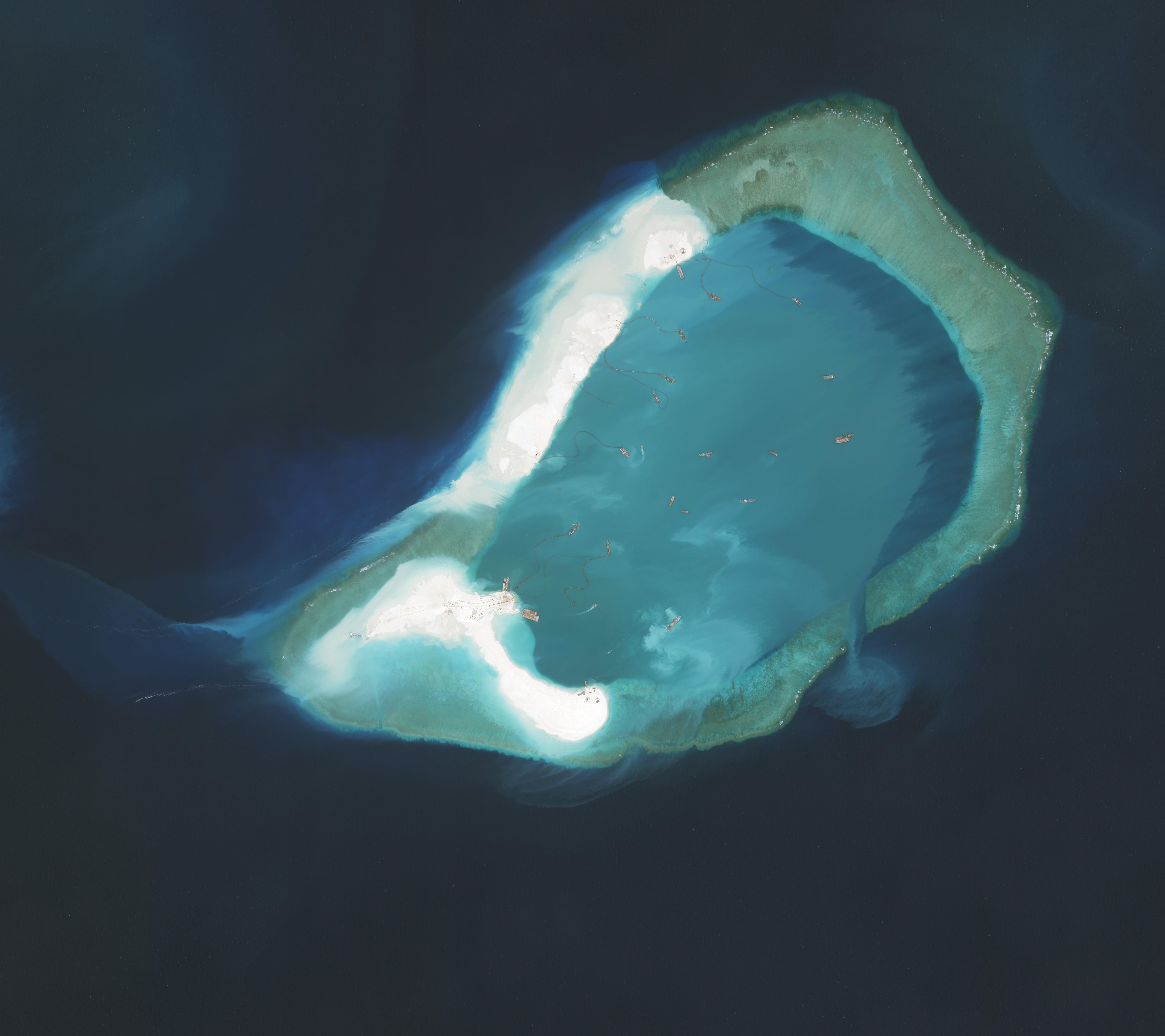

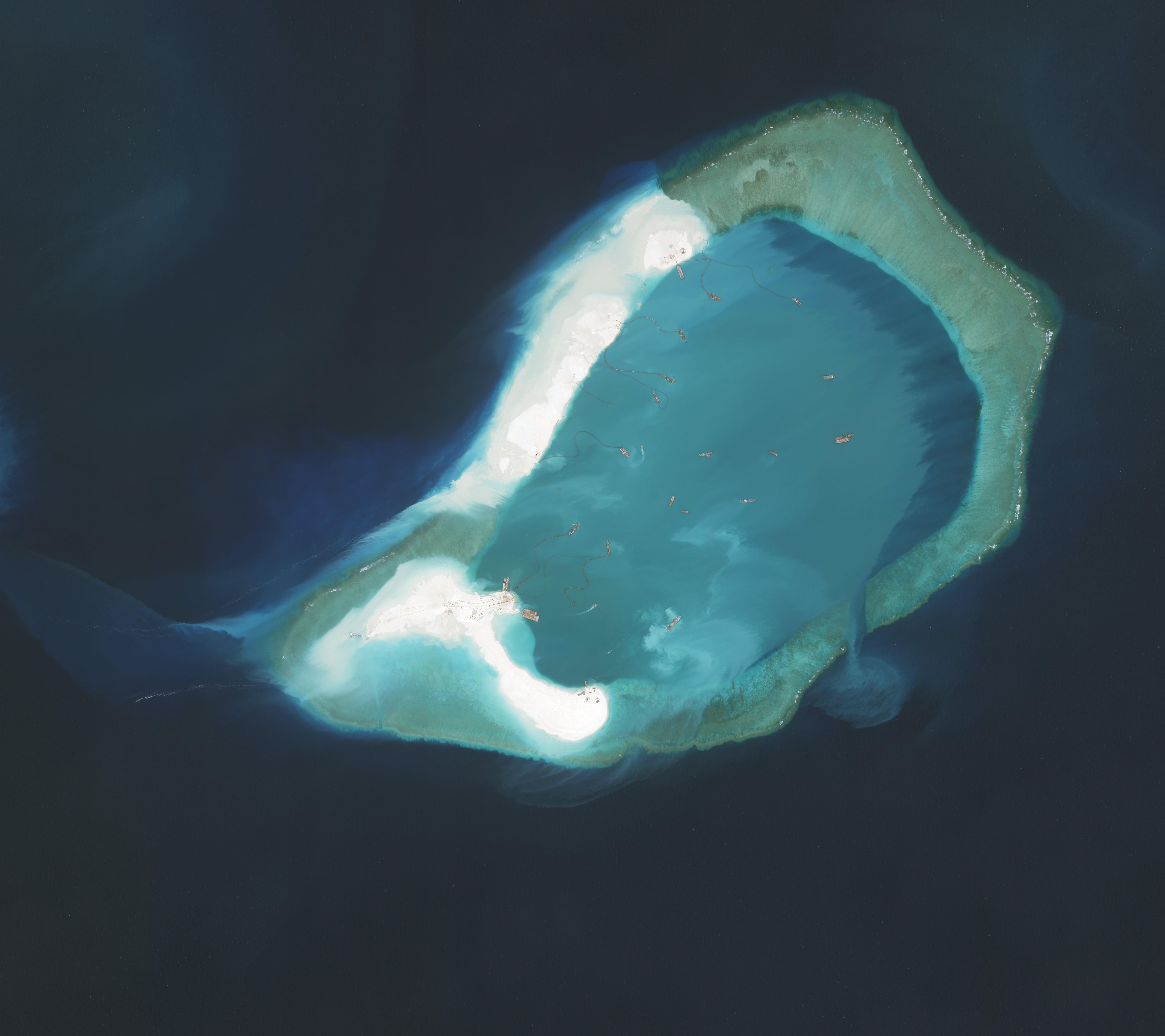

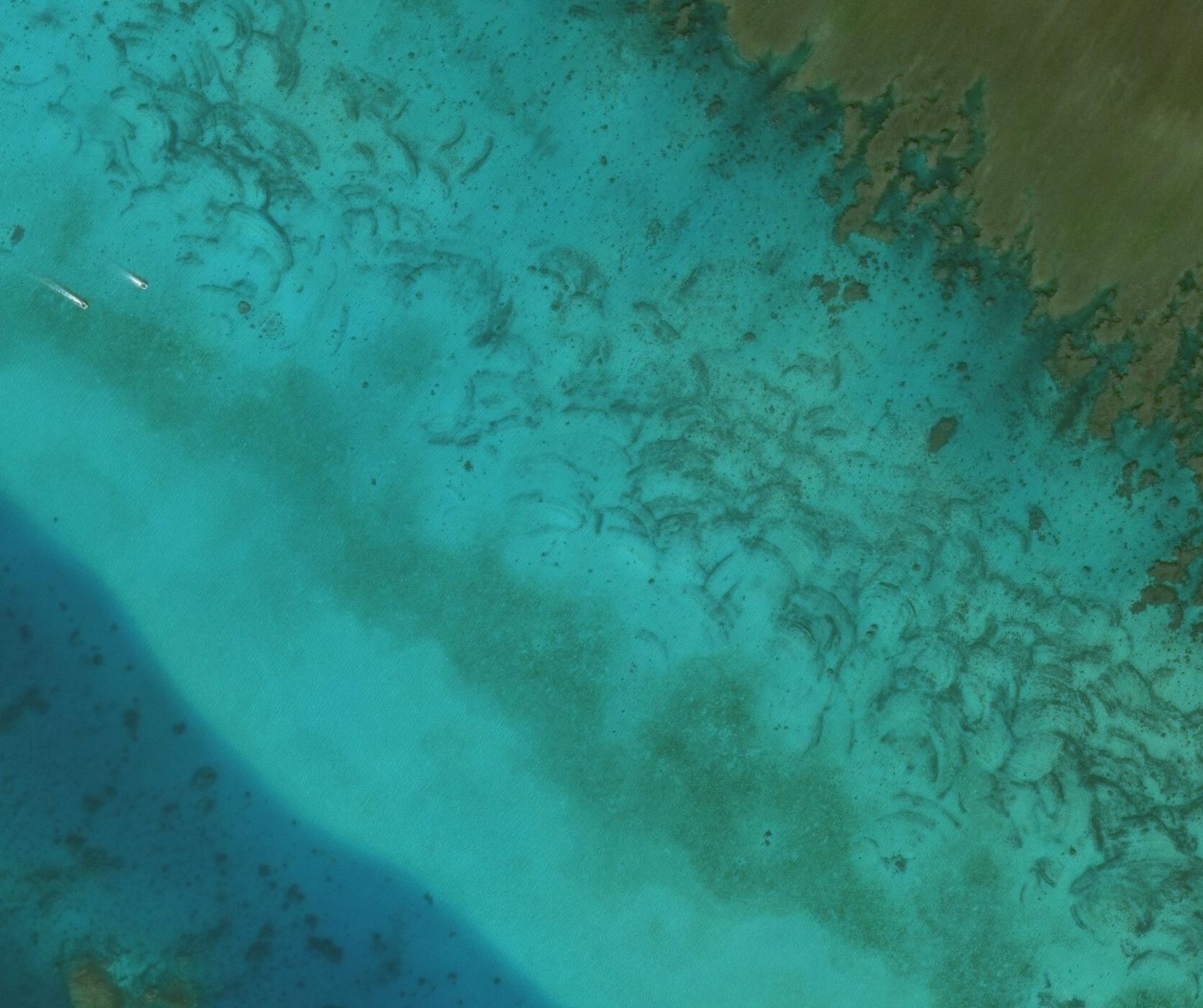

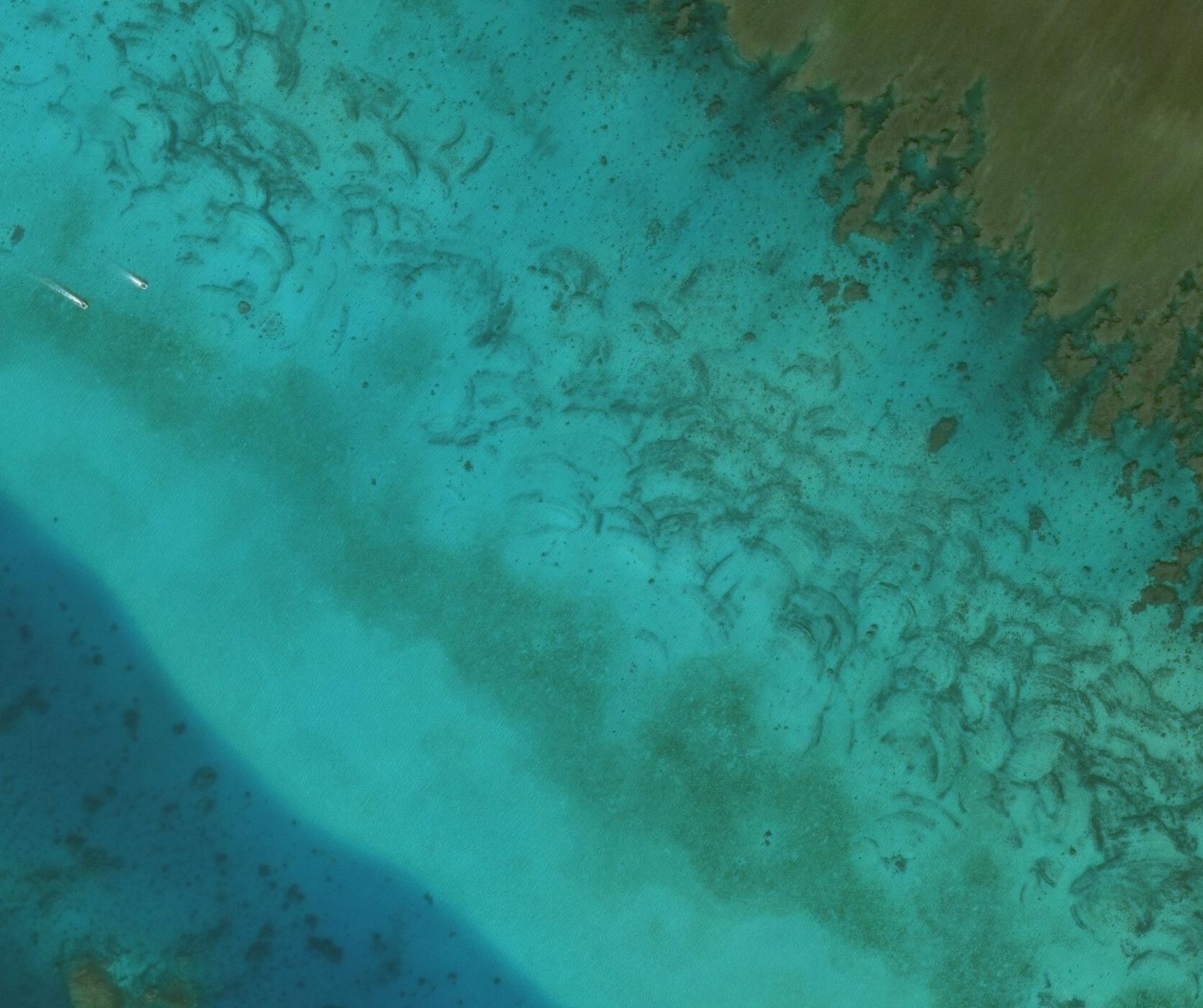

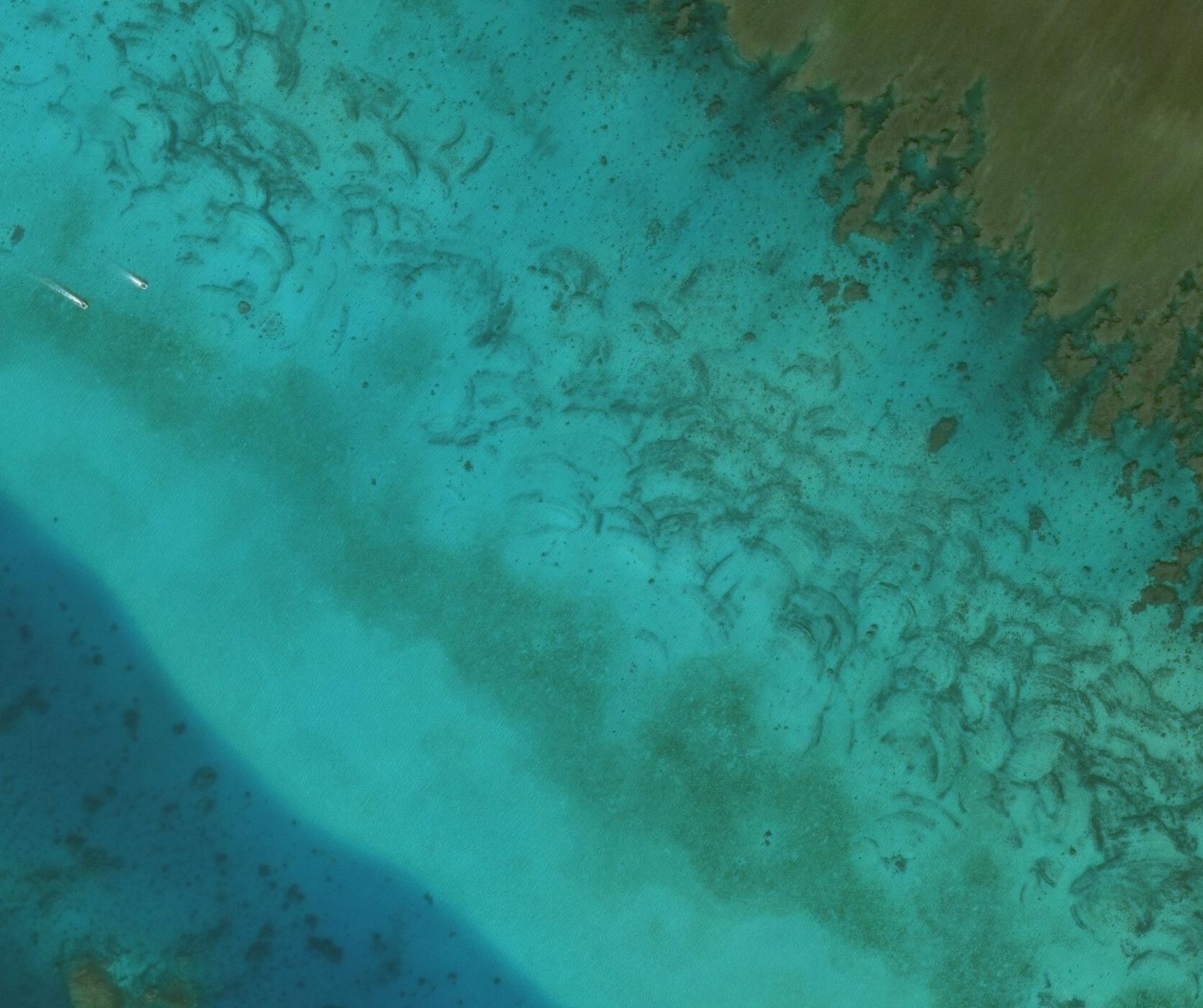

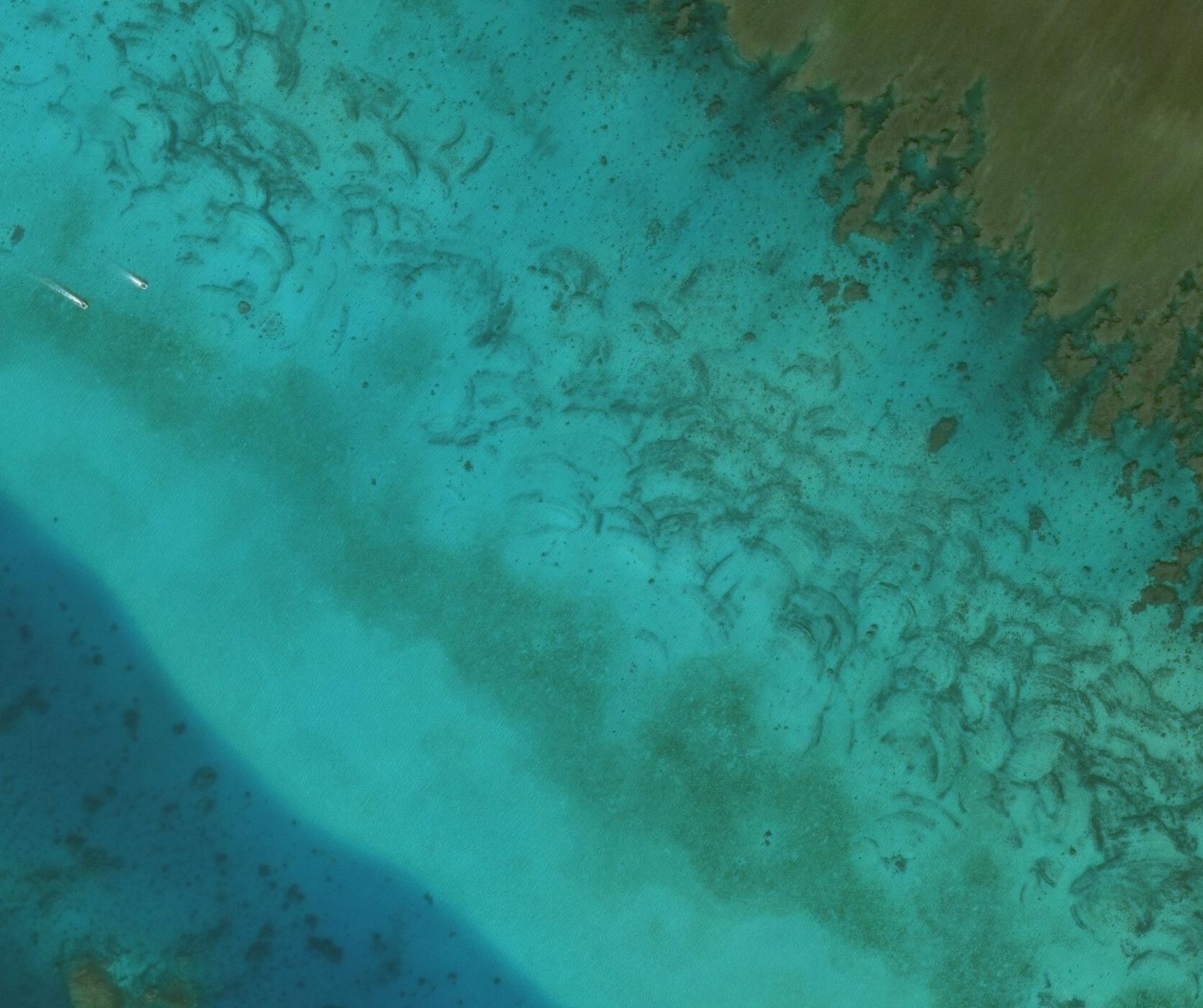

In satellite imagery of the South China Sea, many reefs show arc-shaped scars, which are created when fishers dig up reef surfaces by dragging specially made brass propellers in a semicircle around the anchor chain on the front of their boats.

This allows them to more easily harvest both live and dead clams attached to the reef.

Although fishers from the Philippines and Vietnam have a history of giant clam harvesting, only Chinese fishers are known to use this method.

AMTI analyzed commercial satellite imagery on a total of 181 occupied and unoccupied features of the South China Sea.

AMTI estimates that approximately 16,535 acres of reef have been damaged by Chinese giant clam harvesting.

Although local Hainan authorities attempted to crack down on the sale of giant clams in 2017, satellite imagery from 2019 shows that harvesting in the South China Sea persisted, even under the eye of the China Coast Guard. Giant clam products continue to be sold in China on the black market.

This increase in harvesting has led several species of giant clams to be classified as vulnerable. However, the method by which Chinese fishers have harvested these creatures is even more damaging, laying waste to large swathes of coral reef.

In satellite imagery of the South China Sea, many reefs show arc-shaped scars, which are created when fishers dig up reef surfaces by dragging specially made brass propellers in a semicircle around the anchor chain on the front of their boats.

This allows them to more easily harvest both live and dead clams attached to the reef.

Although fishers from the Philippines and Vietnam have a history of giant clam harvesting, only Chinese fishers are known to use this method.

AMTI analyzed commercial satellite imagery on a total of 181 occupied and unoccupied features of the South China Sea.

AMTI estimates that approximately 16,535 acres of reef have been damaged by Chinese giant clam harvesting.

A giant clam is seen on a reef at a marine sanctuary off the coast of Batangas province in the Philippines on April 11, 2023. | Dante Diosina Jr/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

A giant clam is seen on a reef at a marine sanctuary off the coast of Batangas province in the Philippines on April 11, 2023. | Dante Diosina Jr/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Giant Clams spew water as a traditional fisherman passes by a small sanctuary on January 23, 2004 near Bolinao in the Northern Philippines. | David Greedy/Getty Images

Giant Clams spew water as a traditional fisherman passes by a small sanctuary on January 23, 2004 near Bolinao in the Northern Philippines. | David Greedy/Getty Images

A carved giant clam on display at the 9th China luxury goods trade fair in Haikou, in China's southern Hainan Province. | STR/AFP via Getty Images

A carved giant clam on display at the 9th China luxury goods trade fair in Haikou, in China's southern Hainan Province. | STR/AFP via Getty Images

Recent evidence from the Philippines suggests that China has begun using alternative methods of giant clam harvesting.

In 2019 near Scarborough Shoal, a method seemingly adapted from salvagers was captured on film. A high-pressure water pump is used to quickly suck sediment from the seabed. This extracts giant clams while also destroying the seabed and sending abrasive sediment drifting through nearby areas.

This method of clam harvesting has likely been employed beyond Scarborough Shoal. The Armed Forces of the Philippines Western Command (WESCOM) released a report in September 2023 showing severe environmental damage at Iroquois Reef and Sabina Shoal, which it says was caused by Chinese maritime militia.

Satellite imagery of these features shows no scarring on shallow reef surfaces, so damage photographed by the Armed Forces of the Philippines likely occurred in the deeper lagoons. Currently, the only previously observed cause of such damage in the South China Sea is the water pump method of giant clam harvesting used at Scarborough in 2019.

The lagoons at Sabina Shoal, Iroquois Reef, and Scarborough Shoal account for about 41,354 acres of reef. The full extent of damage in these lagoons remains to be assessed by marine experts. If the damage was found to be extensive, it could bring the total reef area damaged by Chinese giant clam harvesting to 57,889 acres, or over 90 square miles.

Over 20 percent of maritime features in the South China Sea have sustained damage from giant clam harvesting.

Since clam harvesting on deeper reef structures cannot be monitored by satellite, there is no telling how many other lagoons have been damaged in the same way. Only additional on-site investigation can reveal how many of the remaining 2,159,000 acres of unoccupied reef in the South China Sea have been affected.

The harvesting of giant clams plays a unique role in the destruction of the South China Sea’s coral reefs. But they are far from the only species threatened by overharvesting in the region.

III. Overfishing in the South China Sea

The South China Sea plays a critical role both as a food source and as a provider of economic opportunity and stability. Twelve percent of the global fish catch comes from the South China Sea.

Fishing provides livelihoods for at least 3.7 million people in the region with 55 percent of global fishing vessels found there.

The scale of this economic and nutritional dependence has led to fisheries in the South China Sea being overexploited. Efforts to responsibly manage them have been thwarted by geopolitical tensions and competing maritime claims for years.

Fishermen set off firecrackers on fishing boats before setting sail for fishing on August 16, 2023 in Quanzhou, Fujian Province of China. | Wang Dongming/China News Service/VCG via Getty Images

Fishermen set off firecrackers on fishing boats before setting sail for fishing on August 16, 2023 in Quanzhou, Fujian Province of China. | Wang Dongming/China News Service/VCG via Getty Images

The lack of clear maritime jurisdiction in the region makes it difficult to define what constitutes illegal fishing. As a result, a substantial portion of fishing in the South China Sea goes unregulated or unreported.

To compensate for the lack of reliable data on fishing activity, the Sea Around Us project at the University of British Columbia developed a methodology to estimate fishing intensity.

By combining insights from national reported fish catch figures with reconstructive research into local fishing practices and archival records, Sea Around Us is able to estimate the scale of unreported fish catch. It also reconstructs more detailed data about the breakdown of fish catches by location, flag state, species, and fishing method.

Data from Sea Around Us on fish catch in the South China Sea show that after sharp increases since the 1950s, fish catch has remained relatively stagnant since the mid-1990s. This stagnation, despite continuing increases in fishing effort, indicates that fish stocks are overexploited.

Along with an overall increase in fishing effort, the way that most fish in the South China Sea are caught has changed over time. Fishing can be divided into four types: , , , and

Industrial fishing has grown substantially, and with it, bottom trawling, which has been the dominant fishing method in the South China Sea since the 1980s.

Bottom trawlers drag large, weighted nets along the seabed, catching everything in their path, including fish, marine mammals, plants, and turtles. The ropes and weights that drag along the ocean floor destroy seabed ecosystems by ripping up coral and sponges and stirring up sediment.

As with trawling, China and Vietnam account for the largest share of overall fish catch in the South China Sea.

The lack of clear maritime jurisdiction in the region makes it difficult to define what constitutes illegal fishing. As a result, a substantial portion of fishing in the South China Sea goes unregulated or unreported.

To compensate for the lack of reliable data on fishing activity, the Sea Around Us project at the University of British Columbia developed a methodology to estimate fishing intensity.

By combining insights from national reported fish catch figures with reconstructive research into local fishing practices and archival records, Sea Around Us is able to estimate the scale of unreported fish catch. It also reconstructs more detailed data about the breakdown of fish catches by location, flag state, species, and fishing method.

Data from Sea Around Us on fish catch in the South China Sea show that after sharp increases since the 1950s, fish catch has remained relatively stagnant since the mid-1990s. This stagnation, despite continuing increases in fishing effort, indicates that fish stocks are overexploited.

Along with an overall increase in fishing effort, the way that most fish in the South China Sea are caught has changed over time. Fishing can be divided into four types: artisanal , industrial , recreational, and subsistence .

Industrial fishing has grown substantially, and with it, bottom trawling, which has been the dominant fishing method in the South China Sea since the 1980s.

Bottom trawlers drag large, weighted nets along the seabed, catching everything in their path, including fish, marine mammals, plants, and turtles. The ropes and weights that drag along the ocean floor destroy seabed ecosystems by ripping up coral and sponges and stirring up sediment.

As with trawling, China and Vietnam account for the largest share of overall fish catch in the South China Sea.

IV. The Future of the South China Sea

While governments work to resolve territorial and maritime disputes, equal attention must be given to the South China Sea’s declining marine environment.

The damage has been directly caused by human activity that is allowed, supported, and initiated by coastal states. Therefore, coastal states must also be at the center of efforts to stop destructive practices and safeguard marine ecosystems before it is too late.

China has played the largest role, destroying or severely damaging at least 21,183 acres of coral reef—and likely much more—through island expansion and giant clam harvesting. It also dominates the industrialized overfishing that has devastated South China Sea fish stocks.

Basket boats sit moored in Tan Quang harbor in Quang Nam province, Vietnam, on Wednesday, June 26, 2019. | Maika Elan/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Basket boats sit moored in Tan Quang harbor in Quang Nam province, Vietnam, on Wednesday, June 26, 2019. | Maika Elan/Bloomberg via Getty Images

But China is not alone. Vietnam has also played an outsize role in reef destruction and overfishing. And though other claimants have played smaller parts, they all share in the responsibility to maintain one of the world’s most diverse marine environments.

For the South China Sea to be saved, these practices must change.

Urgent efforts within and among regional governments, researchers, and environmental organizations are needed to responsibly manage these waters and secure the lives and livelihoods of all who rely on them.

Made possible by the generous support of the U.S. Department of State's Global Engagement Center

To view a translated PDF of this report, please click one of the following: Indonesian, Japanese, Malaysian, Tagalog, Thai, Traditional Chinese, Vietnamese

Authors

Harrison Prétat, Deputy Director and Fellow, CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

Monica Sato, Research Associate, CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

Tabitha Mallory, China Ocean Institute

Hao Chen, China Ocean Institute

Gregory B. Poling, Director, CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

Special Thanks

John McManus, Chiara Zambrano, and Josiah Gottfried

iDeas Lab Story Production

Editorial, design by: Sarah B. Grace

Editorial assistance & research by: Claire Smrt

Data visualizations by: Fabio Murgia & Sarah Grace

Illustrations by: Gab K. De Jesus

Development support by: Mariel de la Garza & Gab K. De Jesus

Design assistance & production by: Gina Kim

Copyediting support by: Katherine Stark

Photo Credits

Cover: Satellite imagery by AMTI, Maxar Technologies, and Planet Labs | Design by Sarah B. Grace