Electric Avenues:

Localizing Electric Vehicle Supply Chains

China dominates the electric vehicle battery race.

Can the United States catch up?

During the pandemic, business closures, staff shortages, and lockdowns disrupted the flow of raw materials and finished goods into the United States and other nations. Two years later, Russia invaded Ukraine, cutting off an estimated 80 percent of gas supplies to the European Union.

The back-to-back crises demonstrated an urgent need to build more resilient supply chains. One such supply chain is the production of electric vehicles (EVs)—widely regarded as essential to decarbonizing America’s transportation sector.

U.S. policymakers have adopted an ambitious plan to move EV production away from China and toward the United States, its neighbors, and its allies. These plans are driven by fears of overreliance on China in this key sector, especially in a context of rising geopolitical competition between the two countries.

But can the United States compete with China, which leads the world in not just EV production but also in most green technologies? And by taking the time to localize production, does the United States risk delaying EV uptake and jeopardizing the United States’ ambitious climate goals?

From Minerals to Motorways

EV use is on the rise. To meet global demand, the world needs batteries for those vehicles and the rare-earth minerals that power them.

Global demand for EV batteries increased by over 700 percent from 2015 to 2021. This rising demand has put enormous pressure on the supply of rare-earth metals such as lithium, manganese, and cobalt. For countries that want to play a role in this booming market, access to these materials has become an important geopolitical problem.

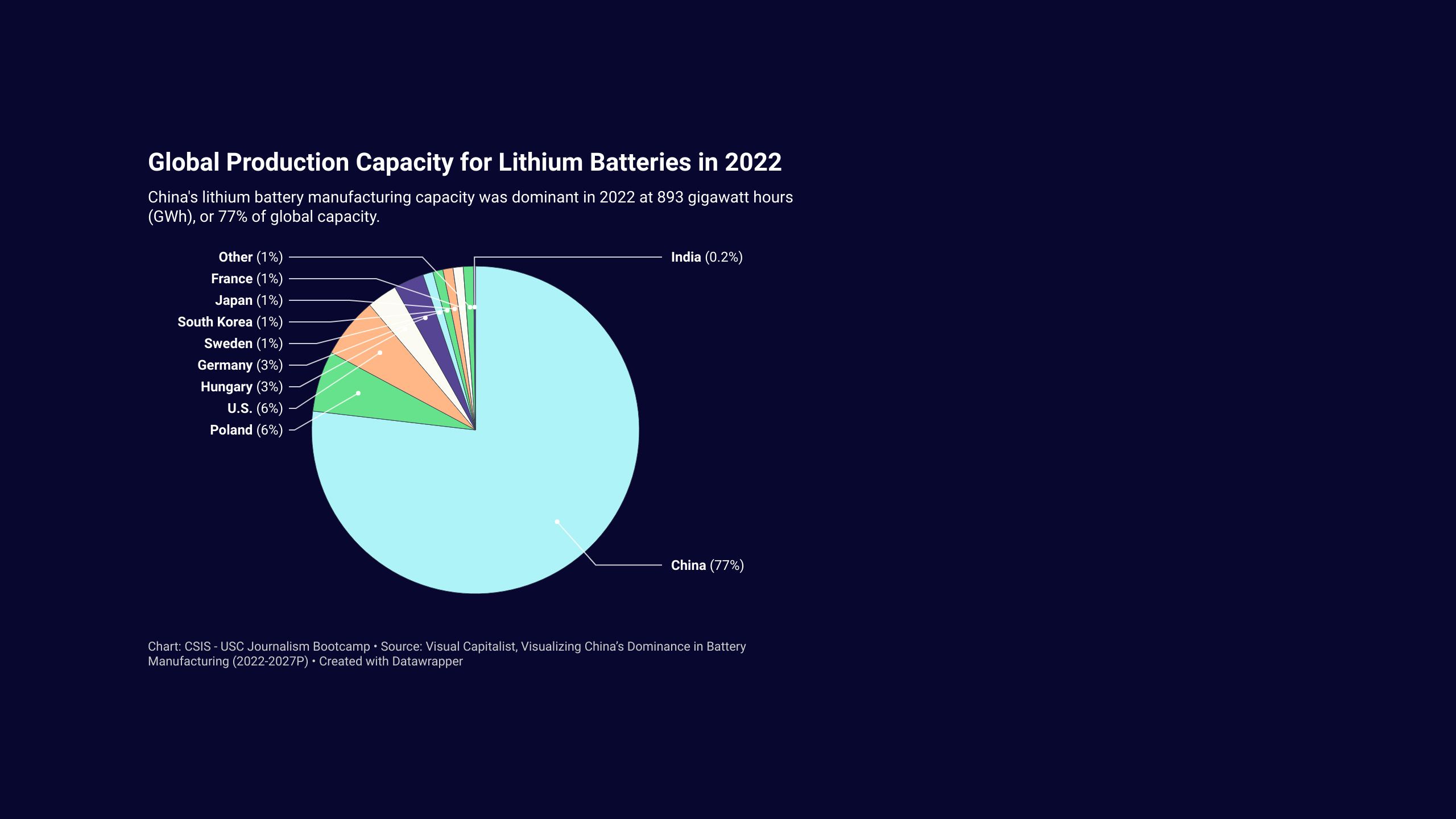

Currently, much of the global EV battery market is dependent on China. The country’s economy is built around a strong industrial sector, and in recent years it has put particular emphasis on manufacturing in green technologies.

China dominates not just EV battery manufacturing but also access to the relevant raw materials worldwide. A majority of the world’s rare-earth mineral mines are owned by China, and 85 percent of minerals mined around the world are processed in China.

Lithium, a vital component in EV batteries, is a key example of this.

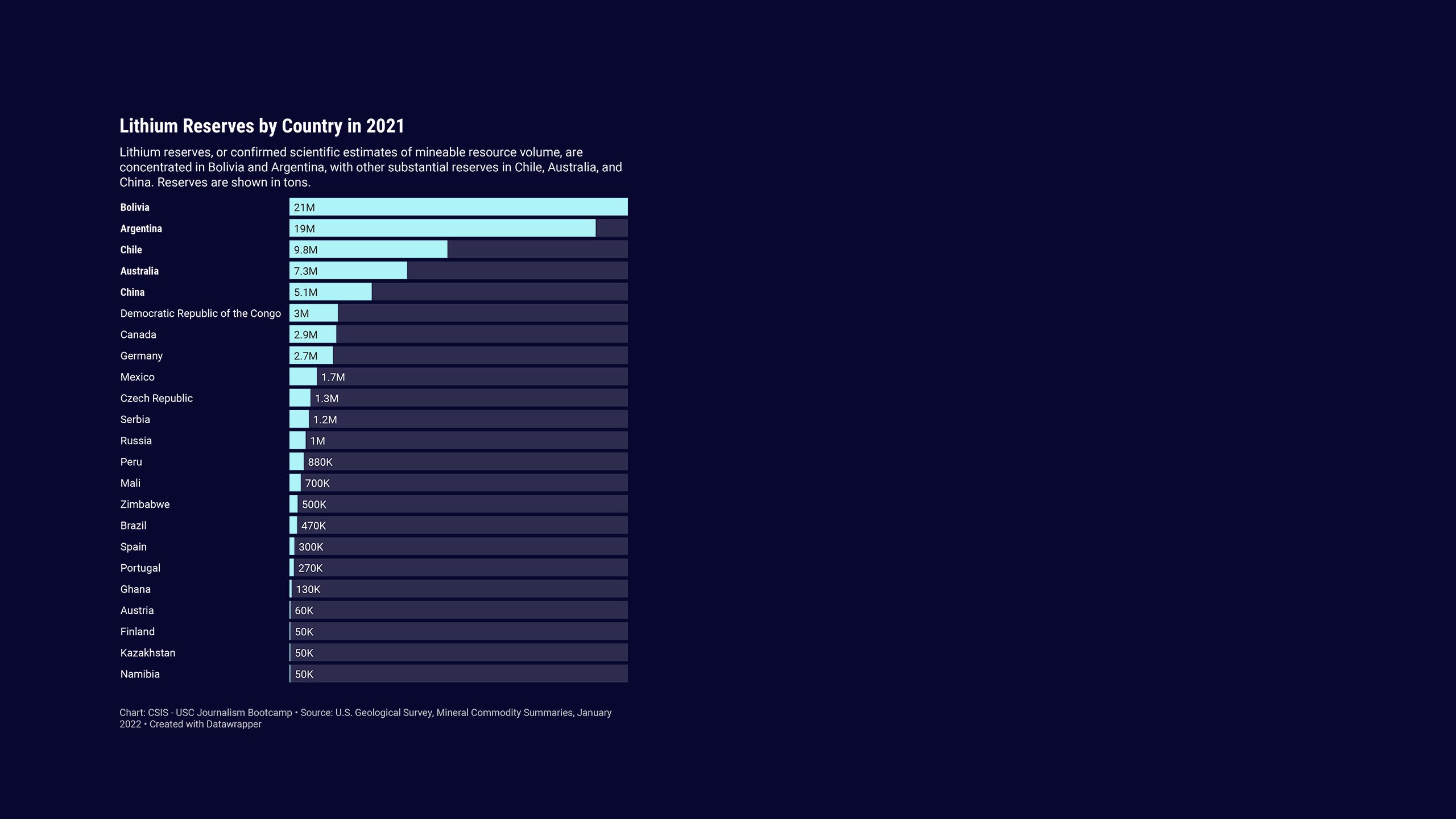

The bulk of the planet’s lithium reserves are in South America, Australia and China, but not all of those reserves are easily accessible.

While Bolivia has the world’s largest lithium reserves, the country is outside of the top five producers of the vital mineral. That may soon change; YLB, Bolivia’s state-owned mining company, recently signed a billion dollar agreement with Chinese companies to work on exploiting those reserves.

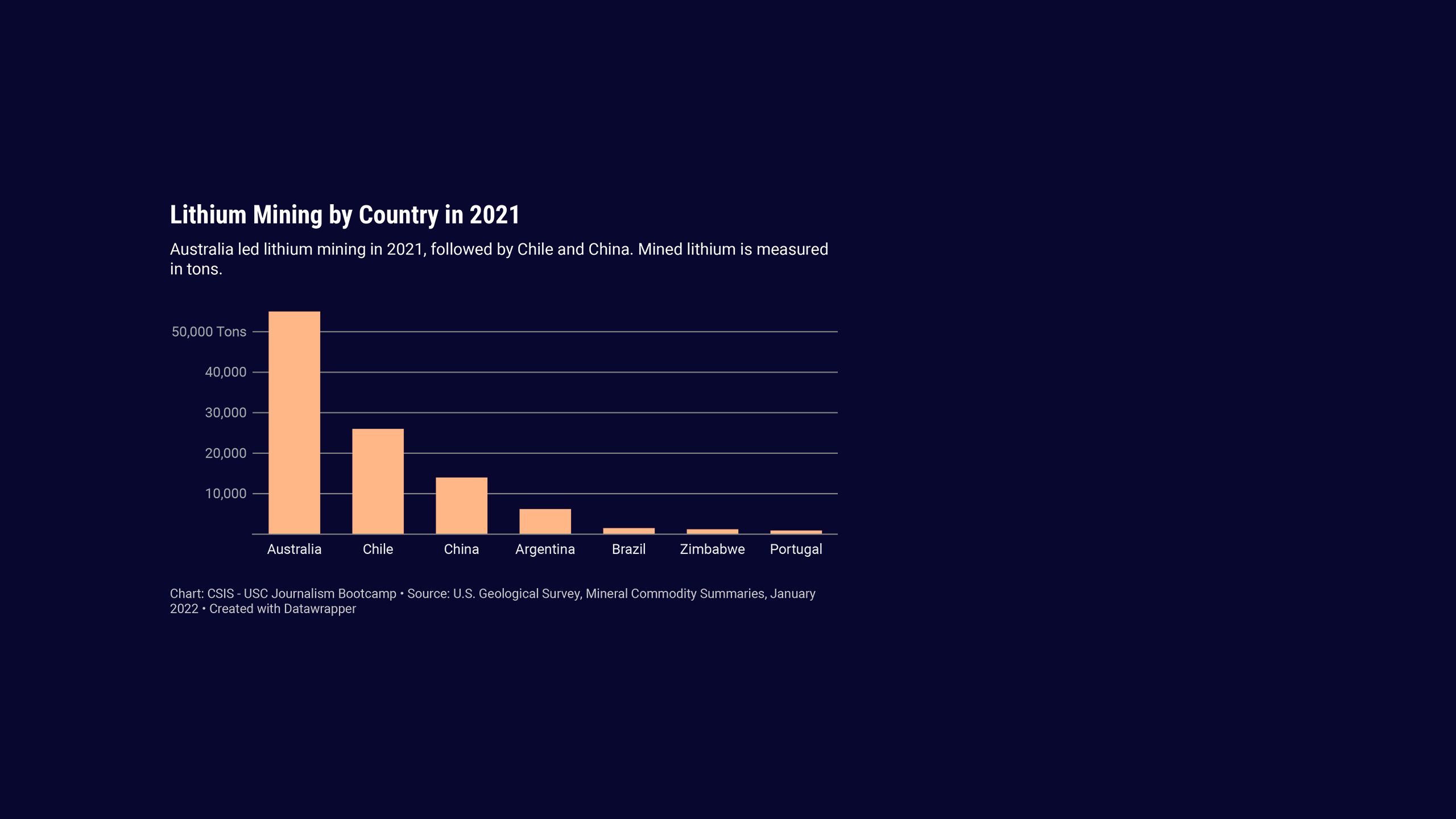

Although lithium reserves and mining are spread across the globe, there’s no competition when it comes to production; China is well ahead of the rest of the world.

It’s not just in production that China dominates. China is also over half the worldwide market for electric vehicles.

U.S. Incentives

The Biden administration has created significant incentives for American consumers to purchase EVs and for American companies to manufacture them domestically. The opportunity to both transform the country’s economy and simultaneously weaken China’s economy—and deny China’s near-monopoly—motivated this shift.

Inflation Reduction Act

Last August, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) implemented a tax credit of up to $7,500 when buying an electric car with a market price below $55,000. Part of that tax credit is only accessible if the car undergoes final assembly in North America. Currently, half the car has to be assembled on the continent, but the percentage required is set to increase year-on-year.

The IRA also added incentives to replace medium-duty vehicles such as school buses and heavy-duty vehicles such as garbage trucks with zero-emission vehicles.

These incentives are aimed at cleaning up the transportation sector, which is the country’s leading source of greenhouse gas emissions. But a transition to EVs will require a great deal of enabling infrastructure to be successful.

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), passed in November 2021, targeted improvements in national infrastructure in many forms, among them the future of green transportation.

The IIJA provided $7.5 billion toward the cross-country installation of EV charging stations, which will help to make EVs more convenient and appealing for consumers. It also provided $6 billion in funding for initiatives to manufacture and recycle advanced batteries and their components domestically. If successful, this initiative will ensure that domestic battery manufacturing is better able to keep up with American demand for EVs.

The goal with these actions is to fundamentally retool America’s economy to compete in the growing market for EVs and other green technologies. Climate change helped spark this movement, and economic opportunity fanned the flames, but those are not the only factors keeping this fire alight. The drive toward EVs is also an important part of a broader reevaluation of how trade and national security intersect.

Rethinking Trade

For much of the last century, U.S. trade policy was built on a consensus around lowering trade barriers and opening markets. “Historically, trade policy was focused on the assumption that freer, easier, cheaper trade was a major benefit,” says Emily Benson, director of the Project on Trade and Technology at CSIS.

This openness extended to the U.S.-China relationship, with the United States acting as a primary customer for China’s rapidly growing industrial base. More recently, however, the threat of a weakened industrial sector and competition with China have caused public opinion of the U.S.-China economic relationship to sour rapidly, and U.S. policymakers have become open to a more adversarial approach.

U.S. President Joe Biden speaks at the 2022 North American International Auto Show in Detroit, Michigan. | Mandel Ngan / AFP via Getty Images

U.S. President Joe Biden speaks at the 2022 North American International Auto Show in Detroit, Michigan. | Mandel Ngan / AFP via Getty Images

After the threat of trade wars loomed during the Trump administration, the Biden administration has taken a more targeted approach to competing with China. This includes not only efforts to encourage onshoring, such as the IRA and the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act, but also policies to restrict U.S. and allied companies from doing business with China in key technology areas. For example, in October 2022, the Biden administration announced export controls on advanced semiconductor technology, targeting China’s access to the hardware used for artificial intelligence and other advanced computing.

These laws allocate millions of dollars into domestic manufacturing funding and incentives. Policymakers have a variety of reasons for pursuing these changes, but they all push toward the same end of making the U.S. economy less dependent on Chinese manufacturing, especially in high-tech sectors.

"Jobs, Jobs, Jobs"

As the Biden administration approaches the 2024 election cycle, it is looking to these onshoring efforts to deliver economic wins to important political battlegrounds. According to Lachlan Carey of the Rocky Mountain Institute, a large swath of semiconductor and other green technology manufacturing facilities are set to be built in rust belt and coal mining states impacted by deindustrialization. In these states, where many voters are not highly motivated by climate concerns, these economic benefits could play a key role in winning support for Biden’s agenda.

While moving away from fossil fuels and toward green energy has long been viewed as a job-killer, the IRA is part of the Biden administration’s attempt to reframe this transformation as being good for American workers. While this frame was not enough to earn any Republican votes for the IRA, it remains to be seen if this strategy will reap any political benefits going forward.

Security Threats

The economic concerns driving the nearshoring push are about more than just voters’ pocketbooks. According to Benson, there is a growing concern in Washington that economic dependency on China in key sectors is a threat to U.S. national security. “If we rely on one foreign entity or country for the majority of inputs to a given supply chain, does that create a vulnerability? If so, how do we build resiliency to avoid some of the pitfalls of an over-reliance on a single market?”

These concerns reflect a broader overlap between trade and national security for policymakers. These concerns do not end at general concerns about vulnerable supply chains; they also include cybersecurity and other potential threats.

For example, a growing number of cybersecurity experts warn that EV chips pose a malware threat to the American public. Stuart Madnick, a computer scientist and professor from MIT specializing in information technology, affirms the possibility of car technology causing vulnerabilities in domestic security. “Imagine the car starts driving erratically,” Madnick told the Wall Street Journal. “That is well within the realm of feasibility.”

"Are we building a supply chain that's good for national security? If we rely on one foreign entity or country for the majority of inputs to a given supply chain, does that create a vulnerability? If so, how do we build resiliency to avoid some of the pitfalls of an over-reliance on a single market?"

Decoupling from China could not only give U.S. actors a greater hold of American information but could also eliminate security concerns by reducing the country’s overall economic reliance on Chinese manufacturing.

Human Rights Concerns

The Chinese Communist Party has faced numerous accusations of forced labor, particularly the government’s mistreatment of Uyghur people. According to an investigation by the New York Times, lithium batteries and other green energy products tied to China’s Xinjiang province have been linked to forced labor camps targeting the Uyghur ethnic minority.

“Up to 2 million, if not more, ethnic Uyghurs in Western China were living in conditions that also included forced labor. Industries that Uyghur labor was involved in included solar panels and mining—which play a substantial role in the climate transition,” said CSIS Senior Fellow Erin Murphy.

Uyghurs, Tibetans, Hongkongers and Taiwanese demonstrators protest in front of the White House. | Nicholas Kamm / AFP via Getty Images

Uyghurs, Tibetans, Hongkongers and Taiwanese demonstrators protest in front of the White House. | Nicholas Kamm / AFP via Getty Images

The Biden administration passed the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act in 2021 as a response to the conditions faced by millions of Uyghurs. The act blocks the import of many products produced in the regions linked to forced labor. Notably, the region is one of the world’s leading producers of polysilicon, a key component in solar panels.

Taken together, these issues offer incentives for American policymakers across the political spectrum to invest in manufacturing EV batteries domestically. It is an industry that China may have bet on first—with a comparative export advantage—but the United States seems determined to boost its own capabilities. The transition could bring economic and security benefits but also comes with domestic and diplomatic challenges, including the risk of stalling broader climate goals.

Revving up American EV Manufacturing

Electric Avenues

Investing in American EV battery manufacturing has the potential to address both environmental and economic problems. The Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrated the fragility of U.S. supply chains. “It’s when we see supply side shocks to the system like we saw during Covid, like we saw from Putin's invasion of Ukraine, that we really notice the fragility of the supply chain,” Carey says. “So, by investing in manufacturing capacity here at home . . . amongst our neighbors [and] allies, what we’re doing is improving the resiliency of the supply chains and their ability to respond smoothly to the shocks.”

President Biden has long emphasized the economic benefits of producing clean energy technologies, such as EVs, in the United States. In 2021, Biden said, “When I think about the threats of hurricanes and global warming . . . I think one thing—I think of jobs, jobs, jobs.”

The United States is indeed well positioned to become a dominant player in EV manufacturing. “You’re already seeing a lot of [EV] factories located in the U.S.,” says Carey, “and that's because . . . the U.S. has historically had strength in the automobile manufacturing industry.”

Carey adds that there is a clear-cut environmental upside to localizing EV manufacturing. “On average,” he says, “the U.S. is much less carbon-intensive in its industrial processes than most developing nations.”

Biden’s IRA has generated enthusiasm even from fossil fuel companies eager to gain a foothold in America’s green hydrogen market. “We end up in this remarkable position where unbeknownst to many, you had fossil fuel producers lobbying Mitch McConnell, the Senate minority leader . . . to pass the most significant climate change bill in history,” says Carey.

Ford Motor Company's electric F-150 Lightning on the production line in Dearborn, Michigan. | Jeff Kowalsky / AFP via Getty Images

Ford Motor Company's electric F-150 Lightning on the production line in Dearborn, Michigan. | Jeff Kowalsky / AFP via Getty Images

Background Music via Artlist.io - Electricty by Ian Post

Changing Gears

Still, the US faces a number of major hurdles in localizing the production of EV batteries and other green technologies. First, the cost will be steep. A Bloomberg report found that building the factories required to meet US demand for battery parts and electrolyzers by 2030 will cost $113 billion, with the cost of deploying clean technologies even higher, driving up costs for consumers. Localizing green tech, according to Bloomberg, “means a pricier energy transition just as investment needs to get scaling, fast.”

Another challenge, says Carey, is “making sure that we have the manufacturing capacity to build enough electric vehicles.” Carey points to Ford’s new electric pickup, the F150 Lightning. The automaker received so many reservations, it had to put a temporary halt to them.

Furthermore, many US business owners have already gone through the long, painstaking process of building supply chains in China. “It's really burdensome for small companies….to have to figure out the mechanics of moving supply chains,” says CSIS Senior Fellow Emily Benson.

Benson recently interviewed a small business owner in California who spent two decades forging ties with Chinese business owners: traveling to China, meeting their families, building trust, and over time, developing an understanding of the Chinese market.

“[The business owner] said it's not really enticing for me to have to leave behind my friends that I've made and to forge new contracts in a different foreign market where I'm not familiar with the tariff rates, with the taxation system,” says Benson. “At the very core of trade is a network of humans, and it's really hard to revert knowledge away from one market towards another.”

Transitioning to localized manufacturing will take time, says Murphy, “especially if we have to build some of these industries from scratch and rebuild the pipeline of capable and skilled workers into that.” Murphy adds that bringing in workers with the right capabilities could further lengthen and complicate the process by creating immigration policy issues.

Conclusion

Though recent legislation such as the IRA promises historic investments in the American EV sector, that promise will take many years to be fully realized. This will require sustained effort through different political climates—a challenge that has often proved difficult, especially with regards to climate-related efforts. Successful follow-through on these initiatives will likely depend on how successfully they can be framed not just through an environmental lens but also as a solution to economic and security problems.

Meanwhile, as President Biden makes plans for a 2024 re-election campaign, domestic EV manufacturing will likely remain a pillar of his domestic climate policy, despite the challenges associated with its implementation. Expect Biden to leave his 1967 Corvette in the garage as he hits the campaign trail touting a rapid, ambitious shift to American-made EVs.

Lithium production costs aren’t the only major negative environmental impacts associated with relying on a transition to electric cars to help reach net-zero.

A recent study suggested that up to 34% of microplastics in the ocean come from wearing tires. Not only is this not helped by a move to electric vehicles — it is actively worsened.

Between higher weights and high torque, conventional tires on electric vehicles wear 20% faster than they do on combustion engine cars. A society-wide switch to electric cars would exacerbate this problem.

“What we’re starting to see is this divergence between climate and environmentalism,” Carey said. “You could reach net zero with an ocean entirely full of plastic.”

Work is being done by both tire and car companies to combat this issue, but at the moment it is a very real issue that current American policies will perpetuate.

Salt evaporation ponds are seen on Bristol Dry Lake where Standard Lithium Ltd. is preparing to use Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) technology to capture lithium from brine that is being drawn for evaporation to produce industrial minerals on November 30, 2022 near Amboy, California. | David McNew/Getty Images

Salt evaporation ponds are seen on Bristol Dry Lake where Standard Lithium Ltd. is preparing to use Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) technology to capture lithium from brine that is being drawn for evaporation to produce industrial minerals on November 30, 2022 near Amboy, California. | David McNew/Getty Images

Authors

Audio Team

Rory is a junior majoring in journalism and has a minor in Criminality and Forensics. She is a weather anchor on Annenberg TV News and is a Senior Producer at USC Impact.

Video / Data Teams

Melisa is a political science and journalism student at the University of Southern California. Originally from Mexico City and Baja California, she moved to Los Angeles to pursue a career in journalism. Cabello likes to cover international affairs, politics and human rights, particularly in stories that relate to the Global South and colonialism.

Story and Web Team

Nick Charles is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in journalism and a master’s degree in specialized journalism, with an emphasis in sports and society, at USC. He is also pursuing a minor in comedy performance. He has written stories on COP26, covered NASCAR races and stayed up until 4 a.m. to watch Boris Johnson resign on two separate occasions.

Story and Web Team

Andrew is a journalist and author whose work has appeared in Smithsonian, Alta, Men's Health, Slate, The Daily Beast, and other publications. He studied English and Government at Georgetown University and is a fellow at University of Southern California's Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Story and Web / Data Team

Iliya is a Master’s student in Specialized Journalism at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. He attended University of Maiduguri in northeast Nigeria, where he obtained a Bachelor’s degree in Mass Communication. Iliya worked in Kaduna as a reporter for Radio Nigeria (National Radio); Voice of America (VOA); e-Global; and the UK-based African Farming Magazine, among others. In 2014, he established Africa Media Development Foundation, a media development organization, and in 2015 started Africa Prime News, an online news platform, which reports on issues of interest to Africans.

Video Team

Jinge is pursuing a bachelor's degree in Journalism at the University of Southern California Annenberg. He hopes to become a documentary producer one day through the skills he learns at USC Annenberg. Before transferring to USC, he spent two years at Pasadena City College while working staff as a photographer assistant and live stream specialist. He has a wide range of interests, from golf to football, politics to music.

Story and Web Team

Amina Niasse is a journalism student at the University of Southern California. She has served as an editor at the Daily Trojan and Annenberg Media. Her interests range from economics to film criticism, from long-form documentaries to traditional print.

Video Team

Kylee is pursuing a bachelor's degree in Journalism with a minor in Global Communication at the University of Southern California. She has interned at a local NPR and worked as a multimedia journalist at Annenberg Media covering radio, digital and television stories. She is currently completing an apprenticeship to be an executive producer for Annenberg TV News. She has an assortment of interests that include international affairs reporting and long-form magazine writing on human interest stories.

Special Thanks:

- The Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF)

- Professor Vincent Gonzales, USC

- CSIS iDeas Lab team mentors/staff: Mark Donaldson, Marla Hiller, Shawn Fok, Jaehyun Han, and Sarah Grace

- CSIS AILA staff: Julieze Benjamin, Erin Delany, Nina Tarr, and Donatienne Ruy