TRACKED

Stories at the Intersection of Migration,

Technology, and Human Rights

Hundreds of millions of people cross borders every year. They are fleeing violence, escaping persecution, joining family, and pursuing jobs abroad.

But whether they travel by land, air, or sea, these migrants encounter technologies designed to help governments manage who is coming to or passing through their countries. These technologies collect several types of migrant data.

CSIS explored some of the technologies migrants encounter during their journeys as well as the human rights implications of their use. Analyzing what motivates governments to deploy technology, and how destination countries in Europe and North America influence that decision-making, is critical to understanding the implications of these decisions on migrant rights.

To understand how widespread the use of these technologies is, CSIS has created two realistic yet fictional migrants, Ana and Mariama, who encounter them firsthand on their journeys across Central America and West and North Africa:

Ana is fleeing persecution from the Ortega government in Nicaragua following the crackdown on pro-democracy advocates around the November 2021 presidential elections.

Ana hopes to make her way from Nicaragua through Central America and Mexico to claim asylum in the United States, following in the footsteps of the 164,000 Nicaraguans who arrived at the southern US border in FY 2022.

Mariama is leaving her home in rural Senegal to seek greater economic opportunity and to join her husband in Spain.

Regular income is scarce in parts of Senegal, especially in rural areas, and her husband was able to secure consistent employment after moving to Spain last year. In 2022, over 15,000 migrants arrived in mainland Spain through the West African Atlantic sea route.

These icons will show the type of data collected from Ana and Mariama throughout the course of their journeys.

Biometric, biographic, entry-exit, travel document, geolocation, and aerial data indicators.

Biometric, biographic, entry-exit, travel document, geolocation, and aerial data indicators.

Ana and Mariama’s stories are not based on any single experience.

Instead, they are the synthesis of extensive open-source research and informational interviews on regional migration trends, policies, and technologies with experts from both regions.

Setting Out

Ana begins her journey with a two-hour bus ride from Estelí to Las Manos, Nicaragua. From there, she plans to join other migrants convening at a caravan heading north from San Pedro Sula, Honduras.

The beginning of Ana’s journey is likely to go unnoticed by the authorities until she attempts to enter Honduras. Governments are typically focused on arrivals into their countries, but few closely monitor departures, particularly of their own citizens.

While some opposition figures are arbitrarily detained when attempting to leave Nicaragua, Ana crosses the border without incident. Nicaragua is party to the Central America-4 Free Mobility Agreement, which allows free movement for Nicaraguans across the region using only their national ID and without requiring a passport or visa.

A public transport bus rides along the Hugo Chavez Avenue in Managua, Nicaragua in 2020. | Maynor Valenzuela/AFP via Getty Images

A public transport bus rides along the Hugo Chavez Avenue in Managua, Nicaragua in 2020. | Maynor Valenzuela/AFP via Getty Images

At the Honduran border, members of the Honduran National Interinstitutional Force for Security (FUSINA) take photographs and fingerprints of all the passengers on Ana’s bus.

Mariama begins her journey from her hometown of Diouloulou, Senegal.

In preparation, Mariama decided to obtain an Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) biometric identity card, which she believes will help her obtain a work visa in Spain. The card serves as a residency permit, passport, and proof of identity for ECOWAS member state citizens such as Mariama.

The ECOWAS ID system links the card to Mariama’s biographical information and physical characteristics, including her name, gender, date and place of birth, address, height, eye color, fingerprints, and photograph.

In 2016, Senegal became the first country in West Africa to adopt ECOWAS biometric ID cards, with support from the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF), which provides funding, equipment, and training to support border management and security projects in the region. Funding from the EUTF also helped develop Senegal’s biometric identity system.

A Senegalese resident's voting card and identity card. | Issouf Sanogo/AFP via Getty Images

A Senegalese resident's voting card and identity card. | Issouf Sanogo/AFP via Getty Images

With her biometric ID card in her bag, Mariama boards a bus to the Gambia. Like Nicaragua, ECOWAS has a freedom of movement protocol allowing citizens to travel without a visa, and she arrives without incident.

Crossing

Borders

From the Nicaragua-Honduras border, Ana makes her way by bus to San Pedro Sula, one of Honduras’s main transit hubs into Guatemala.

She then uses WhatsApp to identify a caravan of Hondurans and Nicaraguans planning to travel north. They head toward Corinto, where they will cross into Guatemala on foot.

At the border, Guatemalan authorities check Ana’s ID, take her photograph, and scan her fingerprints using scanners produced by a U.S. company, Integrated Biometrics.

The U.S. government has provided funding to the Guatemalan government to contract companies such as Integrated Biometrics to develop the country’s biometric infrastructure.

Ana takes a taxi and then a bus from Corinto to Santa Elena. Ana and a group of migrants leave the bus station and travel via caravan to the town of El Ceibo in Guatemala, on the border with Mexico.

A visa is required for her to enter Mexico. Ana attempts to secure a transit visa and fails, so she is turned away at the border. While processing her, however, Mexican immigration officials scan her fingerprints and passport using technology provided by the U.S. State Department’s Document Verification for Travelers program.

This program was funded under the Mérida Initiative, which allocated $3.4 million to promote operational and technological collaboration between U.S. and Mexican customs and border control agencies.

In December 2008, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice speaks during a press briefing about a meeting of the Merida Initiative High-Level Consultative Group to discuss the war on drugs. | Brendan Smialowski/Getty Images

In December 2008, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice speaks during a press briefing about a meeting of the Merida Initiative High-Level Consultative Group to discuss the war on drugs. | Brendan Smialowski/Getty Images

This program officially ended in January 2021 and was replaced by the Bicentennial Framework, which includes the shared objective to “prevent transborder crime,” though no detailed text of the agreement has been released.

After being scanned, Ana’s passport and biometric information are stored in Mexico’s nationwide database, where it can be located or flagged by the Instituto Nacional de Migración (National Migration Institute).

When the authorities release her, Ana starts thinking of other ways to continue her journey north.

Mariama’s bus stops just over the Gambia’s southern border with Senegal, outside the town of Jiboro. She disembarks and inserts her new ECOWAS ID into a scanner developed by the Belgian company Semlex.

Mariama’s biometric data is instantaneously entered into the Gambian national database and the International Organization for Migration’s Migration Information and Data Analysis System (MIDAS).

MIDAS automatically captures travel document images along with Mariama’s biographic and biometric data and information on the bus she arrived on. It allows border authorities to check each traveler’s information against national and Interpol databases.

Mariama takes another bus across the Gambia and back into Senegal. Glancing at her ECOWAS ID, the Senegalese border agent waves her through without scanning it.

Mariama arrives in Dakar, where she stays with a cousin while applying for her Spanish visa.

The coastline of Dakar, Senegal in 2020. | John Wessels/AFP via Getty Images

The coastline of Dakar, Senegal in 2020. | John Wessels/AFP via Getty Images

She pays a third-party company to secure an appointment for her at the Spanish embassy. Before the appointment, she must submit her fingerprints and important documents, such as her birth and marriage certificates, to BLS International, the private company that manages the visa process for Spain in Senegal.

Two weeks after the appointment, Mariama receives an email notification that her visa has been denied. Disappointed but resolved, Mariama starts researching other options to join her husband in Spain.

From Regular

to Irregular Pathways

After being turned away at Mexico’s El Ceibo border crossing, Ana finds her way across the border at an unmanned crossing point further south. However, Ana does not cross unobserved.

Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Migración has launched additional measures to attempt to restrict crossings at its southern border, including using drones and night vision goggles to monitor unmanned crossing points.

Despite these measures, Ana arrives in Tenosique, Mexico, after a full day of walking.

Migrants walk in Tenosique, Tabasco State, Mexico in 2015. | Alfredo Estrella/AFP via Getty Images

Migrants walk in Tenosique, Tabasco State, Mexico in 2015. | Alfredo Estrella/AFP via Getty Images

Mariama’s networks connect her on WhatsApp to a Mauritanian smuggler who offers to help her continue her journey. He sells her a seat on a pirogue, a wooden, canoe-like boat that will travel the Atlantic sea route to Spain’s Canary Islands.

Workers build a pirogue boat in Senegal. | Georges Gobet/AFP via Getty Images

Workers build a pirogue boat in Senegal. | Georges Gobet/AFP via Getty Images

To get to Mauritania, Mariama travels north from Dakar by bus to Diama, Senegal, on the Mauritanian border. Her ECOWAS ID is viewed on both sides of the border but not scanned. She crosses without incident and continues by bus to a coastal village just south of Mauritania’s capital, Nouakchott.

Mariama pays the smuggler almost $1,000 and is taken to a small house where she waits with other aspiring migrants for the pirogue to fill with passengers.

Mariama notices that one of the smugglers has a satellite phone, presumably because of limited cell service on the sea journey. While the phone could be used to call for help in an emergency, the geolocation data could also be used by the Spanish coast guard and Frontex border authorities, the European Union’s border and coast guard agency, to intercept the boat and force its return.

Mariama’s pirogue to the Canary Islands—an autonomous part of Spain—departs Mauritania without incident and travels for two days as planned. However, a storm causes its primary and backup motors to fail and destroys much of their food supplies. The group is set adrift, with inadequate food and water to support a group that far exceeds the ship’s safe capacity limit.

After several days, a joint Spanish-Senegalese naval patrol spots the pirogue via a surveillance drone. Mariama and the other survivors are rescued.

Before departing, the pirogue captain had advised Mariama to destroy her identity documents to make her unidentifiable and thus prevent her deportation if they are intercepted.

Detention and

Return

In Tenosique, Ana is forced to sleep in a makeshift migrant shelter in a local park. The shelter is overcrowded and conditions are poor.

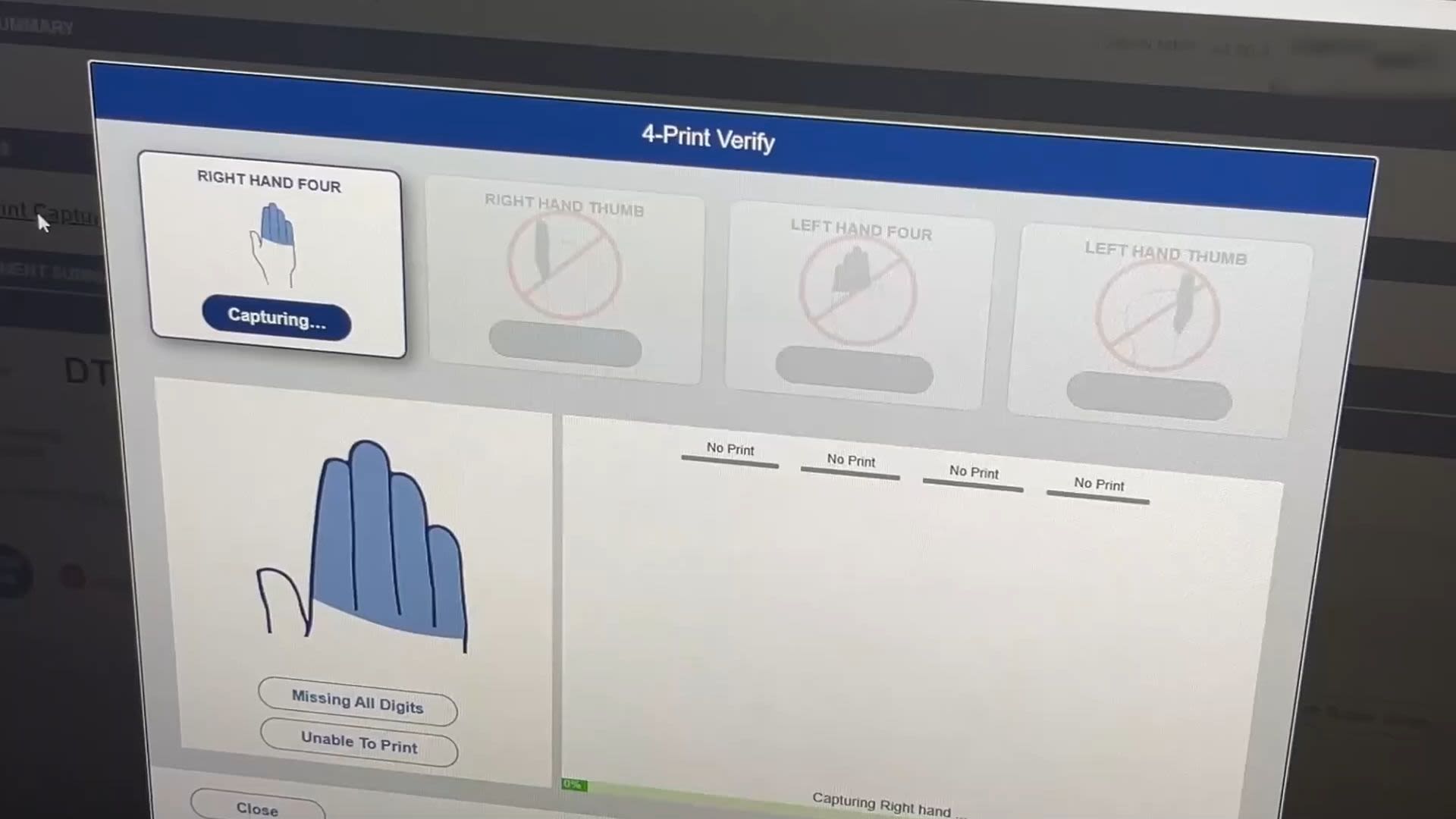

Mexican police and agents of the Instituto Nacional de Migración raid the makeshift camp looking for unauthorized migrants, and Ana is detained for not having documentation authorizing her to be in Mexico. She is sent to a nearby detention center and processed using a biometric kiosk provided through the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Biometric Identification Transnational Migration Alert Program (BITMAP).

Aerial view of the Siglo XXI immigrant detention centre in Tapachula, Mexico in 2019. | Pedro Pardo/AFP via Getty Images

Aerial view of the Siglo XXI immigrant detention centre in Tapachula, Mexico in 2019. | Pedro Pardo/AFP via Getty Images

This is one of 52 detention centers across Mexico outfitted with these biometric kiosks funded by the U.S. State Department under Mexico’s 2014–15 Programa Frontera Sur (Southern Border Plan). Collected data syncs with the Department of Homeland Security’s Automated Biometric Identification System (IDENT), developed by French technology company Thales.

As of September 2021, IDENT stored about 3.2 billion fingerprint images, 6.7 million iris pairs, and approximately 1.1 billion face images, totaling more than 270 million unique identities of migrations from dozens of countries entering, or attempting to enter, the United States.

After a week in detention, Ana is allowed to sign voluntary return documents.

She agrees to return to Nicaragua instead of risking remaining in detention for an extended period and is sent back on a flight to Managua from Mexico City.

After being rescued, Mariama and the surviving passengers are taken to a detention center in Tenerife, in the Canary Islands, where the Spanish Red Cross provides the migrants with medical assistance.

A member of the Spanish Red Cross takes a temperature scan of one of the sub-Saharan migrants on arrival at the Port of Motril after being rescued. | Jesus Merida/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

A member of the Spanish Red Cross takes a temperature scan of one of the sub-Saharan migrants on arrival at the Port of Motril after being rescued. | Jesus Merida/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Mariama tells the Spanish authorities she wishes to seek asylum. Spanish immigration officials ask Mariama for her identity documents, which she no longer has.

However, Mariama’s fingerprint scans are taken using Automated Fingerprint Identification Systems (AFIS) technology. Spanish authorities use this data to access her denied visa request in Senegal and the MIDAS data collected in the Gambia.

Her asylum claim is rejected. Once she is healthy enough to travel, Mariama is deported back to Senegal.

Journey's

End

After returning to Nicaragua, Ana manages to borrow, save, and receive enough money from relatives abroad to hire a smuggler to help her journey north through Central America again.

Reaching the Guatemalan border is relatively easy, given that Ana can travel freely between borders.

From the Guatemalan town of Ciudad Tecún Umán, Ana hires a raftsman to take her across the Suchiate River into Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico and then takes a bus to Tapachula.

Migrants and residents use a makeshift raft to cross the Suchiate river, a natural border between Mexico and Guatemala, in Chiapas state, Mexico in 2018. | Pedro Pardo/AFP via Getty Images

Migrants and residents use a makeshift raft to cross the Suchiate river, a natural border between Mexico and Guatemala, in Chiapas state, Mexico in 2018. | Pedro Pardo/AFP via Getty Images

Ana convenes with a smuggler who is part of a cartel operating in Mexico and who will take her along more dangerous, clandestine routes to reach the United States.

For several days, Ana travels at night on private cargo trucks, sleeping in stash houses the cartel manages. The smuggler transports Ana from Tapachula up north to Reynosa, Mexico.

From there, Ana boards a raft to cross the Rio Grande, eventually reaching the U.S. border at the McAllen-Hidalgo International Bridge in Texas.

Because she plans to claim asylum in the United States, Ana presents herself to U.S. officials at an official border crossing rather than trying to evade detection.

As of December 21, 2022, the United States is no longer enforcing Title 42, which would keep asylum seekers like Ana in Mexico until their turn for processing.

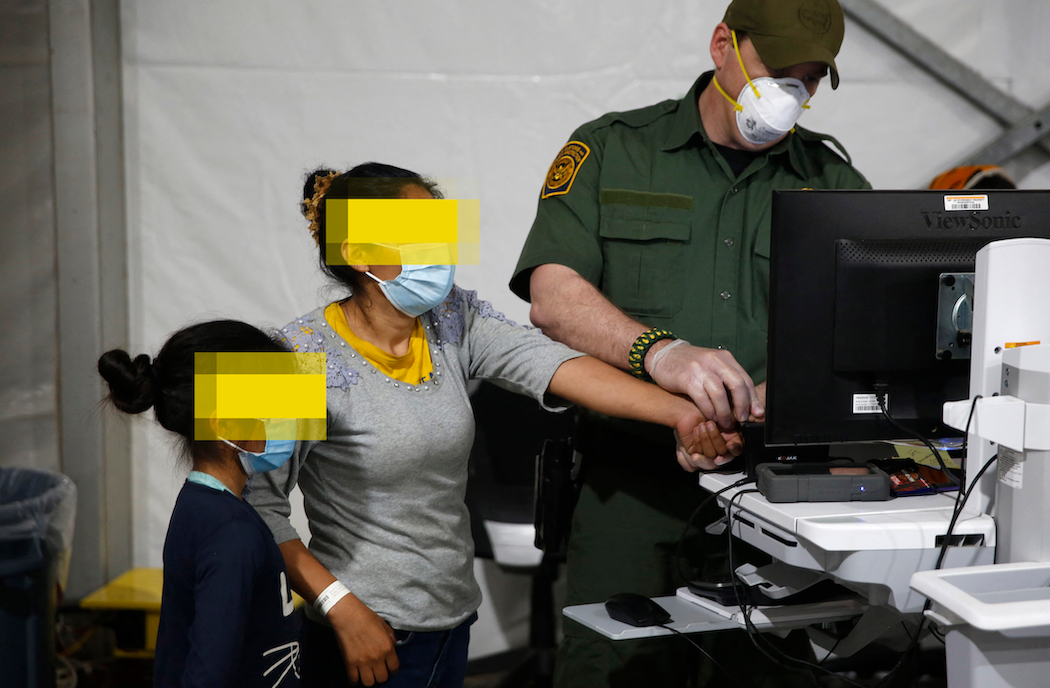

U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers place Ana in the East Hidalgo Detention Center in La Villa, Texas, where about 1,300 other migrants wait for their asylum claims to be processed.

An officer at the Donna, Texas Department of Homeland Security holding facility enters the biometric data of a migrant and her daughter in 2021. | Dario Lopez-Mills/Pool/AFP via Getty Images

An officer at the Donna, Texas Department of Homeland Security holding facility enters the biometric data of a migrant and her daughter in 2021. | Dario Lopez-Mills/Pool/AFP via Getty Images

When she enters the detention center, U.S. immigration authorities quickly find her biographical, biometric, and travel documents within the Department of Homeland Security’s IDENT database. All Ana can do is wait for a credible fear screening with an officer from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to evaluate her asylum claim.

After returning to Senegal, Mariama applies for a replacement ECOWAS ID and borrows enough money from relatives to purchase a one-way plane ticket from Dakar to Casablanca, Morocco.

Dakar's airport employees walk next to a Senegal airlines airbus in Dakar, Senegal. | Seyllou Diallo/AFP via Getty Images

Dakar's airport employees walk next to a Senegal airlines airbus in Dakar, Senegal. | Seyllou Diallo/AFP via Getty Images

At the Dakar airport, Mariama’s travel documents, irises, and fingerprints are scanned at the departure security kiosk. This data collection is part of Senegal’s Système Intégré de Contrôle Migratoire (SICM), provided by U.S. company Securiport LLC.

Upon arrival in Casablanca, Mariama’s ID is scanned by VISOTEC Expert 600 and VISOCORE Inspect devices, provided by the German company Veridos. Veridos-provided facial recognition software and DERMALOG fingerprint scanners collect Mariama’s biometric data.

Since Morocco does not require Senegalese citizens to obtain a visa, she is allowed to enter the country.

In Casablanca, Mariama takes a train north to Tangier and then a bus to Fnideq, Morocco near the border with Ceuta, Spain.

A fence stretches between the Moroccan city of Fnideq and the tiny Spanish enclave of Ceuta. | Fadel Senna/AFP via Getty Images

A fence stretches between the Moroccan city of Fnideq and the tiny Spanish enclave of Ceuta. | Fadel Senna/AFP via Getty Images

She connects via Signal, an encrypted messaging app, with a smuggler promising to deliver her to Ceuta. She pays him the last of her money in exchange for instructions on how to cross the border.

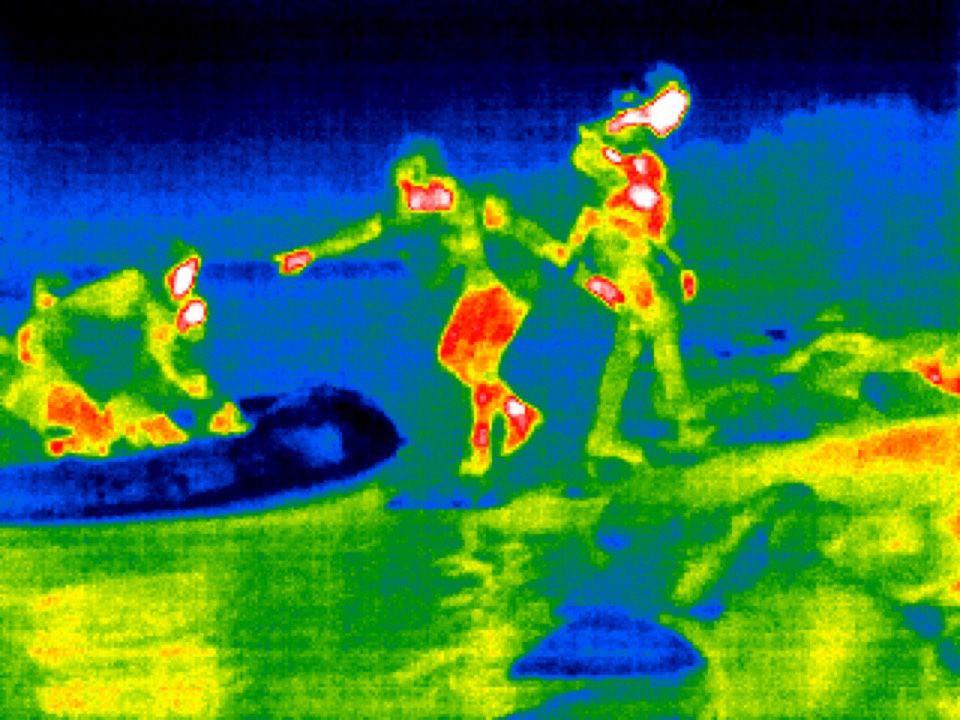

Early the following morning, she approaches a series of border fences. She climbs over three of them undetected, but as she approaches the fourth and final one, she is apprehended by a Spanish border patrol agent who, in cooperation with Moroccan authorities, uses long-range thermal imaging cameras to detect her movement.

People are captured on a thermal imaging camera used by the Spanish Guard Maritime Services in 2015. | Jorge Guerrero/AFP via Getty Images

People are captured on a thermal imaging camera used by the Spanish Guard Maritime Services in 2015. | Jorge Guerrero/AFP via Getty Images

Mariama is taken to a migrant processing center in Ceuta, where her fingerprints are run through the Entry-Exit registration system (EES) created by Thales and Spanish company Zelenza.

Though she finally made it to Spain, her biometrics identify Mariama as a Senegalese citizen.

She is deported home once again.

The rural area of Diouloulou, Senegal, is seen by air. | Licensed from Creatas Video+ via Getty Images

The rural area of Diouloulou, Senegal, is seen by air. | Licensed from Creatas Video+ via Getty Images

Conclusion

Where Does

the Data Go?

Over the course of their journeys, Ana and Mariama interacted with a wide variety of technologies.

Their fingerprints and irises were scanned. Drones, radar, thermal imaging devices, and their cell phones were used to track their movements. Their personal information was collected by governments (and occasionally private companies) along their routes, using technology developed by private companies, and sometimes shared with other governments in the region.

This image made with a thermal camera by U.S. Border Patrol shows migrants attempting to cross the U.S.-Mexico border near the bank of the Rio Grande at night in 2021 in Roma, Texas shortly before they were apprehended. | John Moore/Getty Images

This image made with a thermal camera by U.S. Border Patrol shows migrants attempting to cross the U.S.-Mexico border near the bank of the Rio Grande at night in 2021 in Roma, Texas shortly before they were apprehended. | John Moore/Getty Images

Ana's Data

In Latin America, Ana’s biometric and biographic data is collected when she crosses the borders from Nicaragua to Honduras, when she crosses from Guatemala to Mexico, and when she is detained in Mexico.

In 2019, the United States signed updated agreements with the governments of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador to share biometric information collected from migrants. The goal of this Biometric Data Sharing Program (BDSP) is to enhance cooperation on irregular migrant identification to monitor transnational criminal activities and human smuggling.

However, the system enables the automatic, real-time exchange of biometric and biographical information to monitor everyone crossing the border, not just criminals and smugglers.

Mexico also shares the information it collects with the United States. When Ana is detained in Mexico, the information scanned in the detention center kiosks is shared with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security through BITMAP, which the United States has funded.

The Automated Real-Time Identity Exchange System (ARIES) facilitates data exchange between BITMAP submissions and the Department of Homeland Security’s IDENT system. IDENT is the agency-wide system used to store and process biometric and biographical data on people entering the United States and those crossing borders in foreign countries with whom the United States has information-sharing agreements and arrangements.

As a result, when Ana arrives in the United States and is taken into custody, her biometric and biographic information has already beat her to the border.

Mariama's Data

In West and North Africa, Mariama’s information is collected when she crosses from Senegal into the Gambia and again when she enters Mauritania. Spanish authorities collect it when she applies for a visa and again when she is rescued at sea, and Senegalese and Moroccan authorities again capture it when she flies from Dakar to Casablanca.

As a result of data-sharing arrangements between the European Union and West and North African governments—such as the Seahorse Network, which includes Senegal, Mauritania, and Morocco—by the time Mariama is picked up by Spanish authorities in Ceuta, her biographic and biometric information is also already available to Spanish authorities.

Migrants such as Ana and Mariama are routinely required to share their personal information without knowing or giving informed consent as to how it is being used, where it is stored, with whom it is being shared, or what safeguards are in place.

These practices can infringe on migrants’ privacy rights and can blur the lines between migration management, border security, and law enforcement.

Governments have a right to implement safe, orderly, and regular migration systems. Special care should be taken to ensure that exercising that right does not come at the expense of migrants’ human rights.

This report is supported by a grant from the Open Society Foundations.

WRITTEN BY

Special thanks to Abigail Edwards, research intern with the CSIS Project on Fragility and Mobility, and Sophia Swanson, research intern with the CSIS Human Rights Initiative.

PRODUCTION BY

- Story editing, production, and design by Sarah Grace, iDeas Lab

- Mapping and design assistance by Michael Kohler, iDeas Lab

- Copyediting support by Katherine Stark, iDeas Lab

PHOTO AND FOOTAGE CREDITS

Title Header: A woman wears a face mask on a bus in Managua, Nicaragua in 2020. Licensed from Inti Ocon/AFP via Getty Images.

Setting Out: Aerial footage shows the backwaters around Diouloulou, Senegal. Licensed from Creatas Video+ via Getty Images.

Crossing Borders: A packed bus travels across Nicaragua in 2016. Licensed from Josep Gutierrez/Camera Crew Barcelona via Getty Images.

From Regular to Irregular Pathways: :A beach in Mauritania teems with pirogue boats. Licensed from Adobe Stock.

Detention and Return: A pilot with U.S. Customs and Border Protection remotely flies a MQ-9 Reaper/Predator drone over the U.S.-Mexico border at Fort Huachuca, Arizona to intercept immigrants crossing illegally from Mexico in 2022. Licensed from John Moore/Getty Images.

Journey's End: A computer saves fingerprints scanned from a migrant at a processing center in El Paso, Texas. Licensed from Creatas Video+ via Getty Images.

Conclusion: Shelves of processors are seen in a data processing center in an undisclosed location. Licensed from Storyblocks.