Advancing U.S. Nearshoring Priorities in Central America with Special Economic Zones

By: Ryan C. Berg & Henry Ziemer

I. Introduction

Why is nearshoring important?

The Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s devastating war in Ukraine have snarled supply chains and disrupted the global economy in unprecedented ways. The era of focusing on minimizing production costs and maximizing economic efficiency instead of geopolitical risk has likely ended.

With the global economy shaped once again by conflict and the return of great power rivalry, U.S. policymakers and business leaders have begun focusing on how to diversify supply chains.

This trend aims to pull Asia-based supply chains away from China and “nearshore” them to the Americas in the name of greater economic security.

One of the primary means to do this is through special economic zones (SEZs) in Latin America and the Caribbean. In Honduras specifically, companies should look to the Zones for Employment and Economic Development (ZEDEs).

By permitting greater amounts of local autonomy, SEZs in particular can provide spaces for institutions, respect for rule of law, and intellectual property rights to realize the value proposition of nearshoring. Furthermore, in the Americas, these zones stand to benefit greatly under the auspices of various regional frameworks for trade, such as the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR).

Nearshoring has drawn high-level attention, with legislation before the U.S. Congress aimed at advancing the trend.

Mexico and Central America in particular are at the forefront of the nearshoring push, with billions of dollars in economic gains on the line for all countries involved.

Key Definitions:

Special Economic Zone – SEZ

A geographically defined area of a country that is designated for a different set of economic regulations than other regions within the same country. SEZs tend to be geared toward attracting economic activity and foreign direct investment.

Zone for Employment and Economic Development –ZEDE

A specific type of SEZ in Honduras that stand out for the level of autonomy given to zone administrators. They were adopted in 2013 as an amendment to the Honduran constitution, allowing the zones to act as special subdivisions of Honduras.

II. The China Challenge

How does U.S.-China competition play out in nearshoring?

In recent years, China has worked assiduously to consolidate its own SEZs throughout the Western Hemisphere, as well as increase its economic influence more generally to fulfill its geopolitical ambitions.

China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has expanded rapidly in Latin America, with 21 countries signing on to the agreement since the end of 2017.

Through the BRI, China has been able to significantly exert soft power in the region through the funding and construction of large-scale infrastructure projects, such as a $1.5 billion contract to build a new bridge over the Panama Canal.

Economic incentives like the BRI have become one of the main tools for China to gain political concessions on issues of major geopolitical importance to the country.

Persuading Latin American countries to withdraw their recognition of Taiwan is one of China’s most pressing objectives.

Out of the 14 countries around the world that still recognize Taiwan, 8 of them are located in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Beijing is pushing hard to reduce this number through a combination of economic incentives and other gifts.

When a country changes from allying with the United States to allying with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), it opens the door for a rapid expansion of PRC influence.

Chinese investment often manifests with nontransparent memorandums of understanding that open the local market to Chinese companies and opportunities for deals between politically connected business elites.

China is known for generating remarkable success from its SEZs. However, Beijing appears to have little appetite for replicating abroad the elements that made its own zones successful—high levels of autonomy and openness to a wide array of foreign businesses.

Indeed, around the world, Chinese initiatives tend to under-employ locals and often generate unmanageable levels of debt.

Should the Chinese model dominate the Americas, it is likely that a far more hostile environment will await international private enterprise in the region.

One example that combines all these issues is El Salvador, where China has been attempting to use its own concept of SEZs to advance its geopolitical and economic interests.

El Salvador switched its relations from Taiwan to the PRC in August 2018. Months before the flip, El Salvador’s then president Salvador Sánchez Cerén announced the creation of a group of SEZs around La Unión, where it later emerged that PRC-based investors were interested in building a port.

Worse, the territory was a political stronghold of Sánchez Cerén’s FMLN party. As such, the move implied that the FMLN’s privileging of Chinese access to the area would be repaid by investments that would benefit the incumbent president’s party in upcoming elections.

Moreover, the land proposed for the zone comprised a massive 14 percent of the country’s territory and nearly half of its coastline.

While this particular zone floundered amid staunch domestic opposition and U.S. pressure, the proposal continues to surface in PRC investment plans for El Salvador.

This potential SEZ featured a number of troubling economic characteristics, mainly those that uniquely benefited China-based investors. Tax-paying companies based in El Salvador would have been prohibited from buying into the SEZ, sidelining many U.S. and European companies and leaving the zone wide open for Chinese state-owned enterprises.

The proposed Chinese SEZ in El Salvador would also bar U.S. and European construction, telecommunications, tourism, and shipping companies from attempting to operate within its borders.

Honduras could suffer a similar fate if it ever decides to recognize China. For now, it is one of the last countries in Central America that maintains diplomatic recognition of Taiwan.

Yet Honduras's position vis-à-vis Taiwan has been imperiled by President Xiomara Castro's campaign promise to switch relations from Taiwan to China for economic purposes after assuming the presidency in January 2022.

Countries like El Salvador that move toward implementing Chinese SEZ projects are not blind to the downsides, but often cite the lack of a credible counteroffer from the United States as part of what pushes them toward China.

A comprehensive, U.S.-led nearshoring strategy may be able to deliver the influx of capital needed to present a credible, Western-led alternative. This is particularly urgent for countries like Honduras that, for now, still ally with Taiwan.

III. Central America's Solutions

What has the United States done to nearshore so far?

Nearshoring is a critical component of the U.S. effort to counter Chinese influence in the Western Hemisphere.

With geopolitical considerations front and center, supply chains and the global investment landscape are likely to become less global and more regional.

Accordingly, SEZs throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, and ZEDEs in Honduras specifically, can advance three of the Biden administration’s top priorities:

1. Improving macroeconomic conditions in the region

2. Reducing irregular migration to the United States

3. Countering China

Unfortunately, Central America’s macroeconomic environment currently leaves much to be desired. Supply chain relocation cannot happen without inviting macroeconomic environments.

Investors and governments must therefore seek out geographically defined areas where rule of law, anti-corruption measures, and regulatory stability and predictability characterize the landscape.

Mexico, which for many appears the natural starting point for nearshoring, has unfortunately been riven by a series of economic and political disruptions, leaving many countries searching for alternative (more reliable) partners in Central America.

Companies shifting operations to Honduran ZEDEs would have the advantage of working inside an SEZ with lower labor costs than in neighboring Mexico.

Greater regulatory flexibility and legal stability guarantees in a ZEDE allow the zone operator to tailor their operational offerings to attract key industries, for example hospitality, medical diagnostics, and fintech.

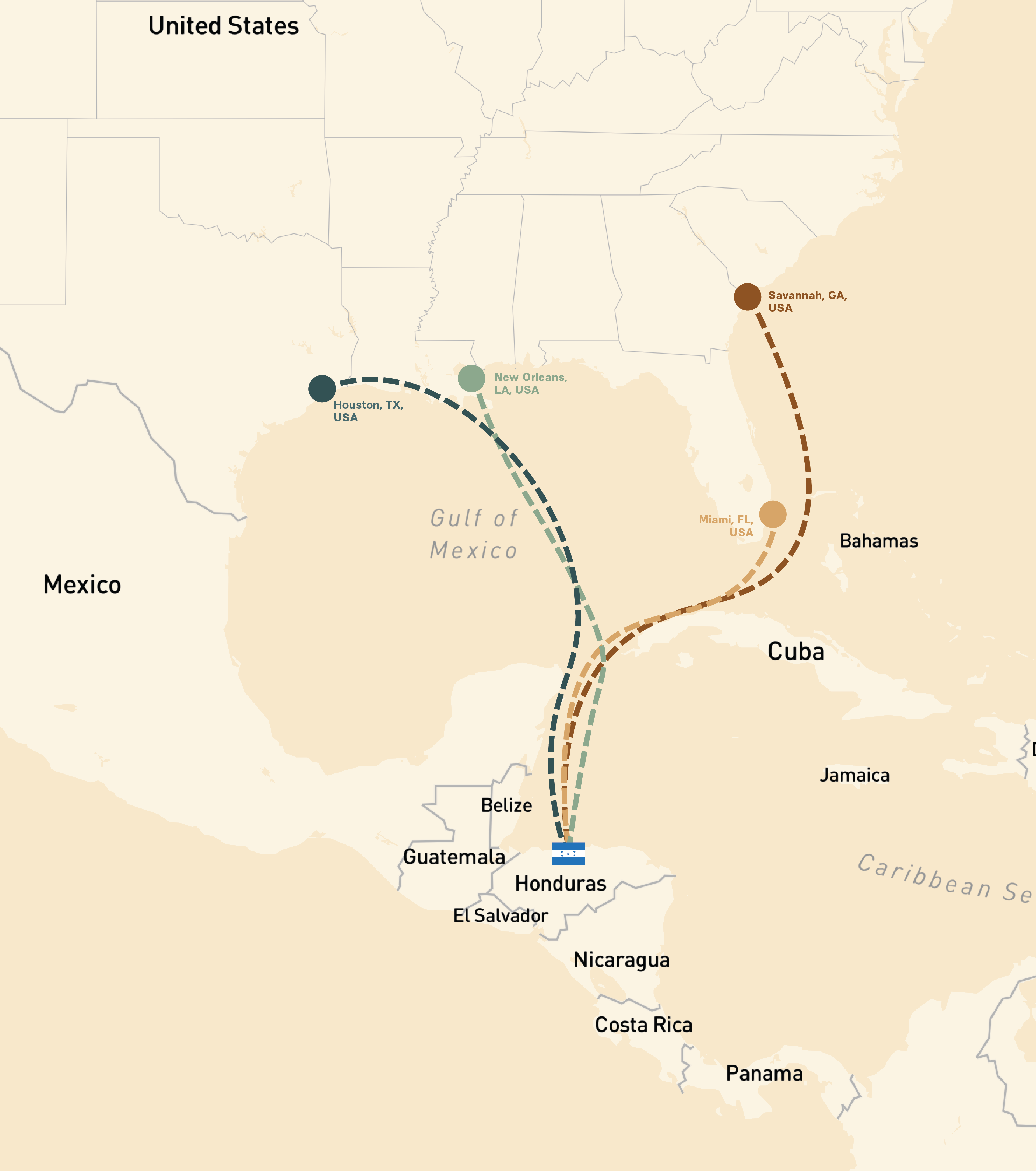

From a geographic standpoint, the Northern Triangle of Central America, especially the Caribbean side, possesses similar advantages as Mexico given its proximity to the United States. Final goods would not have to be shipped long distances to be sold, and the connection between regional ports and the Gulf Coast of the United States would facilitate greater trade.

IV. Next Steps

What Next?

Economic reforms are necessary in many countries in the Northern Triangle.

While this process is often protracted and highly political, SEZs can go a long way to create enabling environments for nearshoring to take place in the immediate term. This is due to their strong property rights regimes, regulatory stability, low taxes, and transparency.

Indeed, without economic growth in Northern Triangle, and the job generation that comes with it, the Biden administration has little chance of successfully implementing its “root causes” strategy to curtail migration.

The dire situation at the U.S. southern border elevates the urgency of generating jobs in Central America.

In Honduras for instance, a youth bulge means that 42 percent of the country is under the age of 20.

This is an especially problematic statistic for stemming migration flows, given that young people are highly mobile and likely to migrate if enduring economic opportunities do not materialize soon.

Lacking strong economic prospects, Hondurans will be forced to seek work in the informal sector or seek employment abroad.

This increases the pressure on policymakers to create better paying jobs.

The exigencies of economic growth and job creation can lead countries to sign unfavorable and often opaque deals with China.

Greater consideration of various types of SEZs would give the Biden administration more appreciation of the level of transparency these zones encourage in their dealings.

After all, opacity only helps to create opportunities for China and other nondemocratic competitors. Anti-corruption efforts have also been the crux of the Biden administration’s approach to Central America.

In contrast to China’s model of opaque, anticompetitive SEZs, the Honduran ZEDEs show promise as a counteroffer for delivering economic growth in a manner aligned with U.S. development (and geopolitical) objectives.

Furthermore, the zones introduce regulatory flexibility and legal stability guarantees, creating business-enabling environments and granting the countries where they operate a competitive edge to court nearshoring opportunities.

Finally, ZEDEs can play a role in shoring up Taiwan’s position in the hemisphere, as they offer countries more transparent and competitive paths to growth that deny Beijing its traditional sources of economic diplomacy.

IV. Next Steps

Conclusion

Washington appears to be waking up to the need for policy action in support of nearshoring.

In February 2021, President Biden ordered a review of U.S. supply chain dependency in key industries such as defense and pharmaceuticals. The findings of that review have galvanized efforts to move supply chains into the Western Hemisphere.

If these policies are to take hold and meet with success, it is most likely that companies will look to duplicate and create shorter, regionally based supply chains.

Building largely on the existing architecture of U.S. trade deals in the region, the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity (APEP) announced at the Summit of the Americas in June emphasizes the need to make U.S. supply chains more resilient to external shocks.

The White House statement highlights the “importance of diversifying and rebalancing our supply chains to minimize disruption risks.”

Fulfilling this goal and ensuring it dovetails with efforts to curb migration requires a heavy focus on the Northern Triangle countries of Central America.

The United States needs to make major follow-up efforts to ensure the goals of the APEP become reality, and SEZs should be part of those efforts. Current legislation before Congress, such as the Western Hemisphere Nearshoring Act, can advance these goals but face long time horizons, risking a loss of momentum and opportunities.

To achieve meaningful supply chain reorientation in any reasonable timeframe, U.S. investors and the Biden administration must look to SEZs in general and ZEDEs in particular to surmount challenging macroeconomic environments in the Northern Triangle.

Rising geopolitical tensions only add to the urgency of this effort.

Simply put, there can be no credible counter to China’s burgeoning economic influence in Latin America without nearshoring, and nearshoring is highly unlikely without the inviting macroeconomic environment characterized by SEZs.

While much remains to be done and supply chain reorientation is a notoriously difficult thing to achieve, nearshoring is both the opportunity of a generation for much of Central America and could pay dividends for generations to come in terms of U.S. security and prosperity in great power competition with China.

This report was made possible through generous support from NeWay Capital LLC.

Authors

Ryan C. Berg, Director, Americas Program

Henry Ziemer, Program Coordinator and Research Assistant, Americas Program

Story Production

- Production by Leena Marte and Claire Smrt, External Relations.

- Project management by Claire Smrt, External Relations.

- Design by Leena Marte, iDeas Lab.

- Map via Mapbox made by Leena Marte, iDeas Lab.

- Development and data visualizations by Lindsay Urchyk and Mariel de la Garza, iDeas Lab.

- Copyediting support by Katherine Stark, iDeas Lab.

- Project and content oversight by Sarah Grace, iDeas Lab.

Photo and Footage Sources

Title Header:

Puerto Cortes Honduras | Mauricio via Adobe Stock

Introduction:

Aerial view of a container ship loading and unloading in a deep sea port. | Aerocaminua via Storyblocks

The China Challenge:

- Las Americas Bridge in Panama City, Panama. | Dualstock via Storyblocks

- China's President Xi Jinping and El Salvador's President Salvador Sanchez Ceren during a welcome ceremony in Beijing in 2018. | Wang Zhao/AFP via Getty Images

- Aerial view of a pier in El Salvador. | Daniel Umana via Adobe Stock

- The national flag of Honduras is seen on containers. | Виталий Соваvia via Adobe Stock

Central America's Solutions:

- Manufacturing line at a factory. | Storyblocks

- Cranes at a Construction Site. | RuckZack via Storyblocks

Next Steps:

- Aerial view of the Mexico-U.S. border wall. | Stockyardph via Adobe Stock

- A Chinese flag waves in Beijing. | Mykola via Adobe Stock

Conclusion:

- Representatives and leaders pose at the 9th Summit of the Americas in 2022. | Frederic J. Brown/AFP via Getty Images

- A map of Central America Map. | Porcupen via Adobe Stock

Tugboat ready to push barge loaded with cargo. | Robert via Adobe Stock