CHARTING THE PATH TO TRUST

What the United States Can Offer the

Pacific Islands in Their Fight to Survive

the Impacts of Climate Change

November 22nd, 2024

The Pacific Islands face existential threats from climate change.

But they can’t overcome these threats without the support of other countries.

The United States has a vested interest and historic responsibilities in the region, but it faces stiff competition for partnership and influence.

As economic, societal, and environmental impacts mount, how can the United States help the Pacific Islands navigate these perilous tides?

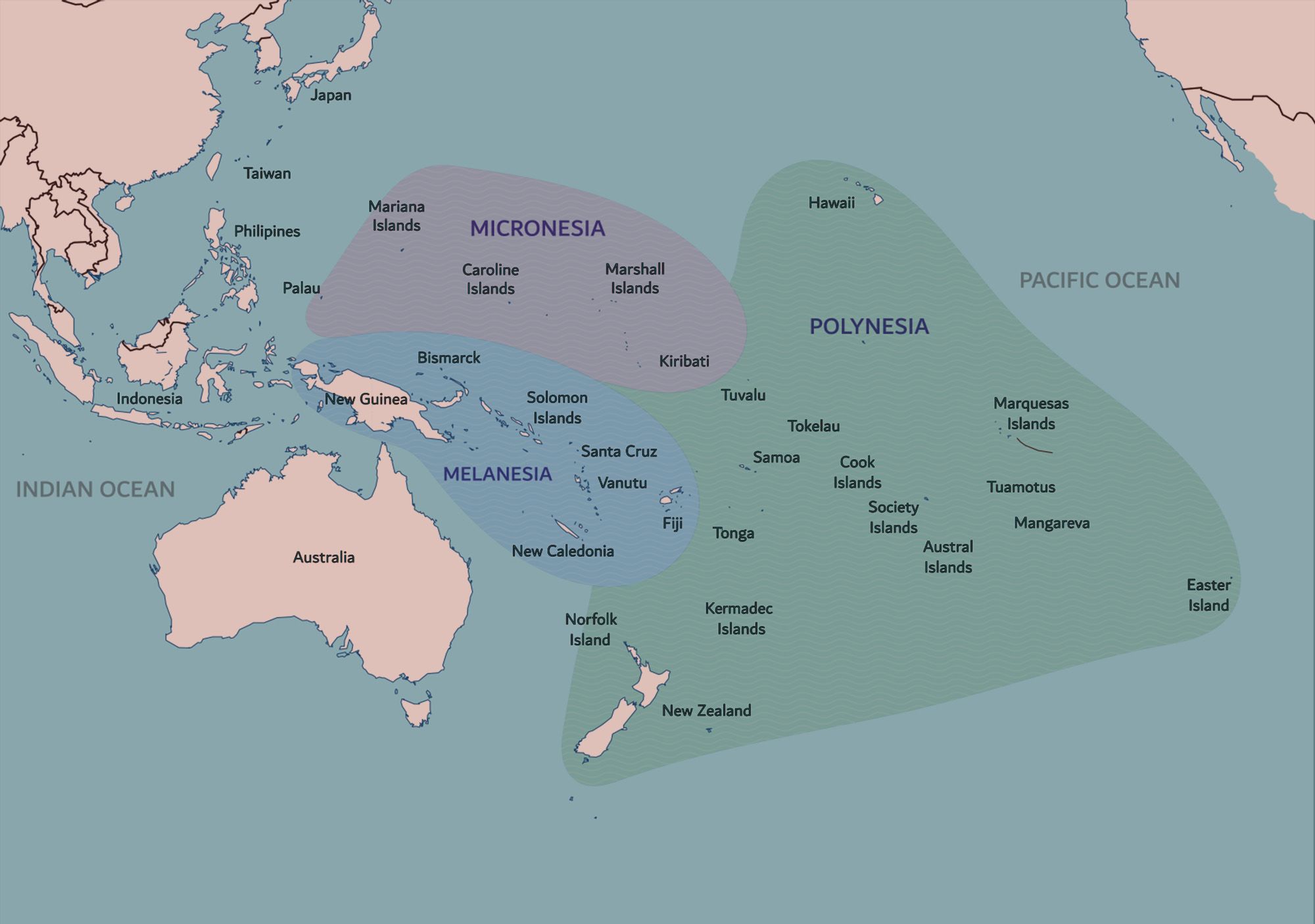

The Pacific Islands cover roughly 15 percent of the Earth’s surface and comprise 14 sovereign nations divided into three subregions: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia.

The region’s vastness necessitates an in-depth understanding of its people, cultures, and impact on the rest of the world to develop effective policy and provide aid.

In particular, it’s critical to understand the existential threat that climate change poses to the region.

Rising sea levels threaten to overtake some islands completely, many of which range from three to seven feet in maximum elevation. The rising levels will continue to result in forced migration, which is already occurring in Kiribati, an island country in Micronesia.

There has also been an increase in extreme weather events and changing climate patterns, which has resulted in droughts and flooding on the islands.

“We talk about human security, all elements of human life . . . all elements of things that make life possible on these islands, that they are becoming growingly insecure,” said Dr. Satyendra Prasad, former Fiji ambassador to the United States and permanent Fiji representative to the United Nations.

In addition, the region is home to more than 75 percent of all known coral species. These coral reefs are usually filled with vibrant color and marine biodiversity, but marine heat waves have bleached them. This has caused marine life that rely on the reefs to move away from the area, further damaging the ecosystem.

These three regions are filled with rich cultures and biodiversity that their people are trying to preserve.

A Strategic Ally to Fight Climate Change

The Pacific Islands also hold significant strategic importance for several world powers, including the United States. As a result, the United States is striving to maintain and grow its Pacific Island allies.

Marines salute after hoisting the national flag at the U.S. embassy in Honiara, Solomon Islands, on February 2, 2023.

Marines salute after hoisting the national flag at the U.S. embassy in Honiara, Solomon Islands, on February 2, 2023.

“If there were to be a conflict tomorrow, influence and presence and the ability to have those relationships in the Pacific would be absolutely critical.”

Kathryn Paik, senior fellow with the Australia Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and former director for Southeast Asia and the Pacific on the White House National Security Council.

The region’s geopolitical significance has partly contributed to the United States’ increased presence.

However, the United States must consider the islands’ needs to most effectively engage with the region and listen directly to regional voices. Chief among these needs is assistance with addressing the impacts of climate change.

Pacific Islands Under Threat:

Climate Change

The impacts of climate change—particularly increasing ocean temperatures, a scarcity of food sources, and limited access to clean water—are felt acutely in the Pacific Islands region.

The islands are suffering from consequences they largely did not create.

The United States contributes 5.06 billion metric tons of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, accounting for approximately 13.5 percent of total global CO2 emissions. In comparison, China emits around 27 percent of the world’s CO2 emissions.

Rising sea levels and increasingly frequent intense storms continue to destroy infrastructure and inhibit trade, leaving some island residents without homes and livelihoods.

In addition, the warming of the waters is not only creating more destructive and frequent natural disasters but is also causing tuna, a primary source of food and key export, to move toward cooler waters.

Additionally, the impacts of climate change have left some Pacific Islanders with drastic shortages of clean water. Some countries in the region rely on rainwater, which has led to cancer and reduced birth weights.

Droughts, flooding, and tropical storms have reduced access to clean water and sanitation. The strain on the region’s small amount of water will only increase as the Pacific Islands’ population grows.

Nations in Melanesia have seen notable population growth. For example, Papua New Guinea has seen over 2 percent growth, and the Solomon Islands has experienced 1.65 percent growth in population in the last few years.

This growing population has strained natural resources and economic opportunities across the Pacific Islands, where 75 percent of the population is made up of young people.

Pacific Islands Under Threat:

Economic Opportunities

Research from the World Bank has highlighted several economic issues in the Pacific Islands that could be alleviated through outside assistance.

One such issue is illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. This affects not only economic opportunities but also sovereign rights and security in the islands.

Fishing

Tuna exports from the Pacific Islands account for 30 percent of the global tuna market, totaling about 1.4 million metric tons of tuna.

For some Pacific Island nations and territories, revenue from tuna exports makes up 84 percent of all government revenue, and the industry creates about 25,000 jobs in the region, which comprises around 2.3 million people.

In addition, fish is a substantial part of the Pacific Islands diet. People in the region are two to four times more likely to consume fish than in other parts of the world.

According to the World Bank, the Pacific Islands lose $739.86 million annually to IUU fishing.

For example, on March 2, 2024, six Chinese fishing boats were found to be violating Vanuatu’s fisheries laws.

IUU fishing has clear negative economic impacts on the islands, especially in conjunction with fish leaving the area due to the impacts of climate change. This decreasing availability of fish has damaged the islands’ ability to feed their own people.

“When that [ability to feed people] declines, you rid the capacity of that nation state to acquire food. Most people in the Pacific Islands occasionally will fish for their own food.”

Dr. Alan Tidwell, professor of the practice and director of the Center for Australian, New Zealand and Pacific Studies at Georgetown University's Walsh School of Foreign Service.

Given that the islands have extensive knowledge of their own lands, the United States could help mitigate IUU fishing by providing financial aid, as well as offering boats and other resources to support monitoring efforts.

The U.S. Coast Guard has already begun to help with this issue in other countries, such as the Bahamas.

For example, in the maritime agreement the U.S. Coast Guard has with the Bahamas, Bahamian law enforcement officials are able to board U.S. vessels and aircraft and grant those vessels and aircraft authorities to assist in enforcing Bahamian laws.

Pacific Islands Under Threat:

Impacts to Infrastructure

Another significant issue impacting economic opportunities in the region is damage to infrastructure, which is mainly caused by climate change–related events such as devastating natural disasters.

With the waters rising, whole roads are disappearing.

Without access to roads, it’s challenging for Pacific Islanders to leave their homes, visit other communities, and trade.

“...these small economies, not one of them can manage the kind of infrastructure costs that climate change holds out for them.”

Dr. Alan Tidwell, professor of the practice and director of the Center for Australian, New Zealand and Pacific Studies at Georgetown University Walsh School of Foreign Service.

Background Music via MotionArray

“You start from a lower base each time we recover. The quality of health care declines, the quality of roads declines, and airports shut down,” Ambassador Prasad said. “Societies and these small states are becoming growingly unstable.”

Climate change impacts and economic opportunities are some of the issues the islands have identified as areas that would benefit from foreign assistance.

The United States has already begun to address these issues and generally increase its engagement with Pacific Island nations, but it needs to continue to recognize its historical relationship with the region in order to overcome other barriers.

U.S. Engagement

Over Time

Historic U.S. Engagement

The United States has a tumultuous history with the Pacific Islands, which complicates its ongoing efforts to engage with the region.

During World War II, the United States and Japan competed for influence in the Pacific Islands.

The United States, along with other colonial powers such as France, maintained territories and possessions during this time, some of which are still in place today.

After the war, the United States began atomic bomb testing in the Bikini and Enewetak Atolls in the Marshall Islands.

This nuclear testing continues to impact the relationship the United States has with the Pacific Islands.

A satellite image of the nuclear test craters on Enewetak Atoll, which remain to this day.

A satellite image of the nuclear test craters on Enewetak Atoll, which remain to this day.

“We have a unique relationship with [the Marshall Islands]. At the same time, conversations around nuclear testing continue to permeate most of that conversation on a government-to-government and people-to-people level,” said Paik.

In the latter half of the 1900s, the Pacific Islands declared independence from their colonial administrators. From 1962 to the present day, 15 Pacific Islands have become their own sovereign nations.

Because of their size, the Pacific Island nations believed it was important to appear unified on the international stage. In 1971, they created the Pacific Islands Forum.

More recently, the Pacific Islands have been courted by China for geopolitical reasons. In 2019, both Kiribati and the Solomon Islands shifted their diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China, a sign of China’s growing influence in the region.

This crystallized with the signing of a security agreement between the Solomon Islands and China in April 2022, which alarmed Western nations as a potential precursor to China’s future military presence in the region.

As a response, the United States and its allies have sought to increase their attempts to combat this influence through engagement of their own.

Recent U.S. Engagement

The United States’ recent regional engagement has taken several forms, including soft power approaches such as inviting leaders to the White House and implementing specific programs.

President Trump met with presidents of members of the Freely Associated States in 2019, which was the first time a U.S. president had invited the leaders of the Republic of Palau, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Federated States of Micronesia to the White House.

In 2022, President Biden hosted the first-ever United States-Pacific Island Country Summit in Washington, D.C. He later hosted the Pacific Islands Forum members again the following year.

These meetings demonstrate the United States’ increased engagement in the region, as many Pacific Island leaders had not previously been invited to the White House.

Another example of recent U.S. engagement in the Pacific is U.S. support for specific development projects.

In June of 2023, the United States, along with Japan and Australia, began funding an underwater cable in the Pacific to help bring internet access to Kosrae in the Federated States of Micronesia, as well as to Nauru and Kiribati (especially Tarawa, the capital of Kiribati).

This cable helped connect the three countries to the existing cable in Pohnpei, Micronesia, facilitating high-speed, high-quality, and secure communications for more than 100,000 residents, businesses, and governments.

People stand in an internet cafe in the village of Ambo located on South Tarawa, Kiribati.

People stand in an internet cafe in the village of Ambo located on South Tarawa, Kiribati.

Projects like these are some of the most effective ways the United States can engage with the region.

“The U.S. has been most effective, frankly, when we have done two things,” Paik said. “One, listened to the Pacific and their needs and worked in conjunction with the Pacific. And also worked with our partners and allies – we have done many bilateral initiatives ourselves, but our most successful ones have been in partnership with others.”

Challenges and Opportunities for Future U.S. Engagement

The United States faces several barriers to its engagement in the Pacific, including its failure to uphold climate change promises, limited diplomatic engagement, and competition with China.

One obstacle informing the United States’ struggle to engage diplomatically in the region is the limited administrative, financial and infrastructural capacity of the region’s small island nations.

For example, several Pacific countries don’t yet have U.S. embassies due to the size of the islands and the infrastructure needs surrounding potential U.S. personnel.

“This really limits and hampers our ability to engage with Pacific Islanders on the ground and to engage with local governments and build those critical relationships moving forward,” Paik said.

Paik explained some of the logistical barriers the United States faces when creating embassies in the Pacific Islands: “If they have families, there needs to be schools. There are certain medical requirements . . . [h]owever . . . there are waivers for certain requirements.”

More recently, the United States opened embassies in Tonga, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu, but it still remains behind China both in terms of the number of embassies in the region and the number of people on the ground to staff them.

The lack of U.S. diplomatic presence in the region also highlights the competition the United States faces for influence, primarily with China.

Not only has China been able to expand its diplomatic presence more effectively in the region, but it’s also contributed many loans for projects related to climate infrastructure.

Although these loans often come with multiple stipulations and leave the islands in debt to China, some funded projects have been successful.

Although these loans often come with multiple stipulations and leave the islands in debt to China, some funded projects have been successful.

“The quality of the infrastructure also sometimes is not aimed at being purely climate resistant. It is more to be built quickly and flashy. That said, there has also been good climate resilient work done by China,” explained Paik.

China’s expanding presence in the region is a top concern for the United States, and meeting the region’s infrastructure needs can help combat creeping authoritarian influence.

“If the international rules and norms of commerce were to become eroded, as China has attempted to do in many other parts of the world, that could significantly affect the way the U.S is able to maintain its economic security in the region,” said Paik.

Optimizing Support

To improve its engagement in the region, the United States should adapt its financing strategy and use its voice on the global stage to encourage assistance for the islands in international organizations.

The U.S. government can only donate so much to combat the ongoing climate crisis; federal resources need to be supplemented by private sponsors.

In particular, the U.S. government can encourage more public-private partnerships to address the islands’ specific needs, such as building infrastructure.

“We tend to like to build the deep architecture of infrastructure, particularly in the technological realm, but we’re not really in the business of building stadiums, building roads, building ports or airports. And yet so much of that is what we hear from our friends in the Pacific,” said Dr. Charles Edel, senior advisor and inaugural Australia chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Children watch the sun set over a construction site where China is building a $50 million stadium for the Solomon Islands ahead of the Pacific Games next year.

Children watch the sun set over a construction site where China is building a $50 million stadium for the Solomon Islands ahead of the Pacific Games next year.

But financial assistance is only part of the battle.

Because their bureaucracies are small compared to those of many other countries, some Pacific Island nations believe there should be different processes to access money depending on the scale of the operations of the nation in question.

“Right now, small island states’ access to global funds, such as from [the] World Bank and IMAP, is more or less exactly the same as it is for Indonesia or India. We have to go through the same processes, the same rigmarole, the same layers of bureaucracy to be able to access funds from these global institutions,” said former ambassador Prasad.

The United States could use its global voice to help influence future processes in institutions such as the World Bank and advocate for changing the limitations these small islands face.

The Path Forward

From November 11–22 of this year, the international community will meet at the 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) to discuss the global climate outlook. This forum will give the world delegates a chance to discuss exactly how to fund the changes needed to slow or completely stop the effects of climate change.

Ahead of the forum, Pacific Island leaders were vocal about the need for immediate global action on achieving climate outcomes.

“Our survival cannot be compromised. Climate change is the single greatest threat to the livelihoods and security of the Pacific,” said Pacific Islands Forum chair and prime minister of Tonga, Hu’akavameiliku, a day before the forum. He noted that the Pacific Islands as a region “is fully committed to ensure COP29 delivers on outcomes that benefit not just our people, but mankind as a whole.”

Other island nations are less optimistic. In August, Papua New Guinea’s prime minister James Marape made the decision to withdraw from attending COP29 to protest the global lack of climate action.

“We will no longer tolerate empty promises and inaction, while our people suffer the devastating consequences of climate change,” Papua New Guinea’s foreign minister Justin Tkatchenko said one week before the summit.

In order to win back the trust and secure the future of not only the Pacific Islands but also the global community in the long term, attending nations must deliver stronger outcomes during COP29 than they have in the past.

The New Collective Quantified Goal, established in 2009 as part of the Paris Climate Agreement, aims to fund countries’ post-2025 climate needs. However, the goal continues to face resistance within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

The international community must keep an eye on this new and clear collective goal. This will contribute to transparency and ensure that the countries that need aid most will get it. This is vital to the survival of the Pacific Islands.

As the threat of the climate crisis continues to loom over the Pacific Islands, accountability and transparency from the United States are critical to navigating the region’s future.

Authors

Special Thanks:

Story: Marla Hiller & Gina Kim

Video: Shawn Fok

Audio: Cera Baker

Data: Jaehyun Han

Editorial: Sarah B. Grace