CSIS Journalism Bootcamp:

Student Perspectives

Challenging Thailand's Cycle of Corruption & Human Trafficking

The Thai government has recently implemented initiatives to prevent and suppress human trafficking, but there is still much work to be done. What role does corruption in Thailand’s institutions play in undermining these efforts? What steps can be taken to combat this corruption and achieve goals that will reduce human trafficking?

Story & design by: Kenna McNally, Arien Roman Rojas, and Bella Waters

Video by: Caleb Beasley, Allison Muzzy, and Aminah Syed

Data research & visualizations by: Abbie Clements and Cuyler Dunn

Podcast by: Taylor Doyle and Grace Hills

May 1, 2025

Wang Xing, a small-time Chinese actor, thought he had landed a role in a Thai production. He saw a casting on WeChat, sent an audition tape in, and was told he had gotten the part.

On Jan. 3, 2025, he traveled to Bangkok to start filming. However, when he got into the car provided by the supposed entertainment company in Thailand, he was not taken to a hotel or studio. Instead, he was driven to Myanmar, where he was forced to work in a scam call center on the border.

Five days later, Xing was rescued. However, countless other trafficked individuals remain trapped in that call center. Since Xing’s rescue, the Thai government has renewed efforts to crackdown on these illegal operations.

According to CSIS, people from over 100 countries were trafficked into Southeast Asia’s scam centers in 2024. These scam centers earn $43.8 billion annually, which funds various criminal activities.

Scam centers are just one form of human trafficking in the region: other forms of labor trafficking and sex trafficking are prevalent and increasing. This issue extends far beyond Southeast Asia however.

Countries like Thailand have funded initiatives to combat these issues, but millions of trafficked individuals are still in jeopardy.

Government Efforts Against Trafficking

Thailand is known for its high rates of human trafficking through sexual exploitation, the fishing industry, scam centers, and other methods. In recent years, the Thai government has increased its efforts to curb trafficking.

In October 2024, Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra announced the Measures for Prevention and Suppression of Trafficking in Persons in Business Establishments, Factories, and Vehicles, which requires business owners to provide employees with information on how to prevent and end human trafficking. These trainings must be provided to employees at least once per year. It also requires workers to be allowed to contact external individuals and file cases alleging human trafficking or forced labor.

The Thai government allocated $3.2 million in 2023 and $12.9 million in 2022 to its prevention and suppression of trafficking budget. The National Anti-Trafficking in Persons Committee conducts anti-trafficking awareness and prevention campaigns and coordinates with other agencies, including the Ministry of Tourism and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

After the U.S. Department of State’s 2024 Trafficking in Persons Report was released, keeping Thailand at a Tier 2 rating for the third consecutive year, the Thai government released a statement commending its efforts and citing anti-trafficking as having “long been one of Thailand’s top national agendas.”

The 2024 statement recognized how many of these years-old laws were not as immediately effective as many would have hoped, instead having required the Thai government to have “constantly strengthened laws and regulations and increased operational efficiency.”

Despite all of these efforts, Thailand has made limited progress as it continues to not meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking. Inconsistent interviewing techniques, lack of effort in identifying and protecting victims, and a multilevel system of corruption that impacts law enforcement, immigration, and the judiciary are all contributors to this lack of success.

Corruption impedes efforts to identify and support survivors, bring traffickers to justice, and break illicit syndicates. Researchers who studied the problem on behalf of the Thai government concluded that corruption “not only facilitates but causes and perpetuates trafficking activities.” Exploring and addressing corruption in the institutions combating human trafficking in Thailand will therefore be an essential part of addressing the trafficking issue.

Police and military personnel conduct raids in Thailand in a campaign against human trafficking and corruption. | Photo by Madaree Tohlala/AFP via Getty Images

Police and military personnel conduct raids in Thailand in a campaign against human trafficking and corruption. | Photo by Madaree Tohlala/AFP via Getty Images

Systemic Corruption in

Law Enforcement

According to the 2021 Global Corruption Barometer, a majority of Thai citizens have low trust in the police. While precisely tracking the causes and effects of corruption can be challenging, there are several key factors that likely contribute to the problem within Thailand’s police forces.

Lack of Funding

The willingness of law enforcement to participate in corruption is due to a combination of low pay and a normalization of bribery. “Low pay has long been cited as the main contributor to widespread corruption in the force,” a story by the Bangkok Post said.

However, taking a bribe is not always an officer’s first choice. The Transparency International Anti-Corruption Helpdesk states that accepting gifts is usually the first step in working up to accepting things of higher value in exchange for turning a blind eye to corrupt practices from labor traffickers. Officers who are already struggling to make ends meet, who live within this system that heavily normalizes bribery in general, fall into this corrupt behavior out of perceived necessity.

“It’s important that people in these roles are paid a living wage and thus don’t find it necessary to take a bribe in order to make sure that they can put food on the table,” Andrew Friedman, senior fellow at CSIS’s Human Rights Initiative, said. “But it’s also important to ensure that there’s a societal or a political and legal understanding that these are crimes.”

Police inspect a foreigner's passport in Bangkok's Patpong district during a police operation called "X-Ray Outlaw Foreigner." | Rome Gacad/AFP via Getty Images

Police inspect a foreigner's passport in Bangkok's Patpong district during a police operation called "X-Ray Outlaw Foreigner." | Rome Gacad/AFP via Getty Images

Normalization of Bribery

According to data found by the Global Corruption Barometer, almost 50 percent of people in Thailand have admitted to bribing the police. In a story by the Bangkok Post, a man from Myanmar admitted to having bribed immigration police and local police to smuggle workers into Thailand.

As bribery becomes expected by the public, it can also become normalized within police forces. According to Transparency International, one possibility for the continued existence of corrupt behavior in law enforcement is the fact that loyalty is given priority when coworkers engage in corrupt behavior.

“If an individual police officer believes that every police officer takes a bribe, they’re going to be more okay taking a bribe than if they think they’re the only one,” Friedman said.

High-profile bribery cases have reached the highest levels of police leadership, contributing to the perception of widespread corruption. In 2018, Thai National Police Chief Pol Gen Somyot Poompanmoung, who had publicly championed the country’s anti-trafficking efforts, admitted to receiving a $8.8 million loan from the owner of the Victoria’s Secret massage parlor, which has been investigated as a site of human trafficking, prostitution, and money laundering.

Potential Solutions

The solution to funding may appear obvious: Raise the police’s salary so they don’t need to take illicit compensation to get by. However, research has demonstrated that raising policemen’s salaries without targeting the culture of bribery hasn’t been successful.

“Just making more money is not going to reduce the probability of corruption,” Brooke Stearns Lawson, an anti-corruption expert, said.

Africa that making law enforcement feel their work is valued can reduce willingness to accept bribes.

“When you accompany it with other factors that allow them to be respected in their profession, it can mitigate that,” Stearns Lawson said. “It can be something as simple as quality uniforms. It can be as simple as badges.”

Still, dismantling the system that leads to average citizens and law enforcement believing that bribery will go unpunished is essential. Ensuring that the risks of participating in corruption outweigh the benefits of illicit income is a necessity.

“The most surefire way to ensure that actors don’t engage in corruption is ensuring that they’re held accountable when they are,” Friedman said.

Royal Thai Maritime Police officers patrol fishing boats seized for illegal fishing at Songkhla port in Songkhla, Thailand. | Dario Pignatelli/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Royal Thai Maritime Police officers patrol fishing boats seized for illegal fishing at Songkhla port in Songkhla, Thailand. | Dario Pignatelli/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Zooming in on Immigration

Immigration enforcement has the potential to both disrupt and enable human trafficking. Immigration officials, with the right training, can identify victims of trafficking and provide the necessary services to escape.

Many victims of trafficking never cross international borders. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes found that 76.6 percent of detected victims of trafficking in the East Asia and Pacific region in 2023 were being trafficked within the country where they have citizenship. However, transnational networks often rely on corrupt immigration officials to move trafficked people across borders without legal documentation.

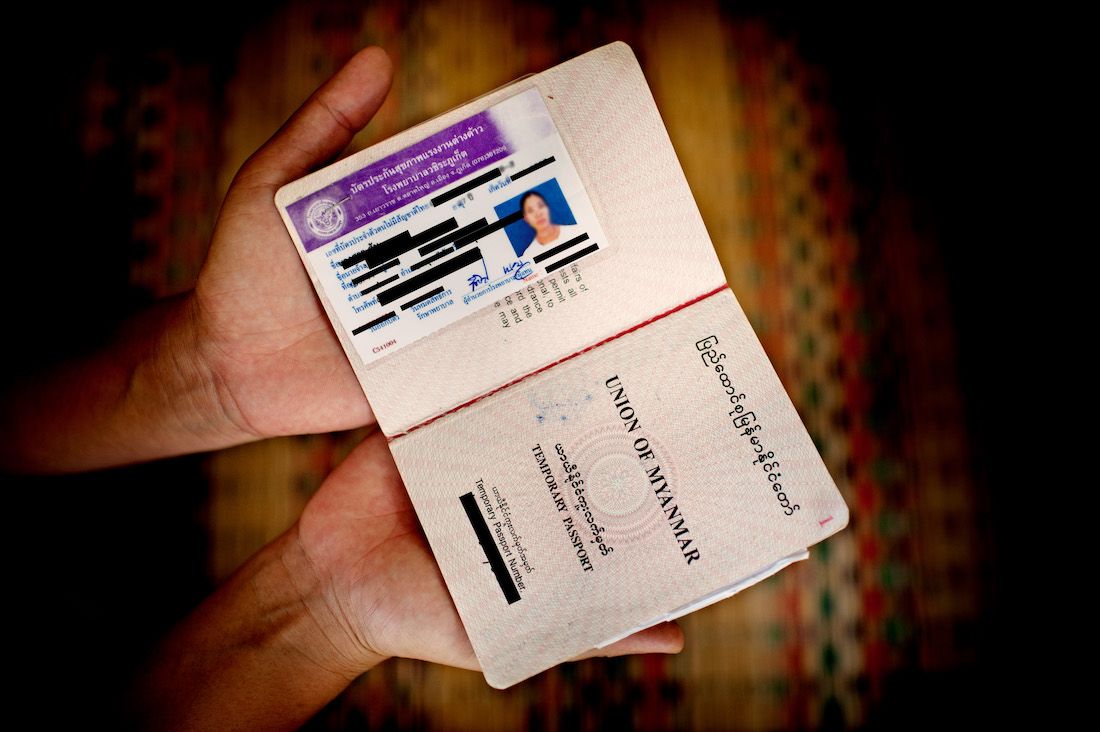

A migrant worker from Myanmar shows her work visa inside her passport. | Photo by Jonas Gratzer/LightRocket via Getty Images.

A migrant worker from Myanmar shows her work visa inside her passport. | Photo by Jonas Gratzer/LightRocket via Getty Images.

Attempted Crackdowns

Thailand requires that foreign citizens have a valid passport. Some travelers must also have a Thai visa, while Southeast Asian countries only need a Thai visa—in addition to their passport—to stay longer than 30 days.

Smugglers have frequently sidestepped these visa requirements by paying bribes to immigration officers. “Each migrant has to pay immigration police 3,200 baht each to obtain a border pass which allows them to stay in Thailand for seven days,” said a man only identified as Win in an interview with the Bangkok Post in December 2024. “After the seven days, I bring the migrants’ border passes to the authorities who rubber stamp them to show that the alien workers have returned to Myanmar despite the fact that they are still in Thailand.”

Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra ordered a crackdown on immigration enforcement in January 2025, increasing the frequency from the standard three checks per year. However, these efforts to tighten immigration controls can sometimes negatively impact victims of trafficking.

If non-Thai citizens are caught in the country illegally, they are often imprisoned, even if they are being trafficked. This may serve to deter victims of trafficking from cooperating with law enforcement, as victims know they will likely be further victimized by the immigration system. According to a 2024 Department of State report, “The government’s requirements . . . deterred many potential victims from reporting their exploitation or agreeing to participate as witnesses.”

With the increasing prevalence of scam centers on the Thai-Myanmar border, trafficking victims often find themselves in an immigration grey area. Many of these centers exist in special economic zones with varying levels of legal protection for employees.

“Border zones in Thailand and throughout mainland Southeast Asia . . . The law is the weakest there,” said Japhet Quitzon, associate fellow with the Southeast Asia Program at CSIS. “It’s quite easy to find a border agent who may be sympathetic to you, who you’ve worked with in the past, who you know you can pay off to let people in and out.”

As trafficking increases in areas where enforcement of immigration laws is at its most inconsistent, it will be difficult for the Thai government to combat bribery and corruption among immigration authorities. But doing so, while avoiding punitive measures against the victims of trafficking themselves, will be essential to disrupting the transnational networks trafficking people across the border.

Old border entrance gate between Thailand and Myanmar. | Eurostar1977 via Adobe Stock

Old border entrance gate between Thailand and Myanmar. | Eurostar1977 via Adobe Stock

A Thai policeman inspecting documents of a Laotian driver at a road checkpoint in Muang, Nakhon Phanom province. | Photo by Aidan Jones/AFP via Getty Images

A Thai policeman inspecting documents of a Laotian driver at a road checkpoint in Muang, Nakhon Phanom province. | Photo by Aidan Jones/AFP via Getty Images

Breaking the Cycle

Corruption and trafficking exacerbate one another, so trafficking cannot be addressed without addressing corruption. Thailand has made efforts to combat corruption in its government, like establishing anti-corruption commissions. However, more work still needs to be done to make these efforts more effective.

Increased safety initiatives, more staff, more prosecuting power, and more legal independence can all bolster Thailand’s anti-corruption initiatives. Beyond addressing corruption, more economic incentives for vulnerable populations in Thailand can help prevent people from entering, or reentering, trafficking at all.

Anti-Corruption Initiatives

Thailand has had a National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) since 1999. This commission holds the power to prosecute high-ranking Thai officials who engage in corruption.

According to the 2017 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, the NACC has the responsibility to “conduct an inquiry and decide whether a government official is unusually wealthy, has committed an offense of corruption, or malfeasance in public office or malfeasance in judicial office.”

Last year, the NACC found four former executives of an oil and gas company guilty of corruption, collusion, and bribery.

Another government agency tasked with fighting corruption in Thailand is the Public Sector Anti-Corruption Commission (PACC), which makes recommendations about corruption among lower-level officials. According to its website, the PACC was created in 2008 after the NACC was overloaded with cases.

Thailand is actively trying to prevent corruption within its government through these various bodies. According to the NACC, Thailand wants to enhance its “reputation as a nation striving towards zero corruption.”

Produced by Taylor Doyle, Grace Hills, and Marla Hiller (iDeas Lab).

Music: Surviving and How Dare by Tom Fox.

Thai policemen stand guard at a court in Bangkok | Photo by Lillian Suwanrumpha/AFP via Getty Images

Thai policemen stand guard at a court in Bangkok | Photo by Lillian Suwanrumpha/AFP via Getty Images

Shortcomings in the System

Thailand is making efforts to combat corruption, but corrupt activity still goes unprosecuted. According to a news release, the NACC identified 1,553 cases of corruption between 2022 and 2024. However, only 339 cases have been resolved, and only 60 were confirmed as corrupt. Many “ongoing cases” are years old, too, with no path to conviction, according to a 2021 study.

One individual interviewed in a study never saw their case pursued: “I made a complaint against the police in 2009. At first, I got a few phone calls from the PACC staff asking me about the case but after a year, no one has ever contacted me again, no investigation whatsoever, I totally felt let down.”

Safety concerns also prevent the NACC from operating effectively. According to the Bangkok Post, officials in the NACC were offered bulletproof vehicles during work.

“People investigating corruption usually face enormous risks,” Carolina Jiménez Sandoval, president of the Washington Office on Latin America, said.

Police stand guard at the National Anti-Corruption Commission office outside of Bangkok | Photo by Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

Police stand guard at the National Anti-Corruption Commission office outside of Bangkok | Photo by Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

According to the 2021 study by Dhiyathad Prateeppornnarong, the PACC is also at risk of politicization, which undermines effectiveness: “Political patronage, as a long-established feature in Thai society, is highlighted as one of the issues giving way to politicization of the system.”

The same study also cited an inadequate number of qualified staff at the provincial offices of the PACC and the absence of meaningful public participation in the process as obstacles to fulfilling its mission.

Bridging the Gaps

According to Jiménez Sandoval, “there is no way to fight corruption without a free and independent judicial branch of government.” Judicial independence from political influence and other non-political actors within the courts, like members of organized crime, can help the courts fight corruption in other sectors of the government.

According to Prateeppornnarong’s study, numerous officers within the PACC believe that increased prosecuting power within the institution could discourage government officials from participating in corruption. The PACC cannot currently prosecute accused actors itself but can only make recommendations for prosecution to other bodies, like public prosecutors and the attorney general. If the PACC had prosecuting power, it could discourage public officials from “seeking to break anti-corruption law” because there would be a greater chance of them facing prosecution.

One officer said, “I believe, in a country where both the public prosecution office and an [anti-corruption agency] can exercise prosecution power, officers will be more inclined not to infringe anti-corruption law as string-pulling is difficult while the chance of being punished is high.”

Increasing legal initiatives against corruption will help to combat trafficking in Thailand. Other initiatives can help prevent people from entering trafficking in the first place, though, like creating more economic opportunities for vulnerable individuals.

Protestors demonstrate against police and government corruption in Bangkok in 2021 | Photo by Jack Taylor/AFP via Getty Images

Protestors demonstrate against police and government corruption in Bangkok in 2021 | Photo by Jack Taylor/AFP via Getty Images

Economic Solutions

Multiple experts and volunteers on the ground said one of the factors that keeps victims of human trafficking in trafficking is that they don’t have many other options to gain income to support their families.

“It’s also important to understand that the fact that there might not be a lot of opportunities for economic gain, or for a viable way of life, is part of what can fuel trafficking,” Stearns Lawson said.

One way to keep survivors out of trafficking is to offer alternative livelihood options. Fields like agriculture and crafts can offer sustainable income for people in their own communities.

“There’s a fair market for, really responsibly sourced products that are produced by survivors of trafficking,” Stearns Lawson said.

For example, a clothing program in Nepal called Elegantees hires women who are survivors of sex trafficking to make clothing. The website says, “Our dignified jobs provide fair wages and restoration.”

Friedman emphasized the importance of centering the community on these decisions and focusing on what they need.

“As long as you’re listening to people who have been through this about how best to get past it, you’re going to have a good structure for how to get past it,” Friedman said.

Solutions in the Private Sector

It is also important for governments to collaborate with companies on anti-trafficking initiatives to build trust and gain access to information. According to a USAID report, it is important to establish “ongoing communication between the organization and private sector partners.”

Human rights abuses are especially prevalent in the fishing sector. The U.S. Department of Labor’s FAIR Fish project, which ran from 2019 to 2024, developed a “responsible recruitment online course” in Southeast Asian languages and a mobile application for migrant workers that emphasizes the risks of forced labor.

Private sector engagement in anti-trafficking initiatives is crucial, and governments will have to engage with the private sector through programs and laws.

Barrels of fish sit on a dock after being unloaded from a boat | Photo by Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

Barrels of fish sit on a dock after being unloaded from a boat | Photo by Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

Authors

Special Thanks:

Story: Mark Donaldson

Video: Michael Kohler

Audio: Marla Hiller

Data: Jaehyun Han

Editorial: Sarah B. Grace