Closed Doors,

Open Windows?

Refocusing U.S. Strategy

in the Sahel

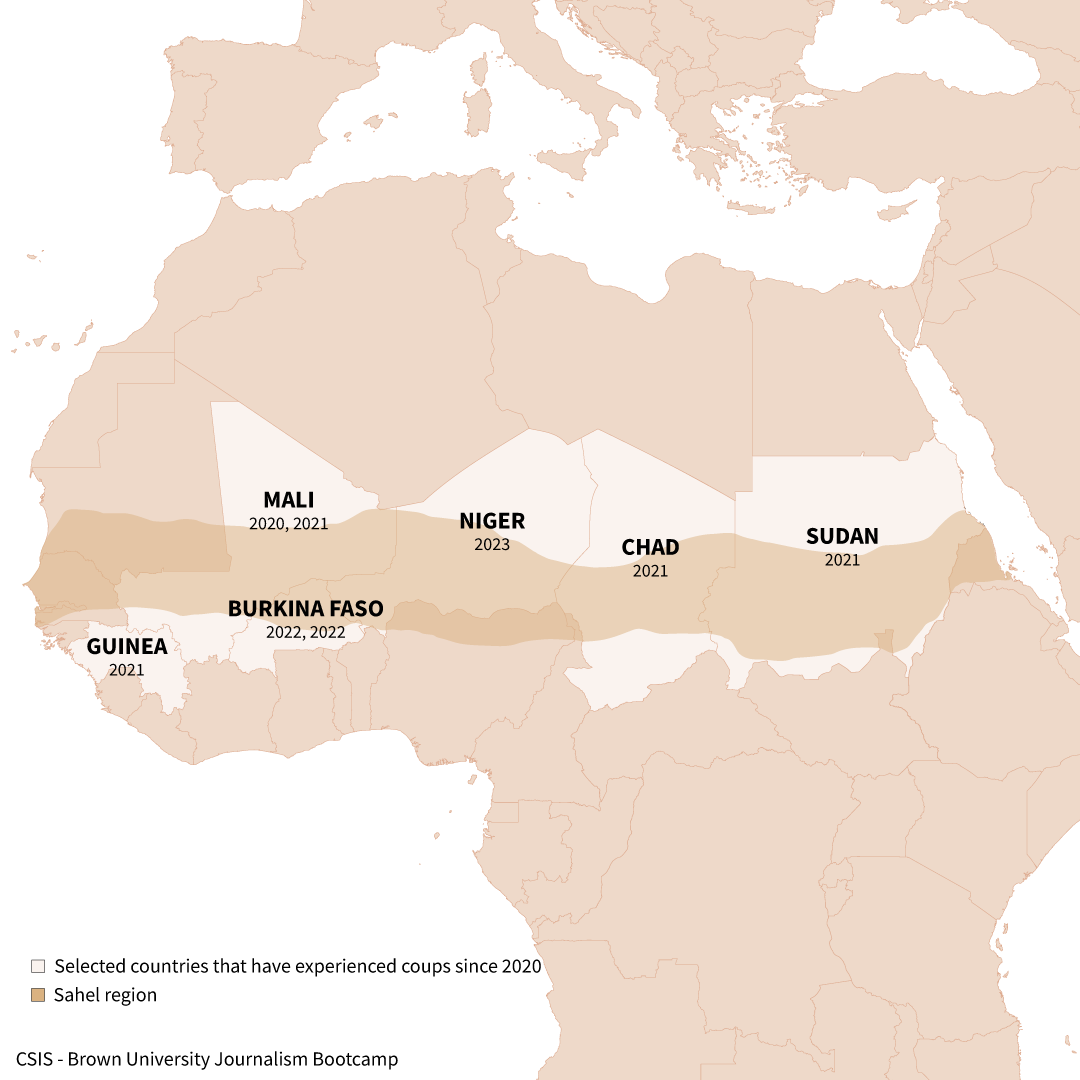

Military Coups in the Sahel: A Disturbing Trend

In July 2023, the Sahel region—home to some of the world’s poorest countries, including Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso—witnessed yet another military coup, this time ousting the democratically elected government of Mohamed Bazoum in Niger.

This is not an isolated event but rather builds on a disquieting trend of political unrest and democratic backsliding, with eight coups unfolding in the Sahel in the span of three years.

Extending over 3,500 miles, this coup belt encompasses a line of six countries—Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, and Sudan. This relentless surge of putsches is now etching the Sahel into the history books as the site of the longest corridor of military rule on Earth.

As the region grapples with these tumultuous events, the Sahel’s political, economic, ecological, and humanitarian challenges appear formidable

Unmet Needs & Challenges

Faced by the Sahel

The underlying motivations for the coups have differed depending on the local, regional, and international contexts, making it challenging to identify specific causes with precision. In some cases, weak civilian governments suffering from insufficient financial and human resources were unable to provide essential public services such as jobs, security, health, and education. This lack of services has disproportionately affected a sprawling youth population in the Sahel. As of 2021, 64.3 percent of the population was under the age of 25 and 44.7 percent was under the age of 15.

Rise of Violent Extremism in the Sahel

In the face of high unemployment and political, economic, and educational marginalization, too many of the region’s young people have been discontent with the inability of their civilian governments to provide stability and security. Limited portions of the populations in different countries were given the opportunity and resources to actively foster and benefit from positive change, which contributed to the perpetuation of an atmosphere of unrest. According to a study by the Council on Foreign Relations, countries with disproportionately large youth populations face higher risks of instability and violence due to factors such as limited opportunities and social tensions. These conditions in the Sahel have fostered an atmosphere of unrest and increased countries’ susceptibility to armed conflict and violent extremism.

"When the government hasn't been able to provide services or support to communities writ large, a lot of times there'll be reaction and that will really help push youth towards alternative means of support."

Over the last 15 years, the Sahel has gone from accounting for one percent of violent extremism in the world to 43 percent in 2023. In a sense, it has become a hotspot for radical Islamist jihadist groups. These range from Boko Haram and the Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) to Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM).

This escalating threat was exacerbated in the early 2010s by the 2011 U.S. intervention in Libya and the 2012 military coup in Mali. Events in Mali led to a jihadist invasion of Northern Mali that spilled over into neighboring West African countries. The situation has been further compounded by the extremely porous borders of the Sahelian countries, the lack of a solid regional structure for military and intelligence cooperation, dysfunctional national armies, and complicated domestic dynamics on the ground.

Anti-French Sentiment as a Catalyst

Amid chronic insecurity and economic instability across the Sahel, an immense surge of anti-French sentiment has acted as a catalyst in propelling military regimes into power.

Out of the six Sahelian countries that had a coup since 2020, five were previously French colonies that had gained independence in the 1960s. Despite this period of decolonization, France remained a powerful presence in the region, establishing an intricate web of influence often characterized as Francafrique.

In 2012, informed by France’s deeply rooted presence in the Sahel, the Malian coup government unsurprisingly sought President François Hollande’s military aid. They requested assistance to counter the takeover of Northern Mali by a coalition of Tuareg rebel and Islamist fighters. Only 12 months later, French troops undertook Operation Serval and successfully repelled the jihadist forces that had taken over about half of the country. Following this operation, only 1,000 French troops were supposed to stay on the ground.

However, in August 2014, after the quick initial success of Operation Serval, France transitioned to Operation Barkhane, the largest external counterterrorism force in the Sahel. However, despite successfully targeting jihadist threats, Operation Barkhane was considered by many to be a failure in successfully ensuring long and lasting peace in Mali. This perceived failure fueled a wave of anti-French sentiment around the region and led to France’s withdrawal from Mali.

France’s decision to pull its embassy and troops from Niger following a December 2023 request from the country’s military junta reflects the increasingly soured relationship between the Sahelian governments and their previous colonial power.

Fuel to the Fire

Though the anti-French sentiment is linked to the Sahel’s long and dark colonial history and the people's frustration with the French military intervention, that sentiment has been amplified by Russia’s growing footprint in the Sahel. Capitalizing on this opportunity to widen its sphere of influence to encompass the Sahel, Russia has actively fomented and supported this anti-western anti-french rhetoric, disseminating misinformation, and filling the vacuum created by the French withdrawal and the relative disengagement or low profile engagement of allies like the United States.

“I think Russia now has new tools at its disposal to spread anti-French, anti-Western sentiment. The use of social media particular to entrench the ideas and themes that their parents or grandparents might have understood when living under French control.”

This strategic exploitation and confrontation with the “Collective West” is shaping the Sahel's political landscape, adding complexity to the region's dynamics and crisis.

Reframing U.S. Interventions:

Lessons Learned from U.S. Partnerships with Niger

The large majority of U.S. interests in the Sahel are centered on maintaining security within the region, including promoting democratic governance and playing a supporting role in great power competition. These goals have resulted in a disproportionate focus on security and counterterrorism programs.

Security Interests in the Sahel

The U.S. partnership with Niger is the deepest example of American involvement in the region. U.S. officials have employed a variety of strategies to address jihadist groups such as Boko Haram and al Qaeda within Niger’s borders.

A U.S. soldier carries his belongings to a waiting truck at a military camp September 21, 2004 on the outskirts of the capital city Niamey, Niger. | Jacob Silberberg/Getty Images

A U.S. soldier carries his belongings to a waiting truck at a military camp September 21, 2004 on the outskirts of the capital city Niamey, Niger. | Jacob Silberberg/Getty Images

Boots on the Ground

By July 2023, the United States deployed 1,100 active military personnel in the country to train local military forces.

Eyes in the Sky

Prior to 2023, the United States spent $30 million annually for Niger Air Base 201 in Agadez — a $110 million air base financed by the U.S. and operated by Niger. Built in 2019, AB 201 is the largest and most expensive U.S. drone base. The U.S. also funded Air Base 101, located in Niamey.

Seeking Democracy

In the earlier part of the decade, the United States expressed significant interest in promoting democracy in the Sahel region, citing the resilience of democratic governments and the ability for democracy to facilitate peaceful solutions. However, the prevalence of coups in Mali and Burkina Faso left the United States with few options for democratic partners.

Niger saw its first democratic transfer of power in April 2021, when President Mohamed Bazoum succeeded Mahamadou Issoufou in a contested election. From the U.S. perspective, Bazoum’s seemingly democratic leadership served as a promising partnership.

Niger's new President Mohamed Bazoum (L) is photographed during his inauguration at the International Conference Center in Niamey on April 2, 2021 | Boureima Hama/AFP via Getty Images

Niger's new President Mohamed Bazoum (L) is photographed during his inauguration at the International Conference Center in Niamey on April 2, 2021 | Boureima Hama/AFP via Getty Images

A man holds a placard reading "Long live Russia" as people demonstrate against French military presence in Niger on September 18, 2022 in Niamey. | Boureima Hama/AFP via Getty Images |

A man holds a placard reading "Long live Russia" as people demonstrate against French military presence in Niger on September 18, 2022 in Niamey. | Boureima Hama/AFP via Getty Images |

Global Struggle, Local Arena

Bazoum’s alignment with the West also enticed U.S. military officials who framed the Sahel as a stage for great power competition. As anti-French sentiment brewed among local stakeholders in the Sahel, departing French troops left a vacuum in the counterterrorism fight against jihadist groups.

As the French withdrew from Mali in 2022, Russia’s Wagner Group began establishing its presence in the Sahel. The Wagner Group sent military advisers to Mali in 2021 and supplied military leaders with arms and security resources in mid-2022. These resources included military trainings and additional personnel—many of whom deployed in major cities and engaged in anti-jihadist campaigns alongside Malian forces. Russia has since phased out the Wagner Group, referring to deployed Russian personnel in the Sahel and Libya as the Africa Corps.

A Democratic "Stronghold" in Niger

In the face of Russian influence, as well as continued U.S. security and counterterrorism efforts, American officials had particular interest in partnering with a seemingly stable, democratic Niger.

“I believe that the United States wanted to demonstrate—with its partnership with Niger—that it wanted to partner with strong democracies,” said Kamissa Camara, former minister of foreign affairs and chief of staff to the president of Mali. “Because Niger . . . was actually one of the last or one of the most stable governments in the region relatively—the United States thought that Niger was going to be a good partner.”

To achieve their various interests, U.S. assistance focused primarily on security policies.

However, these policies failed to address the underlying civilian challenges faced in Niger. In July 2023, Niger’s civilian government was overthrown via a military coup. Leaders removed President Bazoum from office, citing inadequate solutions to national security challenges, deteriorating economic conditions, and poor social governance.

"A Veneer of Stability"

But while several countries declared the events in Niger a military coup immediately following the power grab, the United States hesitated. While the change of power occurred in July, the U.S. government formally declared the takeover in Niger as a military coup in October, months after the original development.

Some experts suggest that the warning signs of an impending coup should have been apparent to U.S. policymakers.

“Niger shouldn’t have come as much of a surprise to the U.S.,” said Franklin Nossiter, a Sahel researcher for the International Crisis Group. “These are fragile regimes in countries . . . where any serious election observer can tell you that free and fair elections are less than free and fair.”

But the United States’ interests in maintaining a democratic stronghold in the Sahel clouded American leaders’ judgement of the fragility in Niger.

“When you want to look past the veneer of stability and democracy, then you will start seeing the cracks,” Camara said. “I don’t know that U.S. officials wanted to see those cracks. I think they were desperate to find a stable and solid partner in the Sahel region, and Niger was a good candidate.”

Even after the veneer of stability fell and cracks in the country’s democracy appeared, the United States was hesitant to declare that a coup transpired in Niger. Why did it take the United States so long to recognize the event as a military coup?

Military coups raise significant economic implications, resulting in barriers to U.S. interests in security and counterterrorism. Section 7008 of the U.S. Department of State’s annual appropriations act, for example, prohibits U.S. departments from providing certain types of security assistance to coup-stricken countries.

Coups also trigger the pursuit of economic sanctions. Following the coup, the Economic Community of West African States enforced a variety of sanctions on Niger, suspending regional financial transactions and freezing Nigerien assets. These sanctions have significantly affected the country’s budget and the lives of its civilians.

Under Section 7008, the United States suspended close to $200 million in humanitarian aid and ceased security cooperations in Niger.

Digging at the Roots: Underlying Drivers of Coup Instability

U.S. assistance to Niger represents a larger trend among coup-stricken countries in the Sahel. While military juntas justify coups by citing security concerns, coups are also symptoms of democratic backsliding and unsustainable governance.

These consistently unmet needs undermine U.S. security interests, as the coups that arise from a lack of effective development programs restrict counterterrorism and security efforts.

A child drawing water from the dry bed of Lake Chad during a drought in Niger. | Thierry Rannou/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

A child drawing water from the dry bed of Lake Chad during a drought in Niger. | Thierry Rannou/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

“Jobs, housing, health care, education […] helps build security in a way that military weapons never will.”

To ensure security, the United States must shift focus and funding to initiatives that address these unmet civilian needs. While the amount of humanitarian aid provided to the Sahel has increased over time, these programs are “band-aid” measures that cannot always contribute toward long-term stability.

“Humanitarian assistance is often very limited in its scope and its focus,” said Noam Unger, director of the Sustainable Development and Resilience Initiative at CSIS. “It’s about saving lives after disaster.”

Future U.S. intervention must dig at the root of the problem—shifting focus away from security assistance and investing in localized strategic development programs.

“For peace and security to hold, you need indigenous solutions. That doesn't come from a foreign country telling the people how they're going to move forward with their government.”

Demilitarizing and Democratizing the American Approach

The U.S. policy approach in the Sahel has long revolved around maintaining a military presence in the region. A reorientation of policy to promote security through prioritizing economic opportunity, education, governance, and localization could prove beneficial in the long term and help maintain peace and prosperity in the Sahel.

Jihadists have taken advantage of the isolated rural communities in the region and have maintained a strong hold over these vulnerable groups. When rethinking what good governance may look like in the Sahel, it is crucial that the region’s governments build the capacity to protect and provide for rural communities, but dialogues must also be opened with rural citizens to identify their crucial needs.

Regional governments should also consider dialogues with militants, should such a move prove to be beneficial for the civilians in regions suffering from violent extremism.

Supporting the youthful Sahelian population, especially in the rural areas, by creating avenues to success through economic development and quality education is vital to curbing jihadist recruitment and strengthening vulnerable democracies.

Agencies such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) are already emphasizing the potential role of aid in reducing conflict. “Improved governance is critical to promoting stability,” said Robert Jenkins of USAID’s Bureau of Conflict Prevention and Stabilization. “It is as important to focus on the delivery of basic services as it is to focus on inclusive, fair, and transparent institutions and political processes. Democracy needs to deliver.”

Localization and Civil Society

By listening to its African partners, the United States can learn that its interaction with the continent demands not only traditional humanitarian aid but also sustained economic investment. By tailoring this form of investment around supporting local businesses, these communities can create sustained demand among the people for proper governance that allows businesses and democracy to thrive.

Experts on the Sahel have highlighted the lack of unbiased localized policy and data. “It’s quite difficult and challenging to find nonpartisan, independent civil society organizations that could provide an unbiased view about the events on the ground,” said Ambassador Kamissa Camara, former chief of staff to the president of Mali before the coup. “That makes it very difficult for this localization aspect to take place.”

Background Music via Storyblocks - Sands of Time by Jon Presstone

Addressing Information Scarcity

A significant shortfall in U.S. assistance is evident in the inadequate support for local journalists in the Sahel, whose insights could greatly enhance the U.S. government’s understanding of the region’s needs.

As a former Department of Defense official noted, “Maybe you find local journalists, maybe you find local pollsters, so that they go find out what the people want, so that you can go to the government to say clearly this is what the people need.”

The recent string of coups in the Sahel are often portrayed as popular movements, but the subpar public opinion polling in the region, especially in rural communities, makes the true popularity of the junta governments unclear, which is one more glaring gap in U.S. knowledge of the region.

“It’s really difficult to know, frankly. I mean, polling all over Africa is a mess,” said Nossiter. “There’s not much of it in West Africa, especially, and in the Sahel, you don’t have this infrastructure like you have in the U.S. of massive public opinion polls everywhere.”

Appeal to the Silenced Majorities

When thinking about how the United States can shift to a localized policy, the demographics of the Sahel are a pivotal factor in achieving stability and development goals. Whether it has been the democratically elected governments of the past or the junta governments installed through the recent coups, younger demographics and women are not heard, leaving the perspectives of large portions of the population without a voice.

U.S. government officials are well aware of the absence of diverse perspectives to inform policy decisions “Oftentimes, the way we work in these countries is we deal with the existing elites. We deal with people who are running the government. If it’s a coup, we deal with the military who’s in charge, plus maybe some of our friends from before,” said Ambassador Rick Barton, the founding assistant secretary of state for the Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations at the U.S. Department of State. “The people who tend to get left out of these conversations are women and young people because they have not been in the ruling elites.”

The security of women and young people is a crucial piece missing in the puzzle to securing the Sahel. U.S. policy needs to focus on lifting up these vulnerable groups to ensure their needs are heard, thereby enabling the entire region to flourish. Empowering them is not just a moral imperative but a strategic necessity to foster peace, stability, and prosperity throughout the Sahel.

Different Organizations with Different Missions

It is important to note that the U.S. government is not a monolith. The Department of Defense’s mission tends to focus on a strategy of military partnership and combating militants in the Sahel, overlooking the needs of civilians. However, some organizations seek to provide humanitarian and economic relief, such as USAID and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC).

The MCC is a bilateral and independent U.S. government foreign aid agency that works to reduce poverty through economic growth. The MCC is committed to just and democratic governance and aims to invest in the populations of the poorest nations on earth. In the Sahel, the MCC allotted $442.6 million to the Niger Compact. Unfortunately, on September 13, 2023, the MCC’s board of directors voted to suspend the organization’s partnership with Niger due to the military coup, putting an end to a program that had the potential to benefit approximately 3.9 million people. The suspension represents a significant setback for positive change, depriving millions of Nigeriens of vital economic and infrastructure developments that could have enhanced their quality of life and accelerated the country’s journey toward sustainable growth and stability.

Cameroonian soldiers take part in a counter-terrorism training session with United States Special Forces in Ghana, on March 11, 2023. | Nipah Dennis / AFP

Cameroonian soldiers take part in a counter-terrorism training session with United States Special Forces in Ghana, on March 11, 2023. | Nipah Dennis / AFP

Conclusion

The epidemic of coups in the Sahel has attracted Western attention for a variety of reasons. As jihadist groups continue to create violence and instability, France withdraws from the region, and Russian forces enter the equation, the United States has adopted a largely military-first approach.

While security programs have been the primary form of U.S. assistance, these efforts have been unable to get at the underlying roots of ongoing instability and military coups. Although humanitarian aid can temporarily remedy the hardships facing civilians, new initiatives must be adopted and better supported for long-term development.

When supporting these initiatives, the United States must think from the bottom up, rather than from the top down. Local non-governmental organizations, economic development groups, and other indigenous stakeholders understand the needs of Sahelian communities in the greatest detail. The United States and other global powers must highlight their voices in the path toward regional stability and prosperity.

Authors

Special Thanks:

Story: Mark Donaldson & Claire Smrt

Video: Michael Kohler

Audio: Marla Hiller

Data: Jaehyun Han

Editorial: Sarah Grace